The Development of Navies During the Last Half-Century/Chapter 2

CHAPTER II

CREATION OF A STEAM FLEET

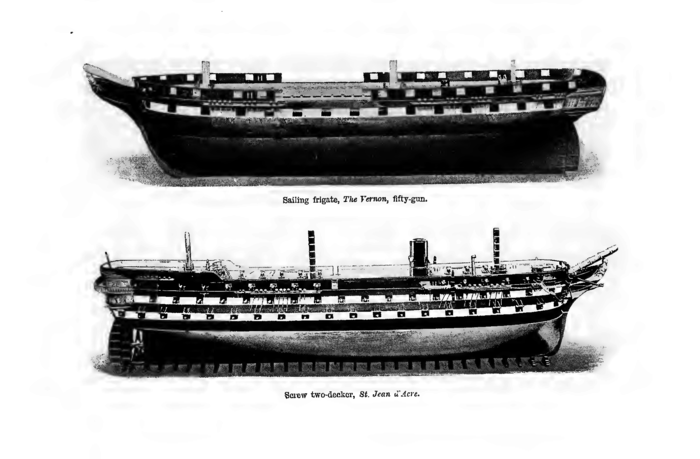

Changes in Ship Construction after 1840—Reluctance to recognise Advantages of Screw Propulsion—Gradual Conversion of Sailing Fleet to Steam—Armament practically remains unaltered—The Crimean War—Operations in Black Sea and Baltic—Assistance rendered by the Navy—Expedition to Sea of Azof.

This led to the construction over here of the 'Orlando' and ’Mersey,' the largest frigates built entirely of wood, and launched in 1858. Their length was 300 ft, beam 52 ft, and burthen 3750 tons. They were, however, structurally weak, and did not last long. The 68-pounder was still the heaviest gun carried, for we had not yet arrived at rifle guns. Shell equipment was now universally provided, for Sinope had convinced even the strongest adherents of solid shot that whatever might be the advantages of the latter against stone walls in their smashing effect, shell for the attack of ships must prevail. Appliances for the use of red-hot shot were still supplied. These projectiles were formidable to wooden ships. Nelson considered fire the greatest danger of a naval battle. Before going into action it was the custom, as far as possible, to remove everything below which might feed a fire. But there was danger also to the ship using red-hot shot. Guns occasionally burst owing to the expansion of the projectile, for which provision had to be made in the diameter of the bore. There might also be a premature discharge by the ignition of the powder. To prevent this, thick junk wads were supplied for use with hot shot, to be well soaked in water and then rammed down after the powder, thus interposing a screen between the charge and shot.

Rockets were another species of weapon much favoured then, but which have recently ceased to form part of our ships' equipment. They were also for incendiary purposes, and proved very effective against savage races and bodies of men. They were first introduced, early in the century, by Sir William Congreve. Their flight was produced by the escape of the gas to the rear, generated by the ignited explosive, and steadiness was imparted by attaching a wooden rod to the case. The use of the rod was dispensed with by the invention of Mr Hale, who caused the rocket to rotate in its flight. This was effected by the gas in its escape impinging on short iron wings at the end of the case, thus imparting rotatory motion. Rockets, however, for war purposes were not to be depended on, especially after being kept for some time, and occasionally they gave rise to serious accidents.

Before passing on to the great change which the adoption of iron as a material for ship building and as a means of protection produced in our fleet, it seems desirable to review briefly the operations in the Black Sea and Baltic during the Crimean War, when we had for the last time sailing ships combined with screw and paddle steamers. These operations afford an example of the effect of a powerful navy in rendering possible military operations in distant lands, and aiding them in many ways. Our success at Acre is not repeated in a bombardment of land batteries under different conditions in one locality, whereas it is shown elsewhere that if special plant is provided such an operation can be undertaken without great risk. This war, from a naval point of view, has many striking features. It is difficult to realise now how little prepared we were in 1853 for war with a powerful continental nation, and for such an operation as the invasion of its territory. Though the Naval Department has generally been assumed to have emerged from that war with more credit as regards its organisation than the War Oflfice, the term 'mobilisation,' and its meaning, was entirely unknown in reference to any possible naval operation. If success has come in the past, it has been in spite of our system, not in consequence of it.

For instance, previously to the Crimean War there had been a Transport Department at the Admiralty, but a regard for economy had led to its suppression. Nevertheless, when it was reorganised, energy and ability supplied the want of experience. Its operations were on a large scale, for we conveyed to the east 70,000 officers and men, 5600 horses, and 85,000 tons of stores. To the Baltic, also, we transported 13,000 officers and men, with about 10,000 tons of stores. It must be remembered that our allies looked to us in a great measure for transport. Though steam propulsion was in its infancy, we employed over 100 steam transports, and a slightly greater number of sailing ships. Sir Stafford Northcote, in a letter to Mr Disraeli, dated April 19th, 1862, and printed in his life, says: 'We showed in the Crimean War both our weakness and our strength. Our strength consisted in the elasticity of our resources, the temper of our people, the length of our purse, and the power of our endurance. Our weakness was shown in the confusion of our arrangements and the absence of military skill.' But he might have added that the chief evidence of our strength was to be found in our maritime supremacy, which made such an expedition possible. History has not adequately recorded the part played by the navy on this occasion, because there were no fleets to overcome, and it did not repeat the success at Acre; but in other ways the assistance it rendered was of the utmost importance.

In command of the Mediterranean Squadron at that time was Admiral Deans Dundas. He was an officer who had seen much service, but had now reached the age of sixty-eight, and owing to a former wound could not sustain great exertion. When he was appointed to this command, it was not anticipated that we should shortly be involved in war. As second in command of the squadron we had in Sir Edmund Lyons a man of great ability and energy. His early career had been a distinguished one, but in 1835 he was appointed Minister at Athens, a post he filled for several years, so that in 1854 his capacity for naval affairs was not well known in the fleet. Detailed by Admiral Dundas to organise arrangements for transporting the army from Varna to the Crimea, he at once gave proof of his capability. All difficulties disappeared before his energy and gift for organisation. Yet it was no easy task to shift the base of operations from Turkey to Russia. To forward 60,000 troops from England and France had taxed the resources of those countries, but to tranship them on the barren shores of the Black Sea entailed a greater call on those entrusted with the operation. Much had to be created on the spot; yet although the order to invade the Crimea only reached Lord Raglan on July 6th, 1854, the combined armies, with their necessary equipment, embarked on August 24th. Circumstances delayed their sailing till September 7th, when they set forth for the enemy's country. What a splendid sight it must have been, over 150 vessels conveying the troops, guarded and convoyed by a British squadron of ten sail of the line and fifteen smaller vessels. The French men-of-war were filled with troops owing to insufficiency of transports. What a time for an enterprising enemy to make a dash at this armada! Inside the harbour of Sebastopol there was a powerful flotilla, consisting of thirteen sail of the line and sixteen smaller vessels. A determined attack might have scattered that cloud of transports, and, taking into consideration the time of year, indefinitely postponed the expedition. But the opportunity was lost, and 63,000 men, with 128 guns, were landed without opposition, as if for some peaceful autumn manoeuvres. As an operation of war it was hazardous. A night assault on our force after landing might have been disastrous. None took place, and the battle of the Alma strengthened our position in the occupied territory. It was then decided to invest the south side of Sebastopol, while the navy were to occupy the port of Balaclava as a base of operations for the army. From a naval point of view this harbour was well suited to the purpose. Though not of great extent, it contained deep water, and had facilities for landing stores. Moreover, the anchorage was well sheltered from all winds, and as at this time it was not considered that the siege would prove a lengthy operation, I am unable to see that the choice of Balaclava was a bad one.[1]

The arrival of the army at the head of Balaclava Harbour and the entry of our ships took place simultaneously on the 26th of September. To this no resistance was offered by the enemy, and the siege train was landed next day. By the act of the Russians in sinking most of their largest ships across the entrance to Sebastopol our naval force was freed from any thought of having to meet the enemy at sea. What a blow to those gallant Russian sailors, who afterwards took such a distinguished part in the siege, to see a fleet it had taken years to construct settling down in the water without a combat. Though the foe was a combination of the two most powerful maritime nations of Europe, they were ready for the fray, and the disappointment could not be otherwise than bitter. England had experienced such a day of humiliation two centuries before when she scuttled her own vessels to bar the passage of the Dutch up the Medway, and then vainly turned to forts as a substitute for an efficient fleet.

But our squadron in the Black Sea was able to afford material assistance in other ways towards the object aimed at, the capture of Sebastopol. Over sixty guns were landed from the ships, and a naval brigade formed of 2000 officers and men. This greatly augmented the resources of the allied armies in preparing for the first bombardment of the Russian works defending the southern side of the town. This took place on the 17th of October, and in order to assist the operation the admirals of the English and French Squadrons were requested to attack simultaneously the sea defences. When I use the word 'requested,' it is perhaps hardly applicable to the French naval commander. He was under the orders of the general in command, and hence to such a direction could only demur on strong grounds. In our case the admiral was acting independently, and though he would naturally afford the general the fullest co-operation, he was at liberty to withhold his consent to any course of action as regards the fleet which might to him seem undesirable. Admiral Dundas was reluctant to expose his ships to damage in an attack which, according to his judgment, would have no direct influence upon the assault by land. It must be remembered, moreover, that he had willingly denuded his vessels of a portion of their armament, and reduced their crews by a considerable number; and he might have insisted that a sea attack should only be undertaken with ships fully equipped. But when his French colleague informed him of his intention to carry out the desire of his general, with or without our assistance, Admiral Dundas felt compelled to join in the attack.

The forts which the combined squadrons were about to bombard defended the approach to the harbour of Sebastopol. On the north side, to which our ships were allotted, they were especially strong. At the entrance was Fort Constantine, a massive stone structure mounting 100 guns. But still more formidable to ships were the batteries on the high ground above, which, though not armed with numerous guns, could sweep the sea beneath with comparative impunity. The southern side was defended by a battery at the mouth of Quarantine Bay, and Fort Alexander further in. The French Squadron was to attack on this side, and with our vessels form a continuous line in front of the harbour. It had been arranged that fire on land and sea should be opened early in the morning; but at the last moment this was altered as regards the ships, and they did not commence until after one o'clock. By this time all idea of a land assault had been given up owing to the discomfiture of the French batteries on shore. More than one explosion had taken place in their lines, and they were not prepared to join us in the intended movement which was to follow a vigorous cannonade. The ships, however, proceeded to carry out their part of the day's work. Sir Edmund Lyons, in the 'Agamemnon,' with the 'Sanspareil,' 'London,' 'Albion,' and 'Arethusa,' formed an inshore squadron, and anchored within 800 yards of the northern batteries, while the rest of our ships were further off, prolonging the French line. Fire was then opened on both sides. Considerable impression was made on Fort Constantine, but the batteries on the cliff, when they got the range of our ships, subjected them to an effective fire to which little return could be made. The 'Rodney,' 'Queen,' and 'Bellerophon' then closed to reinforce the hardly pressed inshore squadron, and the cannonade was continued. Owing to the fact that most of the ships had landed their upper deck guns, and that this portion was comparatively clear of men, our casualties were not so numerous as they otherwise would have been. The Russians used chiefly time fuses with their shell, numbers of which burst over the upper decks, cutting them up like a ploughed field. But, nevertheless, at the close of day, when our vessels withdrew from their positions, we had lost over forty killed, and 250 men wounded. The French had an easier task, and did not suffer so severely. The gain was not commensurate with such a loss, and in fact the whole proceeding was unwise. If the object was to facilitate the assault and entry of our troops on the south side, it is difficult to see what benefit would accrue from shelling batteries in another quarter. When this assault was postponed, there was clearly no reason to attempt the destruction of works intended to resist entry by sea, and which could have little influence upon an army taking the city in rear.

From a naval point of view, however, the principal lesson taught by this episode is the strength exhibited by a few guns on high ground even when opposed by a powerful squadron. Fort Constantine must have succumbed in time, even as the forts at Acre were unable to withstand the heavy and rapid fire of our ships. But a single elevated battery is difficult to silence, and may defy the efforts of a fleet. This was perfectly well understood in the old wars, but the lesson had been forgotten, until it was once more brought home to us on this memorable occasion. Another point demonstrated was the disadvantage attached to joint enterprises under dual command. Of this we had not much previous experience, because in most of our struggles at sea we had fought single-handed. But the Franco-Spanish alliance, which was punished at Trafalgar, is an example of the doubtful strength of such combinations. How bitterly Villeneuve complained of his Spanish colleagues. No plans could be formed that were not liable to be disturbed by their different methods of business and organisation. One supreme chief is necessary to success, and should we ever engage in any maritime alliance again, there must be one head, recognised by both States, and invested with full authority over the whole force.

A more profitable service rendered by the navy in the Crimea was in cutting off communications with Sebastopol by the Sea of Azof. In February 1855, about six weeks after Sir Edmund Lyons assumed chief command of the Black Sea fleet, Admiral Dundas having gone home, the Admiralty called his attention to the importance of occupying as soon as possible the Sea of Azof, as the Russian army in the Crimea drew largely both reinforcements of men and supplies of provisions conveyed by water between Rostof and Taganrog and the shores of the Crimea bordering on the Sea of Azof. Such an enterprise accorded with the energetic spirit of the admiral, and in conjunction with our allies an expedition was organised for this service. The entrance to this inland sea is commanded by the powerful fort of Kertch, and to take this in rear a strong landing force was provided. This consisted of 7000 French, 3000 English, and 5000 Turkish troops. They were conveyed in nine sail of the line and forty smaller vessels. The expedition started on the 22d of May, and arrived in the vicinity of Kertch the next day. A bay within ten miles of this town was selected, and disembarkation was effected without delay or obstruction. Baron Wrangel, the Russian general in command of this portion of the peninsula, did not oppose the landing. In fact, he could not tell where it might take place, and was unable to move troops as fast as ours could be conveyed by sea. Fearing to be cut off from Scbastopol, he destroyed several batteries on the coast and retired. As Kinglake eloquently says of the incident: 'He (Baron Wrangel) succumbed to the power (of which the world will learn much in times to come) an armada can wield when not only carrying on board a force designed for land service, but enabled to move swiftly, whether this way or that, at the will of the chief.' Kertch was occupied on the 24th of May, and Sir Edmund Lyons, hoisting his flag on board the 'Miranda,' entered the Sea of Azof. He then placed a squadron of light draught vessels under the orders of his son, Captain E. M. Lyons, consisting of fourteen sloops and gun vessels, with five French steamers. Holding commands in this squadron were some of the ablest men our navy possessed. Such names as Commerell, Sherard Osborn, Cowper Coles, Hewett, M'Killop, Burgoyne, and others, were a guarantee that activity in this quarter, at least, would prevail. Events succeeded each other rapidly. On May 26th the squadron appeared off Berdiansk, where the enemy burnt four war steamers of his own and large depots of corn. On the 27th Arabat was bombarded, and in three days 106 merchant vessels were destroyed. The same activity continued until the operations closed in November by reason of approaching winter. A volume might be written of the work done in this region by the navy. It has never been adequately recorded, but the cutting off and destruction of all the sources of supply to the Russian army from the Sea of Azof contributed in no small or unimportant degree to the fall of Sebastopol.

Although, as I have endeavoured to show, the naval operations in the Black Sea afforded invaluable assistance to the Crimean expedition, it was to the Baltic squadron that the nation looked for the greatest triumphs on the sea. These expectations were not destined to be realised by any great feat of arms. For this there were many reasons, the principal one being that the means were not adapted to the end, and that there was no clear conception as to what the fleet could be reasonably expected to perform.

When, in the early part of February 1854, it was seen that war could not be avoided, every exertion was made to fit out a formidable Baltic Squadron. Of the ships detailed to form this squadron some were at Lisbon, while others were laid up in the various home ports. It had been usual to offer a bounty to seamen to ship afloat when required on an emergency, but in this case it was not done, and all sorts and conditions of men were entered to complete the complements of the ships. By this means a squadron was collected with what was considered at that time creditable expedition. Admiral Sir Charles Napier was selected for the command, whose reputation in the country was still high, though he was now sixty-eight years of age. The squadron, having assembled at Portsmouth, left on the 12th of March, Her Majesty leading it to sea in her screw yacht the 'Fairy.' On that day the force consisted of eight ships of the line, four frigates, and three paddle steamers. Other ships not yet complete with crews had to be left behind, and joined afterwards. Bound for the Baltic, where the water all round the coast is very shallow, vessels of light draught for certain operations were an essential adjunct to such a force; but no gunboats had been provided. This omission strongly influenced the course of events.

On March 27th the fleet anchored in what was then the Danish port of Kiel. Our first object was to confine the enemy's vessels to the Baltic, so that their power of offensive action against our coasts and commerce might be neutralised. A blockade was therefore essential. A trial of strength between the two fleets was also desirable, as success in such an action would secure the same end more effectually. Attack on strong fortresses was deprecated as likely to damage the fleet without an adequate return. The nation, however, expected an attack on Cronstadt, no doubt with the recollection of Acre in its mind. But the conditions were very different. Not that the sea defences of Cronstadt at the declaration of war were of the formidable nature attributed to them, but because the neighbouring water was so shallow that the approach of large ships was a difficult matter. The want of gunboats capable of taking up advantageous positions within range of the forts was the reason given by Sir Charles Napier for abstaining from an attack on Cronstadt. He was unwilling to risk injury to his own squadron by such an operation while the Russian fleet was intact. It was no secret at Acre that he opposed the bombardment as most hazardous, but orders from England were imperative on that occasion. In the Baltic many of the ships were most indifferently manned, and kept the sea with difficulty. We were unable to prevent a junction between the Russian Squadrons at Sveaborg and Cronstadt, the former getting out when a gale of wind had driven our squadron of observation from the port. But a younger and more energetic commander would probably not have been so much impressed with the risks incurred; and Nelson in his daring exploit at Copenhagen undertook a task of equal magnitude without hesitation.

Sir Charles Napier having set his face against a direct attack on Cronstadt or Sveaborg—another place where powerful land batteries guarded the sea approaches—turned his attention to Bomarsund, the stronghold of the Aland Islands. It was guarded by forts mounting numerous heavy guns, with a garrison of 2500 men. No reinforcement was possible while our ships commanded the water intervening between these islands and the mainland. Hence the safest and most certain form of attack was to land a sufficient force at a convenient spot and take the forts in rear. This was decided upon, and the British admiral desired to effect it with the resources of the combined squadron alone, but the French commander considered them insufficient, and a body of 9000 French troops was sent out arriving early in August. When all was ready, guns and men were landed without opposition. Besides the regular troops, a large contingent of sailors and a battery of 32-pounders from the ships formed part of the force. Works were then thrown up within range of the forts, and between the 13th and 15th the forts were bombarded. One after another surrendered, until the whole of Bomarsund was ours. In default of relief from the sea, capitulation was inevitable. This incident is an excellent example of the power conferred by command of the sea when at the same time there is a sufficient land force judiciously employed.

No other operation of any magnitude was attempted that year, and when the Baltic Squadron returned to England for the winter it was not considered to have put forth its full strength. There was much criticism on the decision not to attack Sveaborg, so a new commander-in-chief, Rear-Admiral the Hon. R. Dundas, with a stronger squadron, was sent up the following year. By this time gunboats and mortar vessels had been prepared, and the crews of the squadron had much improved, so that the new admiral started under fair auspices, Her Majesty Again leading the squadron to sea and wishing it success. In the beginning of August the whole flotilla approached Sveaborg. The gun vessels and mortar boats were to perform the principal part in the bombardment. The fortress consisted of five islands, on which were batteries with numerous heavy guns. On the 9th of August the attack took place. Carefully assigned positions were taken up by our small vessels—the remainder of the fleet being in rear—and a heavy fire opened on the defences. The gun and mortar boats offered so small a mark and were at such a range that the return fire from the shore did comparatively little damage. After some hours our shells blew up more than one magazine and set fire to several buildings. At sunset the gunboats were withdrawn, but the place was plied with rockets during the night. During the next day the attack was continued. The whole place now seemed a sheet of flame, and on the morning of the 11th, the enemy's batteries having ceased to reply to our guns, the action was discontinued. On our side only a few men were wounded, but the Russians lost considerably. Though the fortress was much knocked about, a few days would have put it in a condition to sustain another bombardment; and whether it surrendered or not, we were unable to land a sufficient force for its occupation. We had, however, shown that a powerful fortress could be attacked from the sea, and without great loss, if undertaken with plant adapted to the purpose. It was simply a question of providing sufficient material, and keeping up the supply until the object was attained. Success would rest with that side which possessed the longest purse and the greater resources. With an absolute command of the sea, the impregnability of a fortress becomes a comparative term, and another year of war would doubtless have seen a similar attack on Cronstadt. But Sebastopol now fell, and peace was made.

This war produced no naval actions or single combats between ships, but maritime strength had in other ways brought about a result even greater than could have been secured by a great naval victory. The voluntary sinking of a large portion of the enemy's fleet, the inaction of another part, the invasion of territory, the reduction of some fortresses, and the total stoppage of sea commerce, were directly or indirectly owing to naval supremacy tacitly acknowledged. Steam had materially assisted the attack, while it conferred no advantage on the defence. As Kinglake eloquently says of the result of the Kertch expedition: 'The simple truth is that, in regions where land and sea much intertwine, an armada having on board it no more than a few thousand troops, and propelled by steam power, can use its amphibious strength with a wondrously cogent effect.'

- ↑ Sir Edward Hamley, in his interesting volume The War in the Crimea, states that the choice of Balaclava as a base brought untold miseries upon the army, and speaks strongly of the influence Sir Edmund Lyons had with Lord Raglan. But the point the admiral had to consider was, whether Balaclava was suitable to receive transports and store ships, and whether the harbour offered facilities for discharging cargo? He could assure the general that no delay should take place in these respects. The proof of this lies in the fact that the siege train was landed the day after the harbour was entered. As to the distance of the harbour from our camp, that was a matter which the general would weigh in deciding whether to accept or reject the admiral's recommendation. It did not affect the suitability of the port for getting the stores on shore; their prompt transport to the camp rested with the Military Department. If the land transport arrangements were faulty, and want of men prevented good roads from the base to the camp being made until after the battle of Inkerman, the difficulties that resulted are not attributable to any deficiency of Balaclava as a naval port. I regret that the gallant author of this work should speak of Sir Edmund Lyons as Lord Raglan's evil genius. The mind of the admiral was wholly absorbed by the desire to render every assistance to his comrades on shore, and he brought to this work an energy, ability, and single-mindedness which, hardly realised in the past, will some day, I am sure, receive ample recognition.