use. With this fact before us, we shall do well to pause, before we consign even the most glaring pedantries of our forefathers to oblivion.

[ W. S. R. ]

REDEKER, Louise dorette Auguste, a contralto singer, who made her first appearance in London at the Philharmonic Concert of June 19, 1876, and remained a great favourite until she retired from public life on her marriage, Oct. 19, 1879. She was born at Duingen, Hanover, Jan. 19, 1853, and from 1870 to 73 studied in the Conservatorium at Leipzig, chiefly under Konewka. She sang first in public at Bremen in 1873. In 1874 she made the first of several appearances at the Gewandhaus, and was much in request for concerts and oratorios in Germany and other countries during 74 and 75. In England she sang at all the principal concerts, and at the same time maintained her connexion with the Continent, where she was always well received. Her voice is rich and sympathetic; she sings without effort and with great taste.

[ G. ]

REDFORD, John, was organist and almoner, and master of the Choristers of St. Paul's Cathedral in the latter part of the reign of Henry VIII (1491–1547). Tusser, the author of the 'Hundred good points of Husbandrie' was one of his pupils. An anthem, 'Rejoice in the Lorde alway,' printed in the appendix to Hawkins's History and in the Motett Society's first volume, is remarkable for its melody and expression. Some anthems and organ pieces by him are in the MS. volume collected by Thomas Mulliner, master of St. Paul's School, afterwards in the libraries of John Stafford Smith and Dr. Rimbault, and now in the British Museum. A motet, some fancies and a voluntary by him are in MS. at Christ Church, Oxford. His name is included by Morley in the list of those whose works he consulted for his 'Introduction.'

[ W. H. H. ]

REDOUTE. Public assemblies at which the guests appeared with or without masks at pleasure. The word is French, and is explained by Voltaire and Littré as being derived from the Italian ridotto—perhaps with some analogy to the word 'resort.' The building used for the purpose in Vienna, erected in 1748, and rebuilt in stone in 1754, forms part of the Burg or Imperial Palace, the side of the oblong facing the Josephs-Platz. There was a grosse and a kleine Redoutensaal. In the latter Beethoven played a concerto of his own at a concert of Haydn's, Dec. 18, 1795. The rooms were used for concerts till within the last ten years. The masked balls were held there during the Carnival, from Twelfth Night to Shrove Tuesday, and occasionally in the weeks preceding Advent; some being public, i.e. open to all on payment of an entrance fee, and others private. Special nights were reserved for the court and the nobility. The 'Redoutentänze'—Minuets, Allemandes, Contredanses, Schottisches, Anglaises, and Ländler—were composed for full orchestra, and published (mostly by Artaria) for pianoforte. [1]Mozart, Haydn, [2]Beethoven, Hummel, Woelfl, Gyrowetz, and others, have left dances written for this purpose. Under the Italian form of Ridotto, the term was much employed in England in the last century.

[ C. F. P. ]

REDOWA, a Bohemian dance which was introduced into Paris in 1846 or 47, and quickly attained for a short time great popularity, both there and in London, although now seldom danced. In Bohemia there are two variations of the dance, the Rejdovák, in 3–4 or 3–8 time, which is more like a waltz, and the Rejdovacka, in 2–4 time, which is something like a polka. The following words are usually sung to the dance in Bohemian villages:

Kann nicht frei'n, weil Eltern

Nicht ihr Jawort gaben:

Weil ich kommen könnte,

Wo kein Brot sie haben—

Wo kein Brot sie haben,

Keine Kuchen backen,

Wo kein Heu sie mähen

Und kein Brennholz hacken.

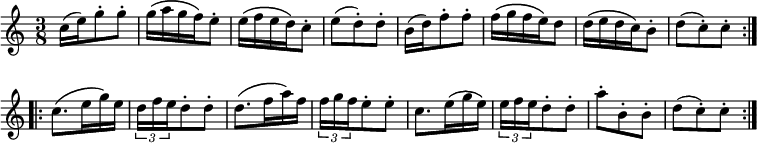

The ordinary Redowa is written in 3–4 time (Maelzel's Metronome ![]() = 160). The dance is something like a Mazurka, with the rhythm less strongly marked. The following example is part of a Rejdovak which is given in Köhler's 'Volkstänze aller Nationen'—

= 160). The dance is something like a Mazurka, with the rhythm less strongly marked. The following example is part of a Rejdovak which is given in Köhler's 'Volkstänze aller Nationen'—

[ W. B. S. ]

REED (Fr. Anche; Ital. Ancia; Germ. Blätt, Rohr). The speaking part of many instruments, both ancient and modern; the name being derived from the material of which it has been immemorially constructed. This is the outer silicious layer of a tall grass, the Arundo Donax or Sativa, growing in the South of Europe. The substance in its rough state is commonly called 'cane,' though differing from real cane in many respects. The chief supply is now obtained from Frejus on the Mediterranean coast. Many other materials, such as lance-wood, ivory, silver, and 'ebonite,' or hardened india-rubber, have been experimentally substituted for the material first named; but hitherto without success. Organ reeds were formerly made of hard wood, more recently of brass, German silver, and steel. The name Reed is, however, applied by organ-builders to the metal tube or channel against which the