received in a campaign against the Huns; but it seems more probable that he was murdered by the soldiers, who were averse from further campaigns against Persia, at the instigation of Arrius Aper, prefect of the praetorian guard. Carus seems to have belied the hopes entertained of him on his accession, and to have developed into a morose and suspicious tyrant.

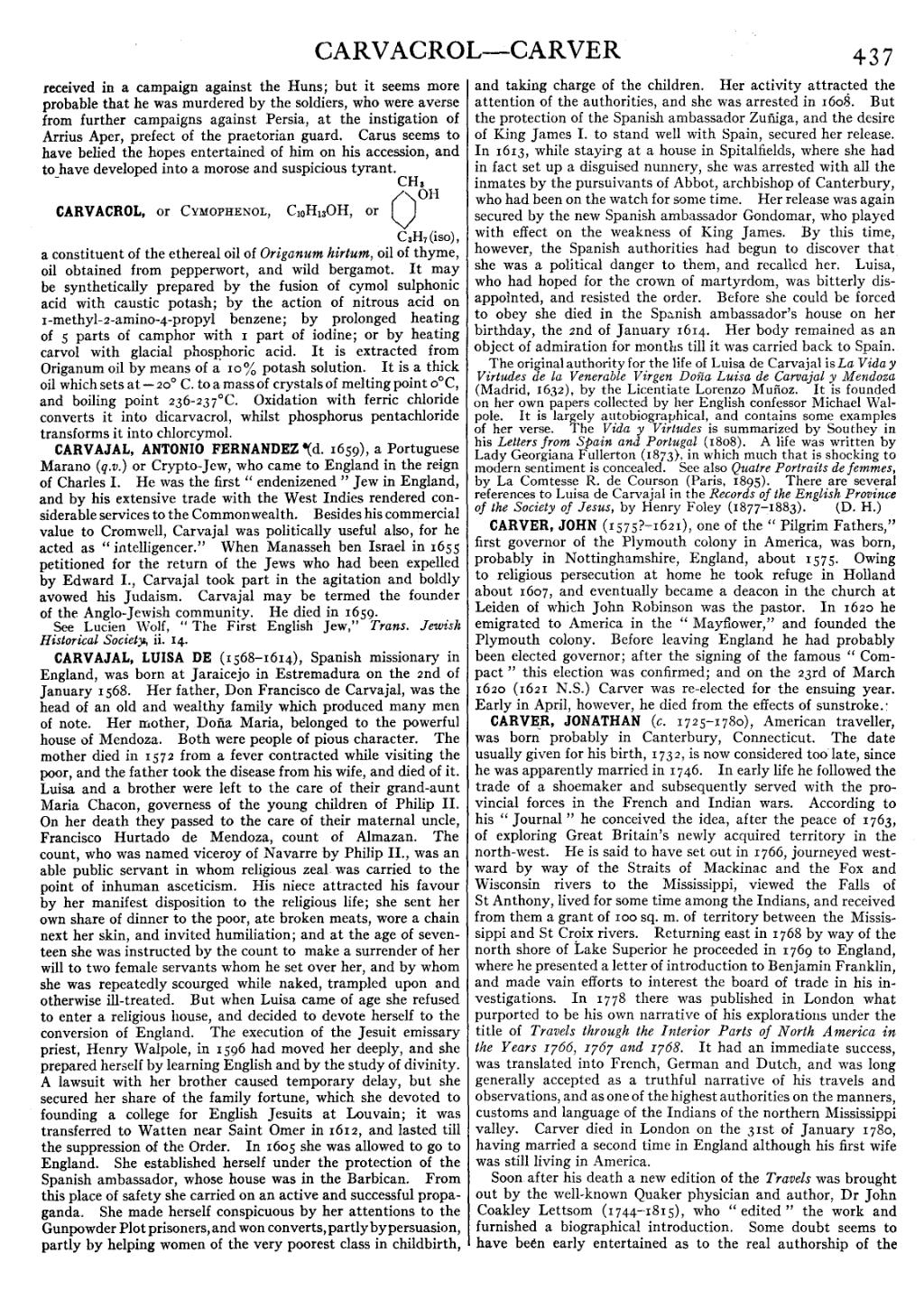

CARVACROL, or Cymophenol, C10H13OH, or  , a constituent of the ethereal oil of Origanum hirtum, oil of thyme, oil obtained from pepperwort, and wild bergamot. It may be synthetically prepared by the fusion of cymol sulphonic acid with caustic potash; by the action of nitrous acid on 1-methyl-2-amino-4-propyl benzene; by prolonged heating of 5 parts of camphor with 1 part of iodine; or by heating carvol with glacial phosphoric acid. It is extracted from Origanum oil by means of a 10% potash solution. It is a thick oil which sets at −20°C. to a mass of crystals of melting point 0°C, and boiling point 236–237°C. Oxidation with ferric chloride converts it into dicarvacrol, whilst phosphorus pentachloride transforms it into chlorcymol.

, a constituent of the ethereal oil of Origanum hirtum, oil of thyme, oil obtained from pepperwort, and wild bergamot. It may be synthetically prepared by the fusion of cymol sulphonic acid with caustic potash; by the action of nitrous acid on 1-methyl-2-amino-4-propyl benzene; by prolonged heating of 5 parts of camphor with 1 part of iodine; or by heating carvol with glacial phosphoric acid. It is extracted from Origanum oil by means of a 10% potash solution. It is a thick oil which sets at −20°C. to a mass of crystals of melting point 0°C, and boiling point 236–237°C. Oxidation with ferric chloride converts it into dicarvacrol, whilst phosphorus pentachloride transforms it into chlorcymol.

CARVAJAL, ANTONIO FERNANDEZ (d. 1659), a Portuguese

Marano (q.v.) or Crypto-Jew, who came to England in the reign of Charles I. He was the first “endenizened” Jew in England, and by his extensive trade with the West Indies rendered considerable services to the Commonwealth. Besides his commercial value to Cromwell, Carvajal was politically useful also, for he acted as “intelligencer.” When Manasseh ben Israel in 1655 petitioned for the return of the Jews who had been expelled by Edward I., Carvajal took part in the agitation and boldly avowed his Judaism. Carvajal may be termed the founder of the Anglo-Jewish community. He died in 1659.

See Lucien Wolf, “The First English Jew,” Trans. Jewish Historical Society, ii. 14.

CARVAJAL, LUISA DE (1568–1614), Spanish missionary in England, was born at Jaraicejo in Estremadura on the 2nd of January 1568. Her father, Don Francisco de Carvajal, was the head of an old and wealthy family which produced many men of note. Her mother, Doña Maria, belonged to the powerful house of Mendoza. Both were people of pious character. The mother died in 1572 from a fever contracted while visiting the poor, and the father took the disease from his wife, and died of it. Luisa and a brother were left to the care of their grand-aunt Maria Chacon, governess of the young children of Philip II. On her death they passed to the care of their maternal uncle, Francisco Hurtado de Mendoza, count of Almazan. The count, who was named viceroy of Navarre by Philip II., was an able public servant in whom religious zeal was carried to the point of inhuman asceticism. His niece attracted his favour by her manifest disposition to the religious life; she sent her own share of dinner to the poor, ate broken meats, wore a chain next her skin, and invited humiliation; and at the age of seventeen she was instructed by the count to make a surrender of her will to two female servants whom he set over her, and by whom she was repeatedly scourged while naked, trampled upon and otherwise ill-treated. But when Luisa came of age she refused to enter a religious house, and decided to devote herself to the conversion of England. The execution of the Jesuit emissary priest, Henry Walpole, in 1596 had moved her deeply, and she prepared herself by learning English and by the study of divinity. A lawsuit with her brother caused temporary delay, but she secured her share of the family fortune, which she devoted to founding a college for English Jesuits at Louvain; it was transferred to Watten near Saint Omer in 1612, and lasted till the suppression of the Order. In 1605 she was allowed to go to England. She established herself under the protection of the Spanish ambassador, whose house was in the Barbican. From this place of safety she carried on an active and successful propaganda. She made herself conspicuous by her attentions to the Gunpowder Plot prisoners, and won converts, partly by persuasion, partly by helping women of the very poorest class in childbirth, and taking charge of the children. Her activity attracted the attention of the authorities, and she was arrested in 1608. But the protection of the Spanish ambassador Zuñiga, and the desire of King James I. to stand well with Spain, secured her release. In 1613, while staying at a house in Spitalfields, where she had in fact set up a disguised nunnery, she was arrested with all the inmates by the pursuivants of Abbot, archbishop of Canterbury, who had been on the watch for some time. Her release was again secured by the new Spanish ambassador Gondomar, who played with effect on the weakness of King James. By this time, however, the Spanish authorities had begun to discover that she was a political danger to them, and recalled her. Luisa, who had hoped for the crown of martyrdom, was bitterly disappointed, and resisted the order. Before she could be forced to obey she died in the Spanish ambassador’s house on her birthday, the 2nd of January 1614. Her body remained as an object of admiration for months till it was carried back to Spain.

The original authority for the life of Luisa de Carvajal is La Vida y Virtudes de la Venerable Virgen Doña Luisa de Carvajal y Mendoza (Madrid, 1632), by the Licentiate Lorenzo Muñoz. It is founded on her own papers collected by her English confessor Michael Walpole. It is largely autobiographical, and contains some examples of her verse. The Vida y Virtudes is summarized by Southey in his Letters from Spain and Portugal (1808). A life was written by Lady Georgiana Fullerton (1873), in which much that is shocking to modern sentiment is concealed. See also Quatre Portraits de femmes, by La Comtesse R. de Courson (Paris, 1895). There are several references to Luisa de Carvajal in the Records of the English Province of the Society of Jesus, by Henry Foley (1877–1883). (D. H.)

CARVER, JOHN (1575?–1621), one of the “Pilgrim Fathers,” first governor of the Plymouth colony in America, was born, probably in Nottinghamshire, England, about 1575. Owing to religious persecution at home he took refuge in Holland about 1607, and eventually became a deacon in the church at Leiden of which John Robinson was the pastor. In 1620 he emigrated to America in the “Mayflower,” and founded the Plymouth colony. Before leaving England he had probably been elected governor; after the signing of the famous “Compact” this election was confirmed; and on the 23rd of March 1620 (1621 N.S.) Carver was re-elected for the ensuing year. Early in April, however, he died from the effects of sunstroke.

CARVER, JONATHAN (c. 1725–1780), American traveller, was born probably in Canterbury, Connecticut. The date usually given for his birth, 1732, is now considered too late, since he was apparently married in 1746. In early life he followed the trade of a shoemaker and subsequently served with the provincial forces in the French and Indian wars. According to his “Journal” he conceived the idea, after the peace of 1763, of exploring Great Britain’s newly acquired territory in the north-west. He is said to have set out in 1766, journeyed westward by way of the Straits of Mackinac and the Fox and Wisconsin rivers to the Mississippi, viewed the Falls of St Anthony, lived for some time among the Indians, and received from them a grant of 100 sq. m. of territory between the Mississippi and St Croix rivers. Returning east in 1768 by way of the north shore of Lake Superior he proceeded in 1769 to England, where he presented a letter of introduction to Benjamin Franklin, and made vain efforts to interest the board of trade in his investigations. In 1778 there was published in London what purported to be his own narrative of his explorations under the title of Travels through the Interior Parts of North America in the Years 1766, 1767 and 1768. It had an immediate success, was translated into French, German and Dutch, and was long generally accepted as a truthful narrative of his travels and observations, and as one of the highest authorities on the manners, customs and language of the Indians of the northern Mississippi valley. Carver died in London on the 31st of January 1780, having married a second time in England although his first wife was still living in America.

Soon after his death a new edition of the Travels was brought out by the well-known Quaker physician and author, Dr John Coakley Lettsom (1744–1815), who “edited” the work and furnished a biographical introduction. Some doubt seems to have been early entertained as to the real authorship of the