CHAPTER VIII

THE REASONED EQUITATION

We owe the reasoned equitation largely to Baucher. Before his day, even in ancient times, men had, indeed, an idea of the need of the state of equilibrium on the part of the horse; and they had tried, unsuccessfully, to obtain this by various methods, often complicated, and involving series of movements and also mechanical devices. Baucher not only created a system for obtaining the state of equilibrium; in addition, in his L'Equitation Raisonnée, he set forth the principles on which the whole reasoned equitation is based.

These are in brief:

The state of equilibrium is not the result of any instincts of the horse; but, on the contrary, is imposed upon the horse by the rider, in the form of an increased muscular activity which the rider stimulates.

The horse, compelled to the state of equilibrium by the man, is itself in a state of complete submission, in which it cannot use its brute strength to resist its rider, but can nevertheless execute any natural movement with the least possible waste of energy.

The weight of the man, also in equilibrium upon the horse's back, is borne with the least possible effort, and with an ease for which the animal is manifestly grateful to its master.

Now it is absolutely true that only as the result of training are the enormous powers of the horse brought under the man's intelligence, without violence and without physical or moral pain. The one is wise, the other is strong. The two form a friendly unit in which the brute is submissive and happy. But since the reasoned equitation follows a series of progressive exercises, in which the more advanced rest on those which precede, it is essential that the same rider use always the same horse, during the time necessary to complete its training.

A sound and well-conformed animal, energetic but good-tempered, will be the easiest to train. A full bridle should be employed, with a bit of medium power, a Baucher snaffle, curb chain, and lip strap. The work on foot requires a three-foot whip. Later in the training, when the horse is mounted, spurs will be needed. A well-kept second-hand English saddle is better than a new one.

Since the reasoned equitation has for its purpose to teach the rider both how to train his horse, and also how to ride a horse already trained in the system, it is useful for professional riding-masters and trainers, and for all civilians. But it is only after several years of the usual equitation that either the theory or the practice of the reasoned equitation becomes of any particular benefit. Baucher wrote out his method primarily for cavalry officers and other professionals, and his principles are very complicated for an amateur to follow. I have, however, taught the reasoned equitation to a great number of amateur riders, both men and women. I have, in addition, simplified Baucher's theory and clarified his methods so that now the entire system is practical for amateur and professional alike. Breaking in, for the young horse, involves acquaintance with the trainer, so that it will come to him and follow him without fear or anxiety, accept the bridle without reluctance, stand quietly for mounting and dismounting, walk, trot, and gallop under the rider's weight without nervous tension, turn to either side by the rein, stop and stand still. That these movements should all be done perfectly, is not, however, so important as that the horse should be docile and quiet.

This first portion of a horse's training does not need an experienced master. Any ordinary rider can manage it, provided only that he have perseverance, patience, kindness, love for the animal, and a sufficiently good seat to resist the exuberance of a young horse. For a young horse is like a child, ignorant, timid, anxious; and if the trainer is not indulgent, patient, and fond of the animal, sooner or later a little too much severity, the least touch of brutality, will reënforce this natural timidity, and produce restiveness and bad temper that the horse will never outgrow. Many a horse has been spoiled by unintelligent trainers. For the horse's memory is excellent, and very seldom does it forget harsh treatment. Baucher says, and I am of his opinion, that it needs uncommon discrimination on the part of an owner to pick the right man for breaking in a young horse. Indeed, to judge wisely the time required for the work, the state of progress of the young animal and its muscular development, to reward obedience suitably, and to punish with wise moderation, demand a judgment and an experience that come near to talent.

It is far easier to train a child than to reform a criminal: and it is the same with a young horse. But if the instructor lacks patience or kindness or experience, the child will revolt against his teachers, and the horse against its riders, and both will be permanently harmed. And since the breaking in is the beginning of a horse's education, the man who undertakes it can never have too much of each of these essential qualities.

During the breaking in, a single bridoon should be used, rather than a full bridle. The chain and bit produce too powerful an effect on the mouth of a young horse, and it will not understand. Moreover, they cannot be managed properly during the rearing, kicking, and buck-jumping to which young horses are addicted.

If the horse is nervous or violent, I employ the cavesson with the longe. The horse is saddled and bridled, the stirrups being raised against the saddle by a knot in the straps. The cavesson is put on over the bridle, the throat-latch tight enough to prevent

the cavesson from slipping and hurting the horse's eyes if the animal becomes violent. Around the saddle I buckle a surcingle, with two buckles and a little strap, to hold the reins when not in use, and to prevent their falling down in front of the animal's legs.

I have also two buckles on the headpiece of the cavesson; and two pairs of old reins, with holes at each end, equally spaced. One pair buckles to the cavesson and to the snaffle, the two sides just alike. The other ends of this pair fasten at the surcingle, the two reins of equal length. The second pair of reins attaches to the bit, without tension at first, but in due time fastened with the snaffle reins.

All these straps being adjusted, I take the end of

the longe in my left hand and back away to very nearly the full length, while an assistant holds the

horse's head. I stand at the center of the circle in which the horse is to travel, and show the long training whip, which I carry in my right hand. The assistant leads the horse a few steps around the circle to the left, then stops and caresses the animal on neck and head.

When in this way the horse has traveled an entire circumference, the assistant lets go the bridle, and takes the longe with his left hand about three feet from the head. While the assistant continues to caress the horse with his right hand, the trainer, still holding the longe in his left hand, encourages the horse to continue around the circle, by chirping the tongue and showing the whip near the horse's hind legs, but without actually striking. After a few trials, the horse comprehends what is wanted, and goes forward at command. Thereupon, the assistant works progressively farther and farther along the longe away from the horse, until he lets go entirely.

As the horse learns to travel around the circle under control of the trainer, it must learn also to stop on the line, without turning its body inward or outward. For this, the trainer swings his left hand up and down, so as to give a succession of mild jerks on the longe; at the same time, the assistant walks slowly along the longe to the horse's head, while the trainer, in a clear and commanding voice, calls, Hoho, Hoho. Whoa! As the horse stops, the assistant caresses it. At first the animal will turn its haunches outward from the circle. After a few lessons, it will stop straight on the line.

The trainer should always stand still at the center of the circle, never following the horse, but compelling the horse to go round him, to walk, trot, and stop as indicated, but not to come to the trainer unless summoned by a pull on the longe.

An experienced trainer will very soon teach the horse to obey the whip. Shown near the flanks, it means to go to the right or left; at the hind hand, to go forward at the different gaits; in front of the face, to stop. Showing the whip straight, the lash upward, accompanied by a gentle tug on the longe, will bring the horse to the center. If the horse is then rewarded and caressed, the sight of the whip held vertically will alone be sufficient without the pull on the longe.

At the beginning of this work, the reins should not be at all tight. It is, however, impossible to lay down any rules as to their precise tension. An experienced trainer judges, by the animal's temper, conformation, energy, length of neck, and sensibility of mouth, what the effect of the bits will be. In fact, an experienced trainer could fill ten volumes with accounts of the diversities among horses and the various difficulties that he has encountered and overcome. Something less than this, however, confined to principles and method, will better please the publisher and hearten the reader.

Three months is sufficient, by this method, for breaking a horse to the lateral equitation. But if the horse is mounted from the beginning, it will take at least a year, often longer.

When the young animal has made sufficient progress with longe and breaking-strap, the surcingle is removed, and the horse, standing still, is mounted and dismounted by the assistant, the trainer meanwhile holding the longe near the head. After this, the assistant being mounted, the trainer sends the horse around the circle as before, walking, stopping, trotting, cantering, while the assistant, under the direction of the trainer, applies the proper effects of legs and bridle. All this should be done both to the right and to the left, as explained in the discussion of figures of manege.

As soon as the horse has become calm and obedient while the hands of the assistant feel a gentle contact with the mouth through the rein, the cavesson likewise is removed; and the trainer, now mounting for himself, begins progressive work

upon the several gaits, first on a straight line, afterwards at the figures of manege, but always, without exception, by means of the lateral effects.

It is best, when possible, to keep the horse for a year at the breaking in and the lateral effects, before going on to the reasoned equitation. By that time horse and trainer better know one another, the horse is stronger, steadier, and better able to profit by the suppling of the flexions. Moreover, the young or inexperienced trainer is very likely to push his horse's education too hard, and to neglect some items which do not seem important to him. The result is that there comes a time when the trainer has to go back and pick up these neglected elements.

Often, too, it happens that a horse, well trained by a master, is ridden by some one without equestrian tact, and has to go back to the master to be retrained. Sometimes, also, a man buys a horse which has already been ridden, but in accordance with some other method than his own; and since the memory of the horse is very persistent, the training may have to be started over again from the foundation.

In all these cases the trainer needs to be experienced, patient, persevering, energetic, and positive, besides having a genuine affection for his pupil. No two horses are alike in conformation or morale, nor in the results of their first contact with man. The trainer needs, therefore, to diagnose his animal, to consider his strong and weak points, so as to pick the right place for the training to begin. If, for example, a horse is anxious and timid, before I do anything else, I give it confidence, by means of work on foot with the whip. If it is young and not strong. I develop its muscles by means of the cavesson with the Bussigny breaking-straps.

One ought, in a word, to study his horse, find out its special needs, and commence the education by removing the causes of its imperfections. Methodists, as a whole, are too sure of their general principles. They want to have every horse put through the hard-and-fast progression of their particular method. But my experience is that each individual horse has its own physical and moral disposition, and that each needs its own special treatment and training.

This much, at any rate, is certain: no matter how the horse's education commences or proceeds, the earlier portions of it will need more care, more ability, and more experience on the part of the trainer than the later ones. I am, then, fully agreed with Baucher in his criticism of owners who give young horses to their stable grooms to train. And yet, in Baucher's time, equitation was in high esteem. Whereas now horsemanship is almost a lost art, and riding is thought of merely as a wholesome exercise.

CHAPTER X

REWARDS AND PUNISHMENTS

Caresses and other rewards are the first means by which the trainer makes the horse understand that it has nothing to fear when under control. A horse is by nature timid and anxious; the first step in its training is to give it confidence and to make it understand that it will meet no ill usage. When that is accomplished, the horse is tamed. As yet, however, it knows nothing. Its education advances by means of rewards when it does well, and by punishments when it fails to do something that it has already been taught.

Caressing may be done with the hand alone, or with the voice, or by the two in conjunction. Early in the training, it is better to employ both together, so that each may help to make the other understood. After the horse gets the idea, it is better to use only one at a time.

When the man is on foot, he commonly caresses the horse by passing his hand over the forehead below the forelock, always in the direction of the hair. But the horse should become accustomed to caressing on other parts of the body—neck, shoulders, loins, abdomen, haunches, and legs. The fingers should be extended and the full hand used, not merely the finger-tips. The horse is thankful for a generous caress with heart in it.

On the other hand, the horse should not be slapped too strongly. A nervous animal, especially, is likely to interpret this as a reproof.

Caressing by the voice is entirely a matter of softness of tone. The animal has no idea whatever of the meaning of the words.

With the horse in motion, whether walking, trotting, or galloping, whenever the rider feels it becoming anxious at the sight of some object or at some noise, or hesitating before an obstacle to be cleared, he commonly employs the voice to quiet or encourage the animal, since the hands are busy with the reins. But standing still, or whenever, in motion, the rider can manage the reins with one hand, the free hand should caress the particular part of the body which has obeyed the rider's signals or been the chief factor in the movement. If the neck has played the leading part, caress the neck. If the croup, caress the haunches or loins. By this means the horse is trained to associate the aids and signals of the rider with the part of the body which is to carry out the command.

In general, a reward given during the act of obedience is more effective than one administered later. It is, therefore, often wise to repeat a movement, already executed correctly, for the sake of giving the caress during the actual performance. But after a difficult movement, well performed, it is often best to dismount, take off the bridle, give a carrot, an apple, or a piece of sugar, and dismiss the pupil to the stable.

Punishments, in the horse's education, are no less important than rewards. These ought always to be administered fairly and justly, with decision, but without impatience, calmly and with self-restraint, and with a sentiment of regretful loyalty on the part of the man.

The means of correction are four: the spurs (to be discussed later), the whip, the voice, and the hand. The whip is especially effective. It is used with sharp but not severe stroke, upon any part of the body, but never on the head. After the training has made some progress, the effect of the whip is augmented if, along with the stroke, the trainer speaks in a sharp, guttural tone. A man working his horse on foot can make a strong impression by looking the animal straight in the eyes, with a severe countenance, while he speaks harshly with the voice. After this, the whip may be suppressed, and the rebuke given by a severe slap of the hand, accompanied by the threatening tone. The same method may then be used mounted.

When the horse has learned to expect punishment when it misbehaves and rewards when it does well, and to trust its rider always, it is well on the road of a progressive and thorough education.

CHAPTER XI

THE FIRST WORK ON FOOT

The breaking in has for its object merely to accustom the young horse to the feeling of harness, girths, and saddle, and to the beginnings of control by the trainer. The early work on foot is but a continuation of the breaking in. Its object is to lead the green animal to understand the various contacts and effects, of which, of course, he is, at the beginning, completely ignorant. By this preliminary work on foot, we educate the horse to submit to the contact of the bits, which at first cause an anxiety which must be completely overcome.

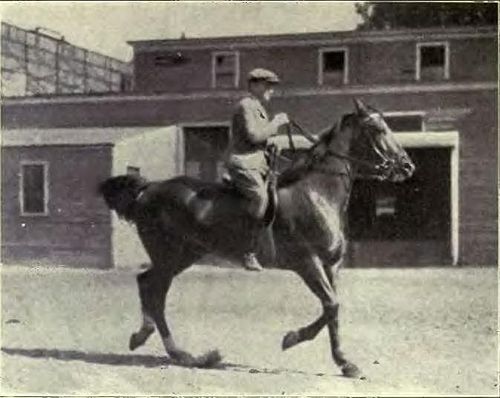

The horse, saddled and bridled, is led to the spot selected for the first lesson. The stirrups are raised on the saddle, and the snaffle reins are passed forward over the head, and held in the left hand of the trainer, who stands in front facing the animal, the whip in his right hand. The man speaks soothingly, exhibits the whip, and with it caresses the horse's forehead, nostrils, ears, and both sides of the neck. (Figure 1.)

At first, the horse will be uneasy. But shortly he becomes calm, finding that no pain follows the touch of the whip, and encouraged by the man's voice and his complete immobility. Thereupon, the

trainer raises the whip, and stepping backward, he pulls lightly on the two snaffle reins. When, by this means, the trainer obtains two or three forward steps, he immediately caresses the animal by voice and hand. After a few days of this training, the horse will, of its own accord, advance toward its master as soon as the whip is lifted to the height of its head. As soon as this happens, the pupil should be caressed with the whip on shoulder, chest, croup, and all four legs.

When the horse no longer has the slightest fear of man or whip, the time has come to teach the animal to move forward in response to other effects. The trainer, facing forward, stands at the horse's left shoulder. In his right hand he holds the two snaffle reins, three inches from the horse's chin; and in his left hand he carries the whip, the lash behind and near the horse's flank. In this position he impels the horse to walk forward by light touches of the whip on the flanks near the girths. (Figure 2.)

At this point the horse will sometimes hesitate, or even try to back. But the trainer, remaining always calm, encourages the animal with his voice, which the horse already knows. By drawing forward steadily with his right hand, he should always succeed in obtaining a few forward steps. These, if well recompensed by caresses, will very soon be followed by more at the same signal.

If the horse manifests irritability or violence, the trainer should pass the snaffle reins forward over its head, and while holding them with the right hand near the chin as before, he should also take them near their ends with his left hand, which holds the whip. If, then, any violent movement of the horse forces the trainer to let go the reins with his right hand, he still has the other grip to fall back on.

As soon as the horse advances readily and takes the contact of the snaffle bit against the lower jaw, the training is to be repeated from the other side. When the contact is accepted freely with the snaffle, the same course is repeated with the bit. In this case the little finger of the left hand separates the two reins of the bit, and the ends of these reins leave the hand between the forefinger and the thumb. The snaffle reins, on the contrary, enter the hand between the forefinger and the thumb, and pass out at the little finger. All five digits close upon the four reins.

From this position the trainer urges the horse forward with the whip, as before, against the snaffle. Then, when the horse is moving, he substitutes the contact of the snaffle for that of the bit, by bending the wrist to carry the thumb forward and the little finger backward. This movement of the hand must be done very gently and carefully. When the contact can be made with the trainer on the left side, the same operation must be repeated from the right, with everything reversed.

This procedure is advocated by Fillis, who holds that the whip, acting upon the flank, will help to make the horse understand the action of the rider's legs, at the later stage when the animal is mounted. In this, Fillis is essentially right.

Baucher's practice is somewhat different. He faces the horse, taking, at first, the two snaffle reins in his left hand, and later, bit reins and snaffle reins alternately. With the whip, held in his right hand, he makes light touches on the horse's chest. The horse, thereupon, backs. But as the touches continue, the horse, finding backing of no avail, decides to go forward. It is thereupon rewarded with caresses, until, very shortly, merely showing the whip near the chest will obtain forward movement and contact with the bits. (Figure 3.)

CHAPTER XII

THE FLEXIONS

THE horse, when not under the control of the man, balances himself instinctively by different positions of head and neck. But the horse under control has these various positions given to him by his rider, by way of the bits. But the feeling of the bits in his mouth is disagreeable to the horse. The result is a tendency to contract and to keep tense the muscles which close the lower jaw, on which the bits rest. This disagreeable sensation tends, moreover, to affect the entire body, and to produce a general condition of contraction, opposition, and refusal.

The object of the flexions is, by means of certain graduated exercises, to teach the horse that no real pain will follow these uncomfortable sensations, and to suppress their general accompaniments, while accustoming the animal to obey their special effects.

The hands holding the reins can, by different positions and manipulations, produce on the animal mechanism a great variety of effects, of which the three principal are, directing, raising, and maintaining. The work of the flexions will introduce the horse to these different effects, which later, after the rider is mounted, will be further complicated by the effects of the legs.

A brief consideration of the bones, joints, and muscles involved in the flexions will help in avoiding certain mistakes.

The bars, on which rest the bits, are the distal part of the lower jaw, between the molar teeth and the incisors. In conformation they are of three types. In one sort the bone is small, and covered by a thin mucous membrane. Such bars are said to be "sharp," and are especially sensitive to the pressure of the bits. Another sort has a large bone, somewhat flattened where it meets the bits, and covered with thick mucous membrane. This sort is commonly little sensitive, and is described as "fleshy." The best type of bar is intermediate between the two.

The temporo-maxillary articulation which connects the lower jaw with the skull lies between the ears and the eyes, just behind the frontal bone. It allows the jaw, moved by the digastricus, masseter, and temporalis muscles, to open and shut, to move laterally for mastication, and to glide back and forth. This joint plays an important part in equitation.

Another important set of bones are the vertebrae of the neck. The first cervical vertebra, the atlas, articulates with the occipital bone of the skull. Next to it comes the axis. These two vertebrae form the atlo-axoid articulation which permits the head to rotate upon the axis, this remaining fixed. The occipito-atloid articulation, on the other

hand, permits four motions, extension, flexion, lateral inclination, and circumduction. Its movements are given by the muscles of the neck, obliquus capitis, sterno-maxillaris, rectus capitis, scalenus, longus coll, splenius, and angularis scapulae. All these muscles are either attached or related to the three other muscles which work the lower jaw. They are, therefore, most intimately concerned in the position which is given to the head and neck, through the sensation of the bits on the bars. It is the position of the head and neck which is the object of the flexions.

Two other especially powerful muscles of the neck are concerned primarily with locomotion. The rhomboideus is connected at the atlas region with the other muscles of the head and neck; but when this atlas region is fixed, it draws the shoulder forward and upward. It is, therefore, related to the scapulo-angularis and latissimus dorsi of the chest. The other large muscle, the mastoido-humeralis, has also one of its ends at the atlas region, and the other at the shoulder and chest. When the atlas region is fixed, at the same time that the rhomboideus lifts the fore leg, the mastoido-humeralis carries it forward. But if the chest region is the fixed point, this muscle draws the head and neck to one side. It is by means of the flexions that we obtain for these two muscles the fixed point in the atlas region. When the horse accepts contact of the bits on the bars, the rider controls directly the muscles of the head, and indirectly those of the neck. Thus by the continual communication of this indirect effect, which in its turn, emanates from the first direct effect of the bits on the bars, the rider controls also the action of the front limbs.

Here, then, is the theory of so much of the animal mechanism as is exercised by the flexions. I urge the trainer, at this point, to regard as essential the character of the flexion obtained by his work, rather than its amount. The important matter is not that the horse shall bend its neck more or less readily, but that it shall respond with head and neck to the tension of the reins; that it does not cease this tension of its own will, but while keeping the contact of the bits, shall obey this tension consistently.

It is desirable for the horse's education, not to commence this work of the flexions unless there is to be time to complete it. Further consideration of the bones, joints, and muscles involved in locomotion will be found under the caption, "Legs and Their Effects" the same illustrations serving for fore hand, trunk, and hind hand.

The masters of equitation before Baucher had already employed a system of flexions for suppling the neck; but they failed to recognize the importance of a further suppling of the mouth. Baucher, in his reasoned equitation, saw the need of suppling the mouth also, and developed a series of flexions for both the mouth and the neck.

Fillis objects to the execution of Baucher's flexions on the ground that he bends the neck at the region of the third vertebra and not at the atlas region. The series of flexions by Baucher is very complicated, those of Fillis are very strenuous; the two are difficult of execution for a young trainer.

To remedy these difficulties, I have created a series of flexions similar as to object to those of the two grand masters, but more easy of execution and sufficiently comprehensive for the trainer and the horse. The first condition, sine qua non, is to teach the horse to sustain the head and neck high up, by its own effort and without the help of the trainer. To obtain this result, the trainer places himself facing the head of the horse, holding the left snaffle rein in his right hand and the right rein in his left. By raising his two hands straight upwards, not backward or forward, the horse will raise head and neck. (Figure 4.) When the head and neck are up, the trainer opens the fingers of the two hands maintained at the same height; but if the horse drops its head or neck, the trainer shuts his fingers quickly. The flexion is complete only when the horse holds the head up without help. (Figure 5.) It then becomes a question of obtaining the flexion of the mouth without letting the head change the high position. For this flexion, the trainer, facing the head and neck from the left, and holding the right rein of the bit in his right hand and the left rein in his left, causes a pressure on the right bar by

the right hand, which, acting progressively, forces the horse to open its mouth. The head is slightly inclined to the right, but sustained high, the slightest derangement of the head or neck being corrected by the left rein held in the left hand, which is carried upward, downward, forward, to the right or to the left, according to the effect necessary to correct the false position taken by the head or neck in resisting or preventing the proper position and flexion. (Figure 6.)

When the depression of the lower jaw is obtained, the head being lightly inclined to the right, the trainer, by carrying his left hand progressively backward, places the head straight, always continuing the flexion of the mouth. When the head and neck are inclined to the right or to the left, the flexion is called the right or left lateral flexion. The flexion is called direct when the head and neck are straight. The two lateral flexions are only the means for obtaining the direct flexion, which is only complete when the horse depresses its lower jaw. (Figure 7.) The effect of the bits upon the mouth and neck produces a cause and effect. The mouth refuses because the neck resists, the neck refuses because the mouth resists. This difficulty is found in the different conformations, and to obviate it, the alternate flexions of mouth and neck are the proper work.

For the flexions of the neck, the trainer places himself on the horse's left side near the head, takes the right rein of the bit with his right hand and the left rein of the snaffle with his left hand. The flexion of the mouth is obtained by the right rein and the flexion of the neck by the left hand carried to the right over the nostrils of the horse. (Figure 8.) The lateral flexion of the neck is complete when the head is turned facing to the right. After the lateral flexion of the neck, the head is to return to the direct flexion, by the rein or reins of the snaffle. If the horse has a thick, short, and fleshy neck, it is proper to enforce more bending from the neck. For that purpose the trainer places himself on the right side of the horse for the lateral flexion to the left, holds the right rein of the snaffle in the right hand and the left rein in the left hand. The left rein, bearing upon the neck, is kept at the same tension by the left hand, assuming that the right hand allows the head to flex to the left and follows the head in its flexion backward, so that, by raising the right hand, the head is maintained perpendicular and flexed at the atlas. (Figure 9.)

This position of the head flexed perpendicularly has to be obtained by moderate progress, passing from the position in Figure 9 to that shown in Figure 10, and finally to that obtained by the bit alone in Figure 11.

After arriving at this stage, the trainer continues the direct flexion of mouth and neck. The two reins of the bit are held in the left hand, and the two reins of the snaffle in the right, the forefingers

between each pair of reins. The left hand operates a progressive but continual tension upon the bit, while the right hand corrects with the snaffle the false position possible at the beginning and thus secures the flexion at the atlas only. (Figure 12.) The flexion is completed when the mouth is open.

Finally, to obtain proof of the quality of my work of flexions, the horse straight, the head up and light, and yet in contact with my hands, I place myself facing the horse, the left reins of snaffle and bit in my right hand, the right reins in my left hand, and by a progressive and moderate action of my two hands, I obtain the direct flexion of mouth and neck, the horse keeping the same position of body. (Figure 13.) At the completion of the flexion, the horse is upon the hand, with the lower jaw completely depressed. (Figure 14.) The flexions have to be executed equally to the right and to the left by the same principles, but by the opposite means.

In explaining above the principles of the flexions, I have changed sides several times in order to make it possible for the photographer to reproduce on the plate the position of hands, reins, head, and neck, so they will be more apparent to the reader.

The next step is to secure lightness. The trainer stands facing his horse, with the right snaffle rein in his left hand, and the left rein in his right. By repeated vibrations he raises progressively the head and neck, until, after a few lessons, the horse re- mains straight and still, head and neck elevated, without the help of snaffle or bit.

As soon as this position of lightness is obtained, comes the flexions of the jaw. The trainer, holding as before the two snaffle reins, makes very light oppositions, but without allowing the head or neck to drop. Now begins the "fingering." By this I mean the repeated, rhythmic opening and shutting of the mouth: mouth shut, bit contact, fingers closed on the reins; then mouth open and fingers unclosed, the hand always at the same height.

When the lower jaw is depressed squarely at the effect of the snaffle, the trainer repeats the same exercise, holding in each hand a rein of the snaffle and one of the bit. The snaffle maintains the position of head and neck, while the bit controls the depression of the jaw. But the effect of the two, especially of the snaffle, is peculiarly upon the atloaxoid articulation.

But while this flexion is the most important of all, it is nevertheless so entirely at the atlo-axoid joint that the rhomboideus and mastoido-humeralis muscles are so completely contracted that they do not, in this condition, gain the development which is desirable and which is so noticeable in the neck of "Why-Not."

For all this work, especially, I recommend patience, perseverance, and slow advance. What counts for the future is the quality of the performance. The quantity is a small and temporary matter.

The series given above is sufficient to teach the rider the manipulation of the reins, and to train the horse to yield by mouth and neck to the effects of the bits. Many other flexions have been worked out by methodists to meet special difficulties of conformation and temper. But such a variety of cases is outside the limits of this book. Those which have been given, done first on foot and then mounted, are quite sufficient for suppling neck and mouth.

CHAPTER XIII

BACKING AND THE PIROUETTES

THE pirouettes are revolutions of one end of the horse's body about the other. In the direct pirouette, the hind feet remain in place, while the fore feet circle around them, either to the right or to the left. In the reversed pirouette, called rotation by the new school, the shoulders are the fixed point and the haunches turn around them.

The reversed pirouette is the first movement of the reasoned equitation. It is also the most important, since on its correct and symmetrical execution the entire education depends. It has, moreover, three stages: the reversed pirouette in lateral, which belongs to the lateral equitation; the direct rotation, which belongs to the reasoned equitation; and that in diagonal, which belongs to the scientific equitation. The three terms, lateral, direct, and diagonal, refer to the lateral, direct, and diagonal effects by which the movement is obtained.

The first step in the horse's education is, of course, the position of "in hand"; which has already been considered in the account of the flexions, and will be discussed still further in Chapter XXII. Up to this point the horse has been trained to take the position given by the rider's hand while standing still. It does not yet understand how to move its weight on its feet, and at the same time, to remain in hand. The grand masters have, therefore, spoken of the direct and reversed pirouettes as the mobilization, respectively, of the front and hind hands.

THE REVERSED PIROUETTE

IF the horse has been given the work with the trainer on foot, already described, the reversed pirouette should also be taught on foot. If the training is done in a manege, the animal should be in the center of the ring. I shall discuss first the reversed pirouette in lateral from right to left.

The trainer stands on the horse's right, between head and shoulder. The right hand holds three reins, two from the bit, with the little finger between them, and the right snaffle rein, which passes from the thumb to the little finger. But the snaffle rein is held shorter than the rest. The whip is held in the left hand, with the lash near the horse's right flank.

By means of the reins from the bit, the trainer holds the horse in hand, and at the same time, with the snaffle rein, he obtains a partial lateral flexion to the right. He calms the animal by his voice, and still keeping the "in hand," he keeps touching the right flank lightly with the whip.

Commonly, at this, the horse will either back or raise the right hind leg. If the horse backs, the trainer will correct the fault by carrying forward the reins. But if the horse merely lifts the right hind leg, showing neither fear nor impatience, then the trainer is satisfied and rewards the action with caresses. After a brief relaxation, the action is repeated from the beginning.

Sooner or later, however, the animal, instead of merely lifting the right foot, will, in addition, carry it to the left, under the body, and set it down more or less in front of the left foot. In that position, before the right hind foot can be lifted again, the left hind foot must also gain ground leftward. (Figure 15.)

This is the first step of the reversed pirouette, the beginning of the mobilization of the hind hand. In a short while, the horse comes to understand that when its right flank is touched with the whip, it is to lift the right foot and step toward the left. After the first step, the second, third, and fourth are readily obtained in the same way. Four such steps, done in proper cadence, are enough. More will disturb the support of the front legs, and will distress the horse, since they are against its natural conformation.

Meanwhile, of course, the horse will have lost the "in hand" position. The only remedy is patience, perseverance, and quality of work. You, Master, are the instructor. You are teaching to your pupil the alphabet of locomotion. On this foundation, your pupil may, in time, become a most

uncommon animal. Do not forget that your whip has still to be replaced by legs and spurs. So do not hurry. Take ample time, remembering that the more time you take at this stage, while still maintaining the quality of your work, the faster progress you will make in the end.

When the lateral rotation is thoroughly mastered to the left, everything is reversed and the movement made toward the right.

In the reversed pirouette, as also in the passage, the trainer must not, under any condition, allow the horse to begin the movement by stepping off with the hind leg on the side toward which the motion is to be made. If, for example, the step is to be toward the left, the right hind foot must first cross over in front of the left. After that, the left foot steps still farther to the left. But the left foot must never move first. In other words, the legs always cross, never straddle.

I cannot insist too strongly on this point. Baucher followed and taught the opposite method, and it gave rise to much confusion in his principles. Moreover, it occasioned terrible fights against horses trained by him, which became confused by the effects of the legs.

When the reversed pirouette is correctly executed in lateral, it can next be readily obtained with the direct flexion of "in hand." For this, the pull on one snaffle rein is suppressed, and the horse's head and neck are held straight, while the four steps of the movement are asked by means of the whip. (Figure 16.)

The reversed pirouette in diagonal belongs to the scientific equitation, and will be taken up with that subject.

THE DIRECT PIROUETTE

THE direct pirouette, usually termed simply the pirouette, is the first movement for mobilizing the front hand. Assuming for convenience of description that the movement is toward the left, the action is as follows:

The left hind leg becomes the chief support of the hind hand, while the right hind foot, as in the reversed pirouette, passes in front of it to the left. Then, in its turn, the left rear foot, without in the least altering its place on the ground, turns on the same spot to face in the new direction. These two alternate, the right foot really stepping round the left.

Meanwhile, the right fore foot passes in front of the left, thus crossing the fore legs. As soon as this has taken the weight, the left fore foot moves off to the left, and restores the first relation. In this manner the fore hand walks round the left hind foot. For movement in the other direction, everything is, of course, reversed.

To obtain this pirouette to the left, the trainer stands on the horse's right side, as for the reversed pirouette, facing to the rear. In his right hand he holds the two snaffle reins close behind the chin. The whip is in his left hand, lash near the horse's flank.

The horse being held straight and "in hand," the trainer, with his right hand, pushes the animal's head straight to the left, while, at the same time, by means of the whip, he checks the natural movement of the haunches toward the right. Thus, by pushing the fore hand round in one direction, and at the same time preventing the hind hand from circling after it, the trainer soon obtains the first step of the pirouette. Then follows the usual pause and caressing; and shortly, the animal learns to complete the action. After this, the direction is reversed.

BACKING

THE pirouette has now taught the horse to mobilize the fore hand. The reversed pirouette or revolution has taken care of the hind hand. There still remains the mobilization of the entire length of the spine, from the atlas region to the last of the sacral vertebrae. While this remains straight and rigid, correct locomotion is not possible.

Flexion of the spine hinges on the " coupling" between the last dorsal vertebra and the first sacral, which has to bend with each step forward, sidewise, or backward. Unfortunately, this articulation tends to become ankylosed with advancing age, and even in a young animal the unnatural load of the rider tends to stiffen the joint. Both causes interfere with free movement, and occasion kicking, rearing, and buck- jumping.

It is, therefore, essential, during the work on foot, to complete the mobilization of the entire body by exercise in backing to supple the coupling.

Some authors advise, for this purpose, having the trainer stand in front of the horse, facing it, and with one rein in each hand, either of bit or snaffle, pushing the animal backward by "sawing" back and forth on the bridle. Fillis advocates having the man, in addition, step on the horse's feet, first on one, then on the other, as the sawing goes on.

But how, I ask, is the horse to understand that it is to flex its spinal column, just because somebody saws its mouth or walks on its feet? I myself proceed in quite a different manner. I put my horse straight, right side near a wall, "at left hand," as it is called. I stand at the shoulder, whip in my right hand, snaffle reins in my left. With the whip, I touch the back close behind the saddle, repeating several times, very gently, never at all violently or severely. Meanwhile, I pull lightly on the snaffle reins. Commonly, within two minutes, the horse lifts one hind foot. If at this moment I pull on the reins, I hinder with my left hand the movement forward of this leg, which will at once be carried backward. The diagonal front leg will at once follow, and I have obtained the first step. Caress- ings on the croup with the right hand, accompanied by the voice, soon make the horse comprehend what is desired. A single one-hour lesson is sufficient to teach the creature to go backwards, the coupling supple, at the touch of the whip behind the saddle and the gentle tension on the reins. The movement should then be repeated from the right side, reins in the right hand, whip in the left.

This movement backward, alternated with the other movements, forward, pirouette, and reversed pirouette, will very soon bring about a state of complete obedience on the part of the horse. The man, on his side, begins to see the effects of the various means which he is employing and to understand the operation of the animal mechanism.

During the work on foot, if the horse is uneasy from need of exercise, put him at the cavesson and longe, preferably without bridle.

A last word : Patience and gentleness; do not forget that you teach, you educate.

CHAPTER XIV

THE HANDLING OF THE REINS

BEFORE proceeding to the further training of the horse with the rider mounted, it is necessary to consider more fully than under the instinctive equitation, the position of the rider's hands and the manipulation of the reins.

No fixed position of the hands is correct for all occasions. What it should be in each special case depends on the degree of education of the horse, on its action, sensitiveness, temper, conduct. It varies with the surroundings, the gait at which the animal is traveling, the character of the road, the state of submission or disobedience. It is modified also by the ability of the rider. It alters from moment to moment with the change of circumstances. All that one can do, therefore, is to give the general principles involved, and the standard position from which variants are taken as conditions change.

Let us, then, suppose a horse, well conformed, properly trained, and quiet, ridden at the promenade trot, by a good ordinary rider with a good seat, in street, road, bridle path, or manege, but without all the paraphernalia and impedimenta generally met with in such conditions. In such a case, the hand will be carried six inches above the pommel, the little finger down and slightly nearer the body than the thumb. The thumb is up and closed upon the four reins, which fall forward of the hand and to the left, when, as is usual, the reins are in the left hand. The fingers touch the palm at the nails, pressing with just enough force to prevent slipping. The hand is exactly opposite the middle of the body, and exactly in line with the horse's neck. The elbow touches the side without stiffness or pressure.

When, for any reason, the hand is moved from this position, one inch upward, downward, or sidewise, is in general sufficient for the full effect of the change. If for any reason, some other position has to be taken for the sake of conduct or control, what this new position shall be is decided by practice and experience according to the particular circumstance. If, for example, the horse rears, the hand should be dropped as low as possible, the rider leaning forward. If, on the other hand, the horse kicks, then the hand is lifted as high as possible, while the rider leans back and lifts the animal's head.

For the rider on a side-saddle, the position is the same, except that the hand is two or three inches above the right thigh.

During the process of training a horse, the position of the hand varies so greatly that no rules can be given. The master will, therefore, vary his position to meet special problems of mouth or neck or of the two together, and all the various contractions and defenses of the horse, as his experience suggests.

In ordinary civilian equitation, in the case of men and occasionally even in the case of amazons, there is really no particular reason why the reins should be held with the left hand rather than with the right. But the army man, the hunter, the polo player, and the woman who uses her whip to produce the effects of a right leg, are obliged, naturally, to keep the right hand free for saber, pistol, mallet, or whip, and to use the left hand only for the reins.

For beginners, for all riders mounted on animals not properly bitted, and oftentimes with hunters and park hacks, it is an advantage to hold the reins in both hands. Both in the hunting field and on the promenade, it is sometimes difficult to keep the horse straight at an obstacle or straight on the road. Evidently, in these cases, the rider has better control, and easier, if he does not have the complication of four reins in one hand.

When both hands hold the reins, each taking those on its own side, the snaffle rein passes under the little finger, and that from the bit lies between the little finger and the third finger. Both then pass upward and forward, above the forefinger, held against it by the thumb. When both reins of the bit are held in the same hand, together with one snaffle rein, the other snaffle rein being held alone in the other hand, the tvwo hands should be kept at exactly the same height, and never more than three inches apart. To make an effect to either side, the hand is carried three inches horizontally, without any tilting of the hand upward or downward.

The reins of the bridle, whether held in one hand or both, are pressed by the fingers only just hard enough to prevent slipping. If the pressure is too strong, the tension will be communicated to the arms, and from them to the whole upper portion of the body. At first sight, nothing seems easier. But in practice, the reins will slip, and unequally. The result is that, when the rider has occasion to draw on the reins, the one which at the moment happens to be shortest, has the most effect.

It becomes necessary, therefore, from time to time, to readjust the reins in the hand.

Suppose that all four reins are held in the left hand. To adjust, let us say, the curb reins, which are those without the buckle, the rider, with his right hand behind the left, takes the free ends with his thumb and first finger, and carries the right hand upward, while at the same instant he relaxes the grip of the left hand on these two. Meanwhile the left hand is kept precisely in line with the horse's neck. As soon as the rider feels with the right hand the equal contact against the mouth, he closes once more the fingers of the left hand and lets go with the right. For the snafHe reins, those with the buckle, the process is exactly the same.

With the reins held in both hands, to adjust the left reins the rider brings the right hand up to the left, takes with the thumb and first finger as before the reins which have slipped too long, relaxes the grip of the left hand, and draws the reins upward to the proper length. If the reins are too short, they are taken in the same way, but in front of the left hand, and drawn forward. For the right rein, the process is exactly reversed.

It is difficult, usually, to teach a beginner properly to close his fingers on the reins; particularly women, who handle the leather as if it were fine lace, and never really grip it firmly nor have the correct length. Yet grip and length are even more important for women than for men, since the latter have the better control by way of legs and saddle. With both men and women, the fault commonly begins during the early lessons in the ring. If not corrected then, it persists as a bad and dangerous habit, so that one often sees even good riders who have always to be adjusting their reins.

Sometimes, for control or for safety, it becomes necessary to shorten promptly some or all of the reins. Beginners carelessly let them slip through the fingers. Many older riders abandon control of their horses or think it proof of a good hand to have the reins too long. The result is that in sudden emergency — as, for example, when the animal by a sudden jump disturbs the seat — the rider can do nothing until he has taken time to shorten his reins. Then it may be too late. While, therefore, even the beginner ought to learn to keep his reins always at the correct length, he should be practiced also in shortening them instantly.

The method is much the same as for adjustment. If the rider is holding all four reins in the left hand, he simply seizes them all with all the fingers of the right hand, or certain ones with thumb and forefinger, and draws them upward to the needed length.

I often tell my pupils that the beginner has always two enemies of his safety — his eyes and his fingers. The eyes never look far enough ahead to see where the horse is going; therefore they tilt the head forward and displace the body. The fingers let slip the reins; therefore are these not ready when needed to control the horse.

I have already noted that the determining factor in handling the reins is the need of holding the horse straight, the backbone acting, so to say, as a sort of keel; and that, on the whole, it is easier to accomplish this end when both hands are employed. Nevertheless, there are conditions which make it at least convenient for the time being to change from two hands to one or from one to two. If, for example, the rider regularly uses the left hand for all four reins, in order to have the right hand free for whip or mallet, he may often need to use both hands to control a case of excitement or refusal.

To separate the reins, changing from the left hand to both hands, the little finger of the right goes over the right snaffle rein, with one finger, or better two fingers, between this and the right rein of the bit. The bit rein is slightly the looser of the two.

It is impossible to give the precise detail of this movement. It has to vary somewhat with the way the reins are carried in the left hand. For much the same reason, it is not possible to dictate the relative length of the two reins, since this is affected by skill of the rider, the speed of the horse, and its education, temper, and surroundings. With certain horses, in certain conditions, at various speeds and gaits, certain ways of holding the reins are better than others. I have experimented widely, and I am convinced that virtually all the methods of the various masters are good in an "intelligent" hand. It is not any fixed position of the reins which gives control over the forehead of the mount, but the effects of hand and fingers on the bits. An able esquire will produce the same total effect with the snaffle or with the bit, with left hand or right hand or both. It is all a matter of equestrian tact.

One cannot, then, dictate the precise method of separating the reins until he knows how they are held all together. But whatever the method, the pupil should be frequently practiced in changing from one hand to both and back again. These manipulations are to be executed, first standing, and later at all three gaits, without changing the regularity of gaits and speed. Then is the beginner prepared for emergencies.

There are three principal methods of crossing the four reins in one hand.

According to the first of these, the rider, as soon as mounted, takes the extremities of the snaffle reins in his right hand and places them upon the middle of the horse's neck. He next takes in his right hand the two reins of the bit, also by their ends, and, lifting his hand, gives these a moderate tension. He now places his left hand over these two reins, his little finger between them, and grips them with all four fingers. The free ends pass out between the forefinger and the thumb, which closes on them, and fall to the left side of the hand. Finally, the rider picks up the snaffle reins with his right hand and raises them in front of the left. His left hand thereupon looses its grip with the three upper fingers, but, still holding with the fourth, passes the middle finger between the two snaffle reins, and shuts the thumb against the free ends of both pairs.

For the second method, the rider, as before, lays the snaffle reins on the horse's neck, lifts the bit reins with his right hand, and grasps them with his left. In this case, however, both the third and the fourth finger separate the two bit reins. He next takes the two snaffle reins in his right hand, and passes them between the first finger and the thumb of his left hand, bringing them out below the little finger. The thumb, as before, shuts upon all four reins.

According to the third method, the left rein of either the bit or the snaffle is placed below the little finger, and the left rein of either the snaffle or the bit passes between the fourth finger and the third. The right rein of the snaffle or of the bit is between the third finger and the second, and the right rein of bit or snaffle is between the second finger and the first. Thus a finger separates each two adjacent reins.

One last manipulation of the reins remains to be considered—the ancient practice of jerking the bit.

The old school of equitation recognized this action as a means of controlling a disobedient, restive, or vicious animal. At that epoch only stallions were ridden; and the character of the riders had to match their mounts. Pluvinel, de la Broue, and Grisons recommend that, in case a horse refuses to turn to the right or left, to change from gallop to trot, or from trot to walk, or to stop, the rider should "give him several sharp jerks against the mouth; and in the mean time call him with a strong voice, 'Pig!' 'Cow!' 'Scoundrel!' 'Coward!' 'Felon!'" a complete vocabulary of epithets not understood by three quarters of humankind.

Of course these excellent masters did really produce the effects they desired; but it was by the sound of the voice, not by the epithets. Moreover, the jerk on the bit cannot have any other result than to destroy the animal's understanding of the effects of the bit by making him fear the pain.

Jerking the bit is, then, a proof of lack of both kindness and competence on the rider's part. For after several repetitions, the horse, remembering the pain, expects still another jerk whenever the rider does anything with the reins; and in order to protect itself, it raises the head very high. In this position, the jerk cannot be operated. If the rider tries it, the horse will get away at high speed and become unmanageable.

The horse's mouth is extremely sensitive, and needs, more than any other part, the study of the rider and the practice of the principle of strength of effects rather than effects of strength. Strength of effects means intelligence. Effects of strength mean jerk and saccade. Brutality belongs to the nature of an animal; but intelligence is the great gift of man. It is not by making the horse afraid of the bit that we make it understand the meaning of its effects. Only by the agreeable contact of the bit upon the bars, and by the sensitive repetition of this contact, does the horse come to understand, without fear, the fingering, the equestrian tact of its rider.

The first action of any animal, man included, on feeling pain in the mouth, is to shut it. But when a horse shuts its mouth forcibly on the bit, no mere two hundred pounds of human rider can pull it open by any effect of strength alone. But strength of effects, the taking and giving of the rider's hand, will release the tension and open the mouth, not because of any pain, but by a pleasant relaxing of the jaw. If along with this, the rider, by the effects of his legs, concentrates the animal's forces so as to bring the center of gravity under his seat, he establishes a control from which the animal cannot escape. But it is not by jerks and saccades that the horse comes to understand the effects of bits and legs.

Nevertheless, if the horse, taking contact with the bits, hesitates to yield the lower jaw, some vibration of the snaffle rein may be needed to relax the mouth. But vibrations and jerks are two different matters. The one is beneficial; the other is useless and dangerous.

CHAPTER XV

THE FIRST WORK MOUNTED: THE HANDS AND THE AIDS

All the work done up to this point has been merely preparatory. Now the time has come for the horse to be mounted, and for the whip to be replaced by the aids and effects of the rider's legs.

Other methodists, after completing the flexions and the mobilization on foot, pass directly to the flexions mounted. This I consider a serious error. To mount a young animal, and to keep it standing still during the time of its lesson on the various flexions, is to offer far too many occasions for nervous impatience and disorderly acts. Yet how is the rider to prevent these? The horse does not understand the aids. The effects of hands, legs, and seat are ignored. The rider is at the mercy of the animal's ignorance and caprice.

To meet this difficulty, I have for many years relied upon the following system:

As soon as the preparatory work on foot is completed, I mount the horse, and begin at once the training in the aids, before proceeding to the flexions standing still. First of all, I employ the legs, so that I may be able to push the horse forward against the contact of the bits. Not only do I continue my teaching of the aids of legs without spurs, at the beginning; I employ also spurs without rowels, for the sake of accustoming the horse to their use, to increase the effect of the legs, to accelerate the speed, and to obtain the contact of its jaw upon my hand. I am not satisfied with the walk only. I ask also the trot, since this is oftentimes a very great help in exercising and quieting the animal.

Only after the aids of the legs are well understood, so that I can always determine a free forward movement, do I proceed to the reversed pirouette, pirouette, and backing, for the mobilization of the fore hand, the hind hand, and the body as a whole. On the other hand, I begin the instruction of the front hand by the flexions mounted, while my control by my legs is still only partial, standing still, at walk, and at trot. Thus, without difficulty, restiveness, or rebellion, I arrive at the "in hand"; and finally, after more and more polishing, at the "assemblage."

Meanwhile, with the instruction of the horse, has progressed the tact of the cavalier in using his aids.

The various sorts of equitation employ many different means for directing and training the horse. The équitation raisonnée and the équitation savante admit only three aids—the hands, the legs, and the seat. Cavessons, whips, and martingales, chirruping with the tongue, caressings and punishments, are only means for helping the animal to comprehend the effects of these three.

Baucher in his method, though he includes the seat as an aid, gives no theory as to the relation of the seat to the assemblage; and his own position, always correct, is always and invariably perpendicularly above the center of gravity. Photographs of Fillis in action show alteration in his position which act upon the center of gravity in direct proportion to the movement involved. But only in a few of the movements explained in his method does he maintain the need of a proper inclination of the upper part of the man's body in the direction of the horse's motion.

The seat, simply as a means of staying on the horse's back at all gaits and movements, cannot be considered an aid, so long as the horse keeps to his merely instinctive equilibrium. But as soon as this instinctive equilibrium is replaced by the condition of transmitted equilibrium, then the effect of position of the rider's body, acting upon the center of gravity of the horse, becomes very powerful.

I discuss this better later on, after I have considered the theory of the assemblage, rassembler, and the state of collection. For the present, it is important for the student's understanding of the general idea of "accuracy of seat."

A second and more important aid is the hand. For this it makes no difference whether the horse is in instinctive or transmitted equilibrium. In either case, the effect of the reins passes to the mouth, from the mouth to the neck, from the neck to the front limbs, and from the fore hand throughout the entire animal mechanism. Baucher fully understood the importance of this aid, and created the flexions of mouth and neck. So too did Fillis, who was first to apply the expression doigter, that is to say, fingering.

The bridle hand can produce three general effects, which, in their turn, by the fingering and by the different positions of the hand, are still further modified in great variety.

The first is by tension of the reins, a retarding. Its opposite is freedom, permission, concession.

The second effect is by the steadiness of the bridle hand. Its immediate effect is sustension, and later elevation.

The third effect is by the position of the hand, to indicate the direction which the animal is to take.

These effects, in general, should be produced one after the other, but not simultaneously. To produce any one without at the same time producing any trace of any other, or disturbing the conditions involved in the other two, constitutes the "intelligent hand."

The usual position of the hand is that given above. But for control, training, or the like, the reins are carried upward, downward, backward, left or right, to an extent proportionate to the effect desired. During such movements the hand should always continue to feel the bit. When the hand has reached the position where it will obtain the required movement, it remains fixed in place until the movement is completed. Thus the motion of the hand conveys the nature of the movement; the fixation of the hand controls its execution.

CHAPTER XVI

THE LEGS AND THEIR EFFECTS

BY "legs" one means always the leg below the knee. The thighs remain always in permanent contact with the saddle, and always entirely independent of any movement or pressure of the calves. The common expressions of riding-teachers, "Close your legs," "Use your legs," "Fermez les jambes," refer, then, only to the free portion of the limb. They do not mean, as many beginners mistakenly suppose, that the horse's body is to be enveloped by the whole leg from hip to ankle!

The legs, including the feet, are the second mobile part of the rider's body and the most important means of controlling the horse. They and their effects are the essential promoters of every action of the horse, physical and moral. They must, therefore, act to just the right amount, neither too much nor too little; at just the right instant, neither before nor after, in accord with the fingering of the reins and the cadence of the stride; not interfering with the step, but reestablishing the tempo if lost; coordinated with the sensibility, nervousness, energy, or the lack of these, of the animal. The action of the legs demands, therefore, the highest "tact" on the part of the rider. Many are called, but few chosen to the proper management of this delicate and powerful aid.

To explain the effects of the legs and the causes of these, and to deduce from such general principles the correct manner of using these effects in practice, is the most complicated subject in all equestrian science.

In ancient times, before the invention of the bridle, the legs provided the only means of controlling the horse. Later came spurs. All the masters of equestrian art, from Xenophon to James Fillis inclusive, have laid down the principle that the effect of the contact of the legs is to impel the body forward in whatever direction is indicated by the reins.

This is, nevertheless, only partly true. When the legs are pressed against the flanks of an uneducated animal, their first effect is merely to tickle the panniculus carnosus muscle, which envelops the body from chest to haunch. But although this muscle does adhere to certain of the locomotor muscles, its action is entirely independent of the whole locomotor system. When, therefore, the horse feels the touch of a foreign object, it merely uses the panniculus carnosus to shake the skin, whether that foreign body be legs, spurs, or flies. It is, consequently, only as the result of education that the horse learns to support unmoved the rider's legs and spurs.

But below the panniculus carnosus, from thorax to pelvis, lie the great muscles which move the fore and hind limbs, and which are the principal agents in locomotion. Of these the latissimus dorsi carries the arm upward and backward, the longissimus dorsi, when it acts alone, is a powerful extensor of the vertebral column, and the deep pectoralis, attached at the angle of the shoulder, draws the whole fore limb backward. The student desiring to understand more fully the attachments, relations, and actions which are effected by pressure of the rider's legs, should consult some standard work on the anatomy of the horse.

It is, then, easy to understand that the rider's legs affect first of all the horse's hair, skin, panniculus carnosus, and abdominal tunic, all of which have nothing to do with locomotion; while the great pectoralis and its adjuncts, the latissimus dorsi, and the muscles of the haunches and hind limbs, are either affected only secondarily or remain unimpressed. But the first contact of the rider's legs is for the horse rather unpleasant than otherwise. It takes, therefore, patient teaching to accustom the untrained animal to endure this contact without anxiety, nervousness, or fear. Only after the horse, standing quiet and calm, supports the pressure of the legs on all parts of the body, from as far forward as the rider can reach to as far backward, has the time come for teaching the significance of this contact for the more important muscles of locomotion, such as the great pectoralis.

All masters of equitation have heretofore advocated putting the legs in contact with the horse's flanks and holding them there until the pupil makes one or two or more steps forward. I differ completely with this idea. The horse, standing, has all four limbs directly below its body. But in order for it to move forward, one of the fore legs, executing the three movements of the stride, must reach forward and come to the ground, ready to receive the weight. It thereupon becomes the fixed point upon which the great pectoralis acts to pull the body forward. But an acting muscle pulls one of its ends toward the other; not both ends toward the middle. If, then, the rider's two legs press equally upon the middle of the great pectoralis muscles, their natural action is prevented. All that the horse can then do is to stop; or if it be energetic or violent, to rear; or possibly to back, if the fixed point on which the muscles pull is the pelvis, the haunches, the ilium, or the loins. It is some improvement on the usual procedure gently to open and close the legs, making little repetitions of the contact. But even this is not completely satisfactory.

I advocate, therefore, this device. First, I make contact with both legs. Then, still keeping contact with one leg, with the other, very gently, I make and break contact, my leg never going more than half an inch out from the animal's body. Very soon, I see the fore leg on the same side take its forward stride, and at the same time I feel under me the opposite hind leg come off the ground. This is the first step! When one has obtained the first step, if he is a trainer, a master, he may feel sure that millions of steps will follow by and by. Now is the time to prove to your pupil, by caressings and rewards, that what he has done is what you asked. You have obtained the correct response, scientifically and naturally, without the quarrel, doubt, or confusion, which are the result of the wrong method of the old masters of equitation.

I dwell especially, at this point, on the importance of patience and moderation. Do not forget that you are an instructor, and that your pupil does not yet understand the meaning of your effects. Accept, therefore, your duty. Act as if you were dealing with a child who does not yet know the meaning of papa and mamma. Teach by kindness. Do not be violent. Do not kick the animal because it does not yet comprehend you. If you do, you will be sorry afterwards. Remember always that a horse, once properly educated, answers to the delicate and intelligent effects of your legs as it answers to the deftest fingering of your reins; and that all your domination of the animal is the product of your intelligence, a strength of effect, never, never, an effect of strength.

When, from standing, the horse will pass to the walk at the effects of the legs, without showing anxiety or haste, it should be taught by the same methods to pass from walk to trot, and from trot to gallop.

It is, however, one of the axioms of equitation that any effect of rider on horse loses its influence more and more the longer it is continued. If, then, bits or calves or spurs are employed continuously, without relaxation, the horse in time accepts the contact, becomes wonted to it, and all the effect disappears.

It is, therefore, necessary, from time to time, to "render the legs" in the same way that one renders the hand. Otherwise the sensibility to the pressure of the legs will wear away, or the hind hand will become fatigued and the horse refuse. But since the effect of the legs is less natural to the horse and less obvious to the rider than the effect of the hands, even more care must be taken to employ this effect with proper moderation. Moreover, if after obtaining motion forward by means of the contact of the legs, the rider continues to maintain the same contact as before, the horse will soon fail to understand the meaning of the first pressure. Relaxation of the contact is absolutely essential for conveying the meaning of the contact.

There are, however, two different ways of rendering the legs. Suppose that, to urge the horse forward, the rider needs three degrees of pressure. He exerts these three degrees, and the horse goes forward. The required speed being obtained, the legs then return to their normal one degree of contact, and the horse continues the movement for himself. This principle applies to all gaits and speeds.

There is, in addition, a second way of rendering the legs, which though unrecognized by the reasoned equitation, is far too much practiced—namely, the loss of all contact with the horse's flanks. To do this, one ought to be very sure of his seat, his horse, and his surroundings. Even then it is wiser to confine this meaning of the verb "to render " to occasions when the horse is standing still. Evidently, rendering the legs with the horse in motion, should not involve, at the same time, rendering the hands. One who does this is said to "abandon" his mount, a serious fault.

Thus far, for the sake of simplicity, I have spoken as if the effect of the rider's legs on the horse's body were the same, whatever the precise region of the contact. This is not, however, entirely the fact. There really are three different effects corresponding to three different positions.

Contact well forward near the girths tends to collect the horse and to aid the hand in establishing the state of equilibrium. This position tends also to keep the animal in equilibrium during movement.

Contact far back against the flank, on the other hand, tends to draw the hind legs forward under the center of gravity, and thus to favor stopping, or even going backwards.

The intermediate position between these two is the one which sends the horse forward, as already discussed.

These three different ways of using the legs, understood by both horse and man, will avoid certain mistakes on the part of both.

One more principle is to be noted. The action of one rein alone or of one leg alone has no meaning. The only effect that the horse can learn to understand is the additional or repeated effect of one rein or one leg while the other remains unmodified and uniform.

CHAPTER XVII

THE SPURS AND THEIR EFFECTS

SPURS had, at first, no rowels; but were stiletto-like and long. At that epoch, the bit, called buade, was very severe; and the saddle had high pommels before and behind. The rider's legs, therefore, extended straight down; and since he could not bend his knee, he needed the long spur to counteract the too powerful effect of the bit. Even to-day the Arabs still use this type of spur, called shabir.

But with the progress of equitation, effects of force have given way to force of effects, and the stiletto point has been superseded by rowels, severe, medium, or mild in proportion to the sharpness of their points. The choice of the right degree of severity of the rowels needed for any particular animal is governed by the creature's dullness or sensibility, and determined by the rider's equestrian tact. In any case, the horse has to be first accustomed to dull rowels and trained progressively to those more severe.

A great many sorts of rowel have been used, with various theories to explain their different forms. Practically, it is important to have the rowels turn loosely on their pivots. Otherwise, the horse's hairs may collect around them and prevent their turning at all. In that event, the points, being fixed, are a great deal more severe; and the rider may unwittingly spur much harder than he intends. Motion of the rowel from above downward is likewise more severe than in the reverse direction.