Provincial Geographies of India/Volume 4/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II

CLIMATE

As already indicated, a country of such diverse physical features and of such vast extent naturally presents a rich variety of climate. Rangoon and the maritime districts, as well as the plain country up to about the latitude of the northern limit of Henzada, are hot and moist. South of the southern edge of Henzada and Tharrawaddy, the Delta districts and the plains of the Pegu division have a mean annual rainfall of about 100 inches; fairly evenly distributed locally and remarkably consistent, the average being, however, substantially exceeded in Pegu and Hanthawaddy. The sea board districts of Arakan and Tenasserim[1] have torrential rains in even greater abundance. In the last four years[2], the annual average of these districts has exceeded 200 inches, Kyaukpyu alone falling a little short of that figure. The maximum average of those years was 253 inches in Akyab; the highest recorded rainfall in 1920 being at Palaw in Mergui, 279·17 inches. In this wet country, the rains, brought by the south-west monsoon, last approximately from May to October; they have never been known to fail to so dangerous a degree as to threaten the rice crop of Lower Burma. Welcomed at first as a relief after the steamy heat of May, the rains soon become monotonous. By the middle of August, with a rich growth of fungus on one's boots, one begins to tire of them. But it does not always rain day and night. On most days, either the morning or the evening is fine and gives opportunity for exercise. Cyclones are not very frequent visitors. In 1902, early in May, occurred one of great violence which, in Rangoon, unroofed houses and magazines, swept boats high and dry, and blocked most of the roads in the Cantonment with torn branches of trees. Some years later a fierce cyclone ravaged Akyab.

This part of the Province enjoys no really cold season, but from November till the end of January there is a sensible fall of temperature, the thermometer descending

sometimes as low as 6o° F. From February to May, the days are hot and oppressive, but the thermometer seldom rises above 100°. As a rule, the nights are not intolerably warm. In Rangoon, which may be regarded as typical, the average temperature, day and night, in January is nearly 77°, in May, 84°. Further north, the climate changes gradually. Henzada, Tharrawaddy and Toungoo, approaching the dry zone, are almost level with rainfall of about 80 inches. Prome and Thayetmyo drop to not much over 40. These districts are extremely hot in the summer months and have a moderate cool season.

The real dry zone, from the old frontier of Upper Burma to about 60 miles north of Mandalay, has, for the most part, normally, an average annual rainfall of about 30 inches. But from year to year, it varies capriciously. In Pakôkku, the driest district, the yearly total is not much more than 20 inches. Though Shwebo has the highest mean with 38 inches, in 1920 the actual rainfall was under 24. In this tract, in the plains, the soil is dry and bare; in Spring and early Summer, the temperature rises to as high as 115°; and there is good and seasonable cold weather from November to March, the thermometer in the daytime falling to as low as 55°. At Mandalay, the annual rainfall is nearly 32 inches; the average temperature in January 70°, in May 80°. Scanty rainfall at times causes crops to fail on unirrigated lands and has, occasionally, produced conditions of scarcity approaching famine. Although the Summer is distinctly hot and parching there is no such fierce and fervent heat as in the plains of Upper India. The nights are nearly always bearable. And in Mandalay and Yamèthin and other places similarly situated, constant high winds, though tiringly monotonous, are yet welcome as tempering the excessive heat. In the hills of this area the extremes of temperature are 90° and 32°.

North of about the latitude of the Third Defile[3], the rainfall again becomes fairly abundant, rising from some 50 inches in Katha to 69 in Bhamo and 80 in Myitkyina, while the temperature, though hot in Summer, is cool and pleasant in the winter months. In the Kachin and Chin Hills, the heat is never excessive and at times the temperature is very low, the range being between 85° and 25°. In the high lands on the Chinese frontier, east of Bhamo, severe frosts prevail for several weeks, producing solid blocks of ice to the astonishment of the Burman from the plains. In the Chin Hills, the annual rainfall varies from 50 to 110 inches. The Shan plateau enjoys a temperate climate and a consistent rainfall varying from 60 to 80 inches[4].

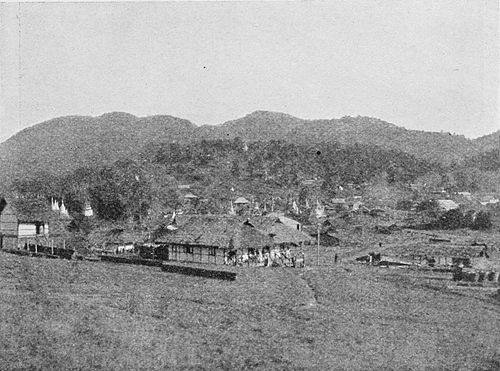

Hill Stations. In most parts of the Province, except the true Delta and the plain country to the east thereof, are to be found in the hills refuges from the severity of the

hot season. Maymyo, on the edge of the Northern Shan States, though on a plateau only 3400 feet above the sea, is yet comparatively cool in the warm months, cold but not too cold in winter, wet but not too wet in the rains. Kalaw, the Mussoorie of Burma, lying among pine-groves on the border of the Myelat, is another popular summer resort. Toungoo has a comfortable hill station at Thandaung and Bhamo the cool and healthy heights of Sinlumgaba. Mt Victoria and Kanpetlet in the Pakôkku Chin Hills, ideal summer resorts, are inaccessible. But Popa in Myingyan offers cool days and nights to dwellers in the parched plains of the central dry zone. Even as far south as Henzada, Allantaung, on a peak of the Arakan Yoma, is cool and refreshing in the hot season. Jaded residents of the Delta find here relief and recreation. A Commis-

sioner's wife, Mrs Maxwell Laurie, has described Allantaung in the columns of the Indiaman:

Burma is usually regarded as an unhealthy country. The mental picture is of a land of dismal swamps and deadly marshes, far different from the glowing reality. The impression of unhealthiness is due to the hardships and privations suffered by troops, police, and civil officers during and after the three Burmese Wars. In unsuitable conditions, much sickness and mortality were inevitable. But on the mind of the visitor in ordinary times, who lived in normal surroundings, the contrary impression was stamped. Writing in 1795, Symes says: "The climate of every part of the Burman Empire which I have visited bore testimony to its salubrity[5]." It is true that his range was limited to Rangoon and the country along the Irrawaddy as far north as Ava. But his record is of interest as indicating his experience in comparatively early times before the dawn of sanitation. On the whole, his impression was accurate. Parts of Burma, such as Northern Arakan, Salween, Katha, and all tracts lying at the foot of hills, are notoriously unhealthy owing to the prevalence of malarial fever. Cholera is never absent throughout a whole year, though serious epidemics are far less frequent than of yore. Plague has not been extirpated by the efforts of seventeen years. But cholera and plague are accidents. With the more rigorous application of improved sanitary methods, these diseases as well as malarial fever should be banished. Subject to these exceptions, the Province, as a whole, is not unhealthy. In particular, the swamps of the Delta and the great rice plains, though enervating, are not deadly. But it must be admitted that, everywhere, vitality once impaired is not readily restored. The annual mortality is about 25 per thousand. But the statistics are not entirely trustworthy. In 1918, owing to the epidemic of influenza, the death of nearly 40 per thousand was recorded.