The Boy Travellers in the Russian Empire/Chapter 4

CHAPTER IV.

INSTEAD of returning to the hotel for dinner, our friends went to a traktir, or Russian restaurant, in a little street running out of Admiralty Square. The youths were anxious to try the national dishes of the country, and consequently they accepted with pleasure Doctor Bronson's suggestion relative to their dining-place.

"The finest and most characteristic restaurants of Russia are in Moscow rather than in St. Petersburg," said the Doctor, as he led the way to the establishment they had decided to patronize." St. Petersburg has a great many French and German features that you do not find in Moscow, and when we get to the latter city we must not fail to go to the 'Moskovski Traktir,' which is one of the most celebrated feeding-places of the old capital. There the waiters are clad in silk shirts, or frocks, extending nearly to the knee, over loose trousers of the same material. At the establishment where we are now going the dress is that of the ordinary French restaurant, and we shall have no difficulty in finding some one who speaks either French or German."

They found the lower room of the restaurant filled with men solacing themselves with tea, which they drank from glasses filled and refilled from pots standing before them. On each table was a steaming samovar to supply boiling water to the teapots as fast as they were emptied. The boys had seen the samovar at railway-stations and other places since their entrance into the Empire, but had not thus far enjoyed the opportunity of examining it.

"We will have a samovar to ourselves," said the Doctor, as they mounted the stairs to an upper room, "and then you can study it as closely as you like."

The Russian bill of fare was too much for the reading abilities of any one of the trio. The Doctor could spell out some of the words, but found they would get along better by appealing to one of the waiters. Under his guidance they succeeded very well, as we learn from Frank's account of the dinner.

"Doctor Bronson told us that cabbage soup was the national dish of the country, and so we ordered it, under the mysterious name of tschee e karsha. The cabbage is chopped, and then boiled till it falls into shreds; a piece of meat is cooked with it; the soup is seasoned with pepper and salt; and altogether the tschee (soup) is decidedly palatable. Karsha is barley thoroughly boiled, and then dried over the fire until the grains fall apart. A saucerful of this cooked barley is supplied to you along with the soup, and you eat them together. You may mingle the karsha with the

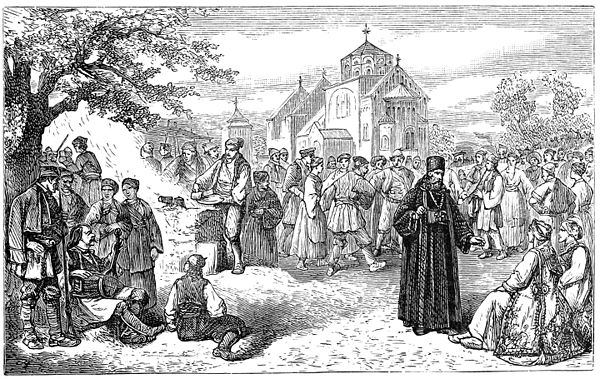

TEA-SELLERS IN THE STREETS.

tschee as you would mix rice with milk, but the orthodox way of eating is to take a small quantity of the karsha into your spoon each time before dipping it into the soup. A substantial meal can be made of these articles alone, and there are millions of the subjects of his Imperial Majesty the Czar who dine to-day and many other days in the year on nothing else. The Emperor eats tschee, and so does the peasant—probably the Emperor has it less often in the year than does his poor subject; but the soup is of the same kind, except that very often the peasant cannot afford the important addition of meat."

"Don't forget," Fred interposed, when the foregoing description was

RUSSIAN RESTAURANT AT THE PARIS EXPOSITION.

read to him—"don't forget to say that they served us a little cup or mug of sour cream along with the tschee."

"Yes, that's so," responded Frank; "but I didn't like it particularly, and therefore came near forgetting it. We remember best the things that please us."

"Then perhaps you didn't like the zakushka, or appetizer, before dinner," said the Doctor, "as I see you haven't mentioned it."

"I hadn't forgotten it," said the youth, "but was going to say something about it at the end. You know the preface of a book is always written after the rest of the volume has been completed, but as you've called attention to it, I'll dispose of it now. Here it is:

"There was a side-table, on which were several plates containing relishes of different kinds, such as caviare, raw herring, dried beef, smoked salmon cut in little strips or squares, radishes, cheese, butter, and tiny sandwiches about the size of a half-dollar. A glass of cordial, of which several kinds were offered, goes with the zakushka for those who like it; the cordial and a few morsels of the solid things are supposed to sharpen the appetite and prepare it for the dinner which is to be eaten at the table.

"The zakushka is inseparable from a dinner in Russia, and belongs to it just as much as do any of the dishes that are served after the seats are taken. While we were standing around the side-table where it was served at our first dinner in St. Petersburg, Doctor Bronson told us a story that is too good to be lost. I'll try to give it in his words:

"There was once a Russian soldier who had a phenomenal appetite; he could eat an incredible quantity of food at a sitting, and the officers of

AN OUT-DOOR TEA-PARTY.

his regiment used to make wagers with strangers about his feeding abilities. They generally won; and as the soldier always received a present when he had gained a bet, he exerted himself to the best of his ability.

"One day the colonel made a wager for a large amount that his man could eat an entire sheep at a sitting. The sheep was selected, slaughtered, and sent to a restaurant, and at the appointed time the colonel appeared with the soldier. In order to help the man along, the keeper of the restaurant had cooked the different parts of the sheep in various ways; there were broiled and fried cutlets, roasted and boiled quarters, and some stews and hashes made from the rest. Dish after dish disappeared. When almost the entire sheep had been devoured, the soldier turned to the colonel and said,

"'If you give me so much zakushka I'm afraid I sha'n't be able to eat all of the sheep when they bring it.'"

"But to return to soups. In addition to tschee, the Russians have ukha, or fish soup, made of any kind of fish that is in season. The most expensive is made from sterlet, a fish that is found only in the Volga, and sometimes sells for its weight in silver. We tried it one day, and liked it very much, but it costs too much for frequent eating except by the wealthy. A very good fish soup is made from trout, and another from perch.

"After the soup we had a pirog, or pie made of the spinal cord of the sturgeon cut into little pieces about half as large as a pea. It resembles isinglass in appearance and is very toothsome. The pie is baked in a deep dish, with two crusts, an upper and an under one. Doctor Bronson says the Russians make all kinds of fish into pies and patties, very much as we make meat pies at home. They sometimes put raisins in these pies—a practice which seems very incongruous to Americans and English. They also make solianka, a dish composed of fish and cabbage, and not at all bad when one is hungry; red or black pepper liberally applied is an improvement.

"What do you think of okroshka—a soup made of cold beer, with pieces of meat, cucumber, and red herrings floating in it along with bits of ice to keep it cool? Don't want any. Neither do we; but the Russians of the lower classes like it, and I have heard Russian gentlemen praise it. Many of them are fond of batvenia, which is a cold soup made in much the same way as okroshka, and about as unpalatable to us. We ordered a portion of okroshka just to see how it looked and tasted. One teaspoonful was enough for each of us, and batvenia we didn't try.

"After the pirog we had cutlets of chicken, and then roast mutton stuffed with buckwheat, both of them very good. They offered us some boiled pig served cold, with horseradish sauce, but we didn't try it; and then they brought roast grouse, with salted cucumbers for salad. We wound up with Nesselrode pudding, made of plum-pudding and ices, and not unknown in other countries. Then we had the samovar, which had been made ready for us, and drank some delicious tea which we prepared ourselves. Now for the samovar.

"Its name comes from two words which mean 'self-boiling;' and the samovar is nothing but an urn of brass or copper, with a cylinder in the centre, where a fire is made with charcoal. The water surrounds the cylinder, and is thus kept at the boiling-point, which the Russians claim is indispensable to the making of good tea. The beverage is drank not

from cups, but from glasses, and the number of glasses it will contain is the measure of a samovar. The Russians rarely put milk with their tea; the common people never do so, and the upper classes only when they have acquired the habit while abroad. They rarely dissolve sugar in their tea, but nibble from a lump after taking a swallow of the liquid. A peasant will make a single lump serve for four or five glasses of tea, and it is said to be an odd sensation for a stranger to hear the nibbling and grating of lumps of sugar when a party of Russians is engaged in tea-drinking.

PLANT FROM WHICH YELLOW TEA IS MADE.

"We sat late over the samovar, and then paid our bill and returned to the Square. Doctor Bronson told us that an enormous quantity of tea is consumed in Russia, but very little coffee. Formerly all the tea used in the Empire was brought overland from China by way of Siberia, and the business enabled the importers of tea to accumulate great fortunes. Down to 1860 only one cargo of tea annually was brought into Russia by sea, all the rest of the importation being through the town of Kiachta, on the frontier of Mongolia. Since 1860 the ports of the Empire have been opened to tea brought from China by water, and the trade of Kiachta has greatly diminished. But it is still very large, and long trains of sledges come every winter through Siberia laden with the tea which has been brought to Kiachta on the backs of camels from the districts where it is grown.

"There is one kind of the Chinese herb, called joltai chai (yellow tea), which is worth at retail about fifteen dollars a pound. It is said to be made from the blossom of the tea-plant, and is very difficult to find out of Russia, as all that is produced comes here for a market. We each had a cup of this tea to finish our dinner with, and nothing more delicious was ever served from a teapot. The infusion is a pale yellow, or straw-color, and to look at appears weak enough, but it is unsafe to take more than one cup if you do not wish to be kept awake all night. Its aroma fills the room when it is poured out. All the pens in the world cannot describe the song of the birds or the perfume of the flowers, and so my pen is unable to tell you about the aroma and taste of joltai chai. We'll get a small box of the best and send it home for you to try."

It was so late in the day when our friends had finished their dinner and returned to the Square, that there was not much time left for sight-seeing. They were in front of the Winter Palace and St. Isaac's Church, but decided to leave them until another day. Fred's attention was drawn to a tall column between the Winter Palace and a crescent of lofty buildings called the État-major, or staff headquarters, and he asked the Doctor what it was.

"That is the Alexander Column," was the reply to the question. "It is one of the largest monoliths or single shafts of modern times, and was erected in 1832 in memory of Alexander I."

"What a splendid column!" said Frank. "I wonder how high it is."

COLUMN IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER I.

Thereupon the youths fell to guessing at the height of the column. After they had made their estimates—neither of them near the mark but considerably below it—Doctor Bronson gave them its dimensions.

"The shaft, without pedestal or capital, is fourteen feet in diameter and eighty-four feet high; it was originally one hundred and two feet high, but was reduced through fear that its length was out of proportion to its diameter. The base and pedestal are one single block of red granite about twenty-five feet high, and the capital is sixteen feet high. The angel above the capital is fourteen feet tall, and the cross in the hands of the angel is seven feet above it. With the platform on which it rests, the whole structure rises one hundred and fifty-four feet from the level of the ground."

"They must have had a hard time to make the foundations in this marshy ground," one of the boys remarked.

"They drove six rows of piling there, one after the other, before getting a foundation to suit them," said the Doctor. "The shaft alone, which was put up in the rough and finished afterwards, is thought to weigh about four hundred tons, and the pedestal and base nearly as much more. Unfortunately the shaft has suffered from the effects of the severe climate, and may be destroyed at no distant day. Several cracks have been made by the frost, and though they have been carefully cemented, they continue to increase in size. Pieces have fallen from the surface of the stone in the same way that they have fallen from the Egyptian obelisk in New York, and it is very evident that the climate of St. Petersburg is unfriendly to monuments of granite."

The bronze on the pedestal and capital is from Turkish cannon which were melted down for the purpose. The only inscription is in the few words,

"TO ALEXANDER THE FIRST, GRATEFUL RUSSIA."

Frank made a sketch of the monument together with the buildings of the État-major and a company of soldiers that marched past the foot of the column. Doctor Bronson said the soldiers belonged to the guard of the palace, where they had been on duty through the day, and had just been relieved.

From the column and the buildings surrounding it the trio of strangers walked to the bank of the river and watched the boats on the water, where the setting sun slanted in long rays and filled the air with the mellow light peculiar to high latitudes near the close of day. It was early in September, and already the evening air had a touch of coolness about it. St. Petersburg is in latitude 60° North, and consequently is quite near the Arctic Circle. Doctor Bronson told the youths that if they had come there in July they would have found very little night, the sun setting not far from ten o'clock and rising about two. In the four hours of night there is almost continuous twilight; and by mounting to the top of a high building at midnight one can see the position of the sun below the northern horizon. Any one who goes to bed after sunset and rises before sunrise would have very little sleep in St. Petersburg in summer.

"On the other hand," said the Doctor," the nights of winter are very

PETER THE GREAT.

long. Winter is the gay season here, as the city is deserted by fashionable people in summer, and one is not expected to make visits. The Imperial court goes away; the Emperor has a palace at Yalta in the Crimea, and there he passes the autumn months, unless kept in St. Petersburg or Moscow by the affairs of the nation. They have some public festivities here in summer, but not generally, most of the matters of this kind being reserved for the winter."

Boats were moving in all directions on the placid waters of the river, darting beneath the magnificent bridge that stretches across the stream, and carrying little parties, who sought recreation or were on errands of business. On the opposite side of the Neva, and beyond the Winter Palace, was the grim fortress of Sts. Peter and Paul, with whose history many tales of horror are connected, and where numerous prisoners of greater or less note have been confined. "It was there," said Doctor Bronson, "that Peter the Great caused his son Alexis to be put to death."

"Caused his son to be put to death!" exclaimed the youths together.

"Yes, it is generally believed that such was the case," the Doctor answered, "though the fact is not actually known. Alexis, the son of Peter the Great, was opposed to his father's reforms, and devotedly attached to the old superstitions and customs of Russia. Peter decided to exclude him from the throne; the son consented, and announced his desire to enter a monastery, from which he managed to escape to Austria, where he sought the protection of the Emperor of that country. Peter sent one of his generals in pursuit of Alexis; by a combination of threats and promises he was induced to return to St. Petersburg, where he was thrown into prison, and afterwards tried for high-treason and condemned to death. Peter pardoned but did not release him. On the 7th of July, 1718, he died suddenly, and it was and is now generally believed that he was poisoned or beheaded by his father's order."

"And was he really guilty of high-treason?" Fred asked.

"According to Russian law and custom, and particularly according to the law and custom of Peter the Great, he certainly was," Doctor Bronson replied. "Remember, the Emperor is autocratic in his power, at least in theory, and in Peter's time he was so actually. The will of the founder of the Russian Empire was law; Alexis was opposed to that will, and consequently opposed to the Imperial law. The progress of Russia was more in the eyes of Peter than the life of any human being, not even excepting his own son, and the legitimate heir to the throne. The proceedings of the trial were published by Peter as a justification of his act.

"Peter II., the son of Alexis and grandson of the great Peter, died suddenly, at the age of fifteen; Peter III., grandchild of Peter the Great through his daughter Anna, was the husband of the Empress Catherine II.; but his reign was very short. His life with Catherine was not the happiest in the world, and in less than eight months after he became Emperor she usurped the throne, deposed her husband, and caused him to be strangled. Catherine was a German princess, but declared herself thoroughly Russian when she came to reside in the Empire. If history is correct, she made a better ruler than the man she put aside, but this can be no justification of her means of attaining power.

"Her son, Paul I., followed the fate of his father in being assassinated, but it was not by her orders. She brought him up in complete ignorance

ASSASSINATION OF PETER III.

of public affairs, and compelled him to live away from the Imperial court. Until her death, in 1796, she kept him in retirement, although she had his sons taken to court and educated under her immediate supervision. Treatment like this was calculated to make him whimsical and revengeful, and when he became emperor he tried to undo every act of his mother and those about her. He disbanded her armies, made peace with the countries with which she was at war, reversed her policy in everything, and became a most bitter tyrant towards his own people. He issued absurd orders, and at length his acts bordered on insanity.

"A conspiracy was formed among some of the noblemen, who presented to his son Alexander that it was necessary to secure the abdication of his father on the ground of incapacity. Late at night, March 23d, 1801, they went to his bedroom and presented a paper for Him to sign. He refused, and was then strangled by the conspirators. Alexander I.

PAUL I.

was proclaimed emperor, and the announcement of Paul's death was hailed with delight by his oppressed subjects. Among the foolish edicts he issued was one which forbade the wearing of round hats. Within an hour after his death became known, great numbers of round hats were to be seen on the streets.

"You've had enough of the history of the Imperial family of Russia for the present," said the Doctor, after a pause, "and now we'll look at the people on the streets. It is getting late, and we'll go to the hotel, making our observations on the way.

"Here are distinct types of the inhabitants of the Empire," the Doctor remarked, as they passed two men who seemed to be in animated conversation. "The man with the round cap and long coat is a Russian peasant, while the one with the hood over his head and falling down to his shoulders is a Finn, or native of Finland."

"How far is it from here to Finland?" Frank asked.

"Only over the river," the Doctor replied. "You cross the Neva to its opposite bank, and you are in what was once the independent duchy of Finland, but has long been incorporated with Russia. When Peter the Great came here he did not like to be so near a foreign country, and so made up his mind to convert Finland into Russian territory. The independence of the duchy was maintained for some time, but in the early part of the present century Russia defeated the armies of Finland, and the country was permanently occupied. Finland has its constitution, which is based on that of Sweden, and when it was united with Russia the constitutional rights of the people were guaranteed. The country is ruled by a governor-general, who is appointed by Russia; it has a parliament for

RUSSIAN AND FINN.

presenting the grievances and wishes of the people, but all acts must receive the approval of the Imperial Government before they can become the law of the land."

"What are those men standing in front of a building?" said Fred, as he pointed to a fellow with a broom talking with another in uniform.

"The one in uniform is a postman," was the reply, "and the other is a dvornik, or house guardian. The dvornik sweeps the sidewalk in front of a house and looks after the entrance; he corresponds to the porter, or portier, of other countries, and is supposed to know the names of all the tenants of the building. The postman is reading an address on a letter, and the dvornik is probably pointing in the direction of the room occupied by the person to whom the missive belongs."

"I have read that letters in Russia are examined by the police before they are delivered," said one of the boys. "Is that really the case?"

"Formerly it was, or at least they were liable to examination, and it probably happens often enough at the present time. If a man is suspected of treasonable practices his correspondence is liable to be seized; unless there is a serious charge against him, it is not detained after examination, provided it contains nothing objectionable. The Post-office, like everything else in Russia, is a part of the military system, and if the Government wishes to do anything with the letters of its subjects it generally does it. The correspondence of foreigners is rarely meddled with. Writers for the foreign newspapers sometimes complain that their letters are lost in the mails, or show signs of having been opened, but I fancy that these cases are rare. For one, I haven't the least fear that our letters will be troubled, as we have no designs upon Russia other than to see it. If we were plotting treason, or had communications with Russian and Polish revolutionists in France or Switzerland, it is probable that the Government would not be long in finding it out."

"What would happen to us, supposing that to be the case?" Frank inquired.

"Supposing it to be so for the sake of argument," the Doctor answered, "our treatment would depend much upon the circumstances. If we were Russians, we should probably be arrested and imprisoned; but as we are foreigners, we should be asked to leave the country. Unless the matter is very serious, the authorities do not like to meddle with foreigners in any way that will lead to a dispute with another government, and their quickest way out of the difficulty is to expel the obnoxious visitor."

"How would they go to work to expel us?"

"An officer would call at our lodgings and tell us our passports were ready for our departure. He would probably say that the train for the frontier leaves at 11 a.m. to-morrow, and he would expect us to go by that train. If the case was urgent, he would probably tell us we must go by that train, and he would be at the hotel at ten o'clock to escort us to it. He would take us to the train and accompany us to the frontier, where he would gracefully say good-by, and wish us a pleasant journey to our homes. If matters were less serious, he would allow us two or three days, perhaps a week, to close our affairs; all would depend upon his orders, and whatever they were they would be carried out.

LODGINGS AT THE FRONTIER.

"Before the days of the railways objectionable parties were taken to the frontier in carriages or sleighs, the Government paying the expense of the posting; and no matter what the hour of arrival at the boundary, they were set down and left to take care of themselves. An Englishman who had got himself into trouble with the Government in the time of the Emperor Nicholas, tells how he was dropped just over the boundary in Prussia in the middle of a dark and rainy night, and left standing in the road with his baggage, fully a mile from any house. The officer who accompanied him was ordered to escort him over the frontier, and did it exactly. Probably his passenger was a trifle obstinate, or he would not have been left in such a plight. A little politeness, and possibly a few shillings in money, would have induced the officer to bring him to the boundary in the daytime, and in the neighborhood of a habitation.

"Expelled foreigners have rarely any cause to complain of the incivility of their escorts. I know a Frenchman who was thus taken to the frontier after a notice of two days, and he told me that he could not have received greater civility if he had been the guest of the Emperor, and going to St. Petersburg instead of from it. He added that he tried to outdo his guardians in politeness, and further admitted that he richly deserved expulsion, as he had gone to the Empire on a revolutionary mission. On the whole, he considered himself fortunate to have escaped so easily."

The conversation led to anecdotes about the police system of Russia, and at their termination our friends found themselves at the door of the hotel. Naturally, they shifted to other topics as soon as they were in the presence of others. It was an invariable rule of our friends not to discuss in the hearing of any one else the politics of the countries they were visiting.

ORDERED TO LEAVE RUSSIA.