CHAPTER IV.

ORIGINATING CAUSES OF THE SEPOY REBELLION.

WHILE moving amid the gorgeous scenes of the previous chapter, we were happily unconscious of the circumstances of danger by which we were surrounded, and which could so easily have victimized us all. We knew not then of that peculiar combination and concurrence of favoring circumstances for the accomplishment of the purposes which are now well understood and can be explained, and a knowledge of which is essential to those who would comprehend the great Sepoy Rebellion. We will now state them, and, in doing this, will show how it was possible for such a rebellion to be then originated and carried out.

I. The first and most important fact was the position of the Emperor of Delhi—he in whose name and for whose interests it was inaugurated. We have already noticed the circumstances under which the alien power of the Mogul entered India, and at last came to rule from Calcutta to Cabul. With the sense of cruelty, injustice, and wrong that rankled in the hearts of the Hindoos against these foreigners, no length of time had ever reconciled them to their presence in their country. Thus, the last thing we could have imagined possible in 1857 was, that these two peoples could find a common ground of agreement on which they could stand together; and that expectation was the confidence of Englishmen in India. They leaned with confidence upon the Hindoos, whom they had elevated from the rule of Mohammedan injustice, believing that so long as they were content and satisfied the English empire was safe, no matter how the Mohammedans might rage. So they thought, and did not even dream that these ancient and inveterate foes were finding a ground of agreement, and were wide

awake, plotting the terrible arrangements that were so soon to burst in fire and bloodshed over the land.

In the East, where there are no constitutions or popular governments, personal influence in a sovereign is every thing; the despotic powers have only their individual adaptation and prestige to depend upon to commend their rule. It is a maxim with them, that “a king who has no eyes in his head is useless.” In reference to the poor, old, mutilated Emperor of Delhi, (grandfather of the one whose portrait is herein given,) it had much more than a metaphorical meaning. Its literal truth led to that state of general conviction of Mogul imbecility, and the necessity of having the paramount power of India in hands able to maintain its peace, and which would at the same time respect the rights of the falling dynasty, and all others concerned, which led soon after to the consummation of that Treaty between the Emperor and the English Government, in which his Imperial Majesty consented to surrender to them his authority and power (a poor show it then was) for certain considerations. That is, he agreed that the British were to assume the government of the country, and rule in his name, on condition that they would guarantee to himself and his successors forever the following compensations:

(1.) He was to be recognized as titular Emperor. His title was sounding enough to become a higher condition. How absurd it seems, when we quote its translation in full: “The Sun of the Faith, Lord of the World, Master of the Universe and of the Honorable East India Company, King of India and of the Infidels, the Superior of the Governor-General, and Proprietor of the Soil from Sea to Sea!” This is surely enough for any mortal, especially when it is connected with a safe salary nearly as large as itself!

(2.) He was still to be the fountain of honor, so that all the sunnuds (patents) of nobility, constituting Rajahs, Nawabs, etc., were to be made out in his name, and sealed with his signet.

(3.) An embassador of England was to reside at his Court, to be the official organ of communication between himself and the English Government.

(4.) He was to retain his royal residences, the one in Delhi being regularly fortified, and occupying probably one fourth of the area of the city. And,

(5.) His imperial revenue was to be made sure, and punctually paid from the British Treasury.

He was asked how much that revenue must be? He replied, “Thirteen and a half lakhs of rupees annually”—$675,000 per annum. And as matters go in the East, where kings are supposed to own the soil, and can levy their own jumma (tax) upon every cultivated acre of it, this was not considered an unreasonable or unusual demand.

The terms were accepted, and the British moved their authority west of the Kurrumnasa, assumed the civil, political, and military control of Hindustan proper, and the Mogul Emperor resigned the heavy cares of State and went to house-keeping on his $675,000 per year. He assuredly might think that he had made a good bargain for himself and his family with his commercial patrons, the East India Company, while the whole resources of Great Britain were pledged to every item of the engagement—and he certainly might have done tolerably well under the circumstances. But one thing stood in the way. He and his outraged the laws of Heaven; the result was a ruin which in its completeness has had hardly a parallel in the history of any earthly dynasty.

With idleness and fullness of bread came mischief and vileness for three generations, increasing in their terrible tendencies, as the sins of the fathers were shared by, and visited upon, their children, until hideous ruin engulphed the whole concern, and left not a wreck behind.

To the American reader it must seem amazing to state that the $675,000 per annum proved utterly insufficient to enable the last Emperor to live and keep out of debt; yet so it was. He really could not “make ends meet” from year to year on this splendid allowance, paid to the day, and paid in gold. But the explanation is at hand.

Had the duality of the marriage relation been recognized at the

Court of Delhi, it is very probable that it might have escaped the guilt and misery which hastened its destruction. Men in high or low station cannot violate the laws of God, even when their creed sanctions that violation, without incurring the penalty which is sure to come, sooner or later. Of this truth there never was a more marked example than was exhibited within these high and bastioned walls. The three generations during which this wrath was “treasuring up” its force but made it more overwhelming when its overthrow of desolation came. It was expressly stipulated in the treaty that the munificent provision made for the Emperor was to cover all claims. Out of the $675,000 per annum he was required to support the retinue of relations and dependents collected within the walls of the imperial residence. But fifty years of idleness, and the license of a sensual creed, which permitted unlimited polygamy, made that which would have been easy to virtue impossible to vice.

The Eden of God had but one Eve in it, and she reigned as queen in the pure affections of the happy and noble man for whom God had made her. Within the walls of that Delhi palace Shah Jehan could inscribe the words,

“If there be a paradise on the face of the earth,

It is this—it is this—it is this!”

For he loved one only, and was faithful to her, and has enshrined her memory while the world stands in the matchless Taj Mahal. Few, if any, of his race imitated his virtue in this regard; and least of all his last descendants. Fifteen years ago the Delhi “paradise” had become changed into a very pandemonium. Here were crowded together twelve hundred kings and queens—for all the descendants of the Emperors assumed the title of “Sulateens”—with ten times as many persons to wait upon them, so that the population of the palaces were actually estimated at twelve thousand persons. Glorying in their “royal blood,” they held themselves superior to all efforts to earn their living by honest labor, and fastened, like so many parasites, upon the old Emperor's yearly allowance. “But what was that among so many,” and they

so constantly on the increase? So here the “kings” and “queens” of the house of Timour were found lying about in scores, like broods of vermin, without sufficient food to eat, or decent clothing to wear, and literally eating up each other. Yet, notwithstanding, their insolence and pride were exactly equal to their poverty; so that one of these kings, who had not more than fifty shillings per month for his share wherewith to subsist himself and his family, in writing to the Representative of the British Government at the Court, would address him as “Fidwee Khass,” our particular slave; and would expect to be addressed in reply with, “Your Majesty's commands have been received by your slave!”

Living in royalty on twenty-five dollars per month, or less, each of these worthies, on choosing a wife, or adding another to those he had before, would feel it necessary, for his rank's sake, to settle upon her a dowry of five lakhs of rupees, (two hundred and fifty thousand dollars,) while actually the royal scamp did not own fifty dollars in the world. His only accomplishment or occupation was playing on the “Sitar,” and singing the King's verses, for this king was ambitious of a poet's title, and they flattered the old gentleman's whim. Did the world ever witness such a farce!

Perhaps at the time I first saw the palace of Delhi, with this state of things then in full operation, the eye of God did not look down upon a mass of humanity more dissatisfied, more vile, more proud, and more mean, than the crowd of hungry Shazadahs who pressed against each other for subsistence within the walls of that fortification. All being royal blood, of course they could not soil their hands to gain an honest living; every man and woman of them must be supported out of the imperial allowance.

It was a simple impossibility for the English Government to meet the necessities of this case, or satisfy the demands of this greedy, hungry, and rapidly increasing crew. Twice had the Emperor's appeal been yielded to, and the grant increased from thirteen and a half, to eighteen lakhs, so that in 1857 they were receiving $900,000 per annum; but the limit had been reached at last. The English would neither pay the debts which they

contracted nor increase the yearly allowance. The country would not endure it.

The humiliating ceremonies, so tenaciously required by the Emperor on receiving any member of the English Government, had become increasingly irksome and annoying as time rolled on and this condition of things developed, until it began to be felt that the Great Mogul pageant was a bore. Lord Amherst, a former Governor-General, at length refused to visit the Emperor if expected, according to Delhi court etiquette, to do so with bare feet, bowed head, and joined hands. He declared he would only visit him on terms of honorable equality, and not as an inferior. Both he and Lord Bentinck refused any longer to stand in “the Presence,” but demanded a State chair on the right hand of the Emperor, and to be received as an equal. This shocked the Emperor's feelings, but he had to give in. Then came the suspension of the “Nuzzer”—the yearly present—a symbol of allegiance or confession of suzerainty. The value was not withheld, but added to the yearly allowance; but the Emperor refused to accept it in this form.

In 1849, on the death of the heir apparent, Lord Dalhousie, then Governor-General, opened negotiations designed to abolish this pageant of the Great Mogul, and offered terms to the next heir to abdicate the throne, vacate the Delhi Palace, and sink their high titles, retiring to the Kootub Palace and a private position, so that the large family might be placed under proper restrictions and required to obtain education, and fit themselves for stations where they could earn their living. But the merciful and wise proposal was misapprehended by them: instead of appreciating it, it thoroughly alarmed them. They chose to consider that their very existence was attacked. They would rather continue to fester and starve together within those walls than to separate and rouse themselves to action and honest employment; so they began to talk louder than ever about their “wrongs,” and the “insults” offered them by the English Government, prominent among which was the refusal any longer to give to each of these princes, whenever

he chose to show his face in public, the royal salute of his “rank.” But the English had deliberately come to the conclusion that this was a foolish and ridiculous waste of the national powder, and ought to cease forever.

Thus the Court — Emperor Begums, Sultans and Sultanas, Shazadas, Eunuchs, and followers, all in a ferment of dissension and hatred of English rule—became a center to which all disaffected elements naturally tended.

These men became the life and soul of the great conspiracy for the overthrow of the English power and the expulsion of Christianity from India, and for the elevation once more of Mohammedan supremacy over the Hindoo nations. Yielding to their influence, and that of the Sepoys, as will be narrated in our next chapter, the old Emperor committed himself fully, without counting the cost, to the fearful struggle.

The reader can well understand what an “elephant” the English Government had here on its hands, and in what perplexity they were as to what they should do with it.

This “high-born” population thus pressed for the means of subsistence within these walls, instead of being required to shift for themselves and quietly sink among the crowd without. When the writer reached India, in 1856, this state of things was ripening to its natural consummation. The different members of the Emperor's great family circle were fast becoming rallying points for the dissatisfied and disaffected. Let loose upon the community, they were every-where disgusting people by their insolence and knavery, so that the English magistrates in Delhi had to stand between them and their victims. The prestige of their names was fast diminishing, and they were falling into utter insignificance and contempt. This was true even of the highest of them. It was these “idle hands” that Satan employed to do much of the “mischief” wrought during the fearful rebellion of 1857—an event which consummated their own ruin, and sent scores of them to the gallows.

In the “good old days” of their rule they had their own way of

relieving any financial pressure, as soon as it was felt, by “loans” which were never paid, or by exactions from which there was no appeal or escape. But in 1857 it was no longer possible to practice in this way. The palace people had to let other men's money alone, and were required to live within their means, and those who trusted them had now to do so on their own responsibility. The Government of England refused to pay a dollar of their debts or grant any further increase to their allowance. How they raged over this resolve! Exhortations to do something, or fit themselves for positions which would support them, were all thrown away upon them, or, worse, they held the advice to be an insult. They were royal, and could not think of work; so they raged against the Government that stood between them and those whom they used to victimize, and sighed for the days when they could have relieved their necessities at the expense of other men. It need not be wondered at that such people hated English rule, and resolved that, if ever the opportunity came within their reach, they would be revenged upon the race who compelled them to be honest.

Just in proportion to this impotent rage, of which the Government was well aware, most of the Hindoo princes around were exultant to think that the Great Mogul had found a master at last—that there was a strong hand on the bridle in his jaws, to hold him back from trampling on the rights of other people. The Shroffs (native Bankers) and moneyed men in the bazaars were in high glee, knowing that the rupees in their coffers were all safe under the protection of England's power, and that none could make them afraid.

To all this, if you add the religious hate, you have the entire case of the Delhi Court. How these men raged as they remembered that their Crescent had gone down before the hated Cross; that where they had ruled and tyrannized for seven hundred years Christianity was now triumphant. They detest England: they will always do so: not because of her nationality, but for her faith. They would hate Americans all the same if we were there. To

Christianity they are irreconcilably antagonistic. They detest the doctrine of a divine Christ, and his followers have to share his odium at their hands. Alas, it is simple truth to say, that if the Lord Jesus were to come down from heaven to-day, and put himself in their power, they would as assuredly crucify him afresh in the streets of Delhi for saying he was “the Son of God,” as did the Jews in Jerusalem eighteen hundred years ago. You have only to read their “Sacred Kulma” to be assured of this spirit, and understand their rage against him; while their fearful deeds in 1857-8 upon his followers were a commentary on the Kulma, written with Christian blood; a record over which they gloat, and in the extent of which they still glory. Sad and abundant evidence of this fact is to follow in these pages; yet all this hatred and determination would have been utterly powerless had it stood alone—had the Hindoos not so strangely and unexpectedly united themselves with it.

2. This leads us to the consideration of the peculiar fact which, for once, brought the Moslem and Hindoo elements of the country into union and a common interest.

Lord Lake, the English General, had defeated the Mahratta chief, Bajee Rao, whose title, the Peishwa, was derived from a Brahmin dynasty founded at Poonah by Belajee Wiswanath. This title formerly meant Prime Minister, but its holders rose from that position to sovereign authority by usurpation and opportunity, and, in view of the high-caste assumptions of the Mahratta nation, their sovereign seems to have laid claim to a sort of headship in Hindooism, and so “Peishwa” became a religious as well as a secular title, and carried a great influence with it in the estimation of the Hindoos.

Duff, the historian of the time, gives a fearful picture of the licentiousness which prevailed at Bajee Rao's capital in 1816, and of his perfidy in attempting the assassination, by treachery, of Mr. Elphinstone, the English Embassador, and in the death of several Europeans whom he caused to be killed in cold blood, as well as the families of the native troops in their service. His ferocious

and vindictive orders, issued on the 5th of November, 1817, foreshadowed too truly other orders of a similar nature issued in July, 1857, by him to whom he transferred his home and fortune. The adopted son was worthy of his putative father. That son was Nana Sahib. The name of the author of the Cawnpore massacre is, of course, well known.

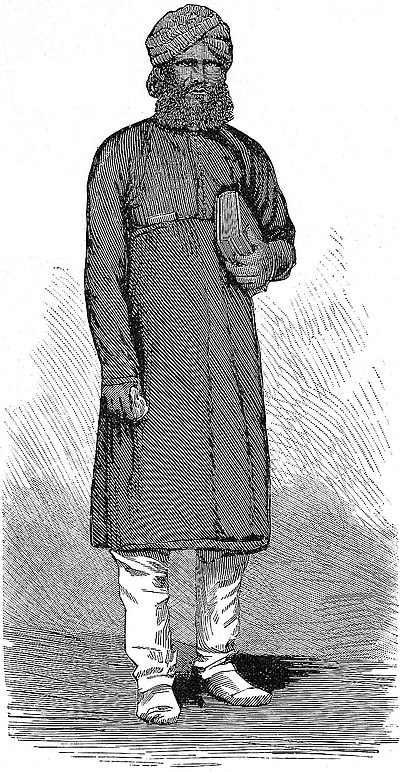

The picture of him here presented was drawn by Major O'Gandini, and sent home from India. He was fat, with that unhealthy corpulence which marks the Eastern voluptuary, of sallow complexion and middle height, with strongly marked features. He did not speak a word of English. His age at the time of the massacre was about thirty-six years. As this man will ever be identified with the sanguinary fame of Cawnpore, it seems appropriate to give the reader a more definite account of who he was, and his antecedents, as furnished by Trevelyan.

His full name was Seereek Dhoondoo Punth, but the execration of mankind has found his cluster of titles too long for use, and prefers the more familiar appellation of “The Nana Sahib.”

Bajee Rao, the Peishwa of Poonah, was the last monarch of the Mahrattas, who, for many years, kept Central India in war and confusion. The English Government being driven by his faithlessness and treachery to dethrone the old man, assigned him a residence at Bithoor, a few miles from Cawnpore, which he occupied until his death, in 1851. With his traditions, his annuity of eight lakhs of rupees ($400,000) yearly, and his host of retainers, Bajee Rao led a splendid life, so far as this world was concerned. But the old Mahratta had one sore trial: he had no son to inherit his possessions, perpetuate his name, and apply the torch to his funeral pyre. This last office, according to the Hindoo faith, can only be performed properly by a filial hand. In this strait he had recourse to adoption, a ceremony which, by Hindoo law, entitles the favored individual to all the rights and privileges of an heir born of the body. His choice fell upon this Seereek Dhoondoo Punth, who, according to some, was the son of a corn merchant of Poonah, while others maintain that he was the offspring of a poor Konkanee Brahmin,

and first saw the light at Venn, a miserable little village near Bombay. The Nana was educated for his position; and, on the death of his benefactor, he entered into possession of his princely home and his immense private fortune. But this did not satisfy the Nana. He demanded from the British Government, in addition, the title and the yearly pension which they had granted to his adoptive father. His claim was disallowed, as the pension was purely in the form of an annuity to the late King. But the Nana was not to be foiled. Failing with the Calcutta authorities, he transferred his appeal to London, and dispatched an agent to prosecute it there. This opens another amazing chapter in the history of this man. The person selected, and who had so much to do afterward with the massacre of the ladies and children, was his confidential man of business, Azeemoolah Khan, a clever adventurer, who began life as a kitmutgar—a waiter at table. He thus acquired a knowledge of the English tongue, to which he afterward added French, and came at length to speak and write both with much fluency. Leaving service to pursue his studies, he afterward became a school-teacher, and in this latter position attracted the notice of the Nana, who made him his Vakeel, or Prime Agent, and sent him to London to prosecute his claims. Azeemoolah arrived in town during the height of “the season” of 1854, and was welcomed into “society” with no inquiry as to antecedents. Passing himself off as an Indian prince, and being abundantly furnished with ways and means, and having, withal, a most presentable contour, he gained admission into the most distinguished circles, making a very decided sensation. He speedily became a lion, and obtained more than a lion's share of the sweetest of all flattery—the ladies voted him “charming.” Handsome and witty, endowed with plenty of assurance, and an apparent abundance of diamonds and Cashmere shawls, the ex-kitmutgar seemed as fine a gentleman as the Prime Minister of Nepaul or the Maharajah of the Punjab, both of whom had been lately in London.

In addition to the political business which he had in hand, Azeemoolah was at one time prosecuting a suit of his own of a more

delicate nature; but, happily for the fair Englishwoman who was the object of his attentions, her friends interfered and saved her from becoming an item in the harem of this Mohammedan polygamist. He returned to India by Constantinople, and visited the Crimea, where the war was then raging between England and Russia. He bore to his master the tidings of his unsuccessful efforts on his behalf, but consoled him with the assurance that the youthful vigor of the Russian power would soon overthrow the decaying strength of England, and then a decisive blow would be sufficient to destroy their yoke in the East. Subtle and bloodthirsty, Azeemoolah betrayed no animosity until the outburst of the Rebellion, and then he became the presiding genius of the assault and final massacre. Meanwhile he moved amid English society at Cawnpore with such deep dissimulation as to awaken no suspicion; and he was even the whole time carrying on correspondence with more than one noble lady in England, who had allowed herself, in her too confiding disposition, to be betrayed into a hasty admiration of this swarthy adventurer: so that, on the first day of Havelock's entrance, when he and his men came straight from “the Slaughter-House” and fatal Well, to the Palace of Bithoor, they discovered, among the possessions of this scoundrel, the letters of these titled ladies, couched in terms of the most courteous friendship. How little they suspected the true character of their correspondent! and how bitter and painful were the emotions which, under such circumstances, their letters raised in the breasts of Havelock's men! And yet this sleek and wary wretch was educated and courtly, even to fascination, while the heart beneath his gorgeous vest cherished the purposes of the tiger and the fiend. So much for education and refinement without religion or the fear of God.

Dr. Russell, “the Times' Correspondent,” mentions having met Azeemoolah in the Crimea, seeing with his own eyes how matters were going on there. He was fresh from England, where, a few weeks before, he might have been seen moving complacently in London drawing-rooms, or cantering on Brighton Downs, the

center of an admiring bevy of English damsels; but in the Crimea the secret of his soul was betrayed when, one evening, in a large party, he was incautious enough to remark that the Russians and the Turks should cease to quarrel, and join and take India. The remark caused some feeling, but aroused no suspicion of the lurking vengeance. India could gain nothing by such a change of masters. He knew this well enough; but such a change would humble England, and probably suspend or annihilate Christian missions there: and these results would be to him a full compensation for the change.

The sensual and superstitious Maharajah of Bithoor—as Nana Sahib was called—had thus found an agent after his own heart to work out his will. Bithoor Palace, where the Nana resided, was spacious, and richly furnished in European style. All the reception-rooms were decorated with immense mirrors, and massive chandeliers in variegated glass, and of the most recent manufacture; the floors were covered with the finest productions of the Indian looms, and all the appurtenances of Eastern splendor were strewed about in amazing profusion; but it would be impossible to lift the vail that must rest on the private life of this man. Nowhere was the mystery of iniquity deeper and darker than in this Palace of Bithoor. It was a nest worthy of such a vulture. There were apartments in that palace horribly unfit for any human eye, where both European and native artists had done their utmost to gratify the corrupt master, who was willing to incur any expense for the completion of his loathsome picture-gallery.

In the apartments open to the inspection of English visitors there was, of course, nothing that could shock either modesty or humanity, though a person of fastidious taste might take exception to the arrangement of the heterogeneous collection of furniture and decorations with which the Nana Sahib had filled his house when he aimed to blend the complicated domestic appliances of the European with the few and simple requirements of the Oriental.

The Maharajah had a large and excellent stable of horses, elephants, and camels; a well-appointed kennel; a menagerie of

pigeons, falcons, peacocks, and apes, which would have done credit to any Eastern monarch from the days of Solomon downward. His armory was stocked with weapons of every age and country; his reception-rooms sparkled with mirrors and chandeliers that had come direct from Birmingham; his equipages had stood within a twelvemonth in the warehouses of London. He possessed a vast store of gold and silver plate, and his wardrobe overflowed with Cashmere shawls and jewelry, which, when exhibited on gala days, were regarded with longing eyes by the English ladies of Cawnpore: for the Nana seldom missed an occasion for giving a ball or a banquet in European style to the society of the station, although he would never accept an entertainment in return, because the English Government, which refused to regard him as a royal personage, would not allow him the honor of a salute of twenty-one guns. On these occasions the Maharajah presented himself in his panoply of kincob and Cashmere, crowned with a tiara of pearls and diamonds—as here represented—the great ruby in the center, and girt with old Bajee Rao's sword of State, which report valued at three lakhs of rupees, ($150,000.) The Maharajah mixed freely with the company, inquired after the health of the Major's lady, congratulated the Judge on his rumored promotion to the Supreme Court, joked the Assistant Magistrate about his last mishap in the hunting-field, and complimented the belle of the evening on the color she had brought down from the hills of Simla.

All this was going on when the writer was in Cawnpore in the fall of 1856. These costly festivities were then provided for and enjoyed by the very persons—ladies, children, and gentlemen—who were, before ten months had passed, ruthlessly butchered in cold blood by their quondam host. Till his hour arrived nothing could exceed the cordiality which he managed to display in his intercourse with the English. The persons in authority placed implicit confidence in his friendship and good faith, and the young officers emphatically pronounced him “a capital fellow.” He had a nod, a kind word, for every Englishman in the station; hunting

parties and jewelry for the men, and picnics and Cashmere shawls for the ladies. If a subaltern's wife required change of air the Maharajah's carriage was at the service of the young couple, and the European apartments at Bithoor were put in order to receive them. If a civilian had overworked himself in court, he had but to speak the word, and the Maharajah's elephants were sent to the Oude jungles for him to go tiger hunting; but none the less did he ever, for a moment, forget the grudge he bore the English people. While his face was all smiles, in his heart of hearts he brooded over the judgment of the Government, and the refusal of his despised claim.

The men who, with his presented sapphires and rubies glittering on their fingers, sat there laughing around his table, had each and all been doomed to die by a warrant that admitted of no appeal. He had sworn that the injustice should be expiated by the blood of ladies who had never heard his grievance named, of babies who had been born years after the question of that grievance had passed into oblivion. The great crime of Cawnpore blackened the pages of history with a far deeper stain than Sicilian vespers or St. Bartholomew massacres, for this atrocious deed was prompted neither by diseased nor mistaken patriotism, nor by the madness of superstition. The motives of the deed were as mean as the execution was cowardly and treacherous. Among the subordinate villains there might be some who were possessed by bigotry and class hatred, but Nana Sahib was actuated by no higher impulses than ruffled pride and disappointed avarice.

The Hindoos, and particularly the military class of them, looked up to this man as their Peishwa. His position gave him immense influence. They would go with him to the side which he espoused. It is understood that he was tampered with, and made a tool of, by the Delhi faction under promise that when the English were expelled the country the Emperor would recognize his claims, and give him the throne of his reputed father at Poonah; so he threw in his lot with the conspiracy and bided his time.

3. The Mohammedan monopoly of place and power is another

consideration to be remembered in understanding the character and extent of this vast combination against Christian civilization.

This gave them their opportunity to organize their plans and work up the conspiracy. The Sepoy army, with the “Contingents” at native courts, native police, and, we may also add, the armed followers of the Rajahs and Nawabs who favored the rising, constituted an armed body of men fully five hundred thousand strong—the life and soul of the whole being the native “Bengal Array,” very largely Brahminical. Over these ignorant, superstitious, and fanatical forces, whether as military, commissariat, civil, legal, or financial subordinate officers, were these Mohammedan officials, so that a perfect organization, from Delhi throughout the whole land, was being formed, and it only now needed safe means of communication between the several parts, so that the central conspiracy could receive information or send its arrangements through men whom it could entirely trust, and who were its willing and ready agents. But this, too, was supplied, as we shall see.

The Sepoy army mounted guard upon the forts, the magazines, and the treasuries of India; and when their hour had come, and all was prepared, they held in their own hands the key of the coined millions of the public money, its vast stores of munitions of war, and its strong places. The total of European troops then in India was exactly 45,522, of all arms; but of these 21,156 were away in Madras and Bombay, leaving only 24,366 for the East, center, and Punjab, and more than two thirds of these were off on the Western frontiers and in Burmah, so that in the entire Valley of the Ganges there were but two half regiments, one with Sir H. Lawrence in Lucknow, and the other at Cawnpore.

4. India was then not only without railroads, but was even destitute of common roads, while the rivers were unbridged, and there was every natural difficulty in the way of an army of white men moving through the land, with the heavy impedimenta which they require in such a climate, and in which respect the native troops, being so much less encumbered, so much more at home in the heat, and so well acquainted with the country, had their enemy at

every disadvantage, and especially as they sprung the struggle upon them in the very midst of the hot season, when sun-stroke would be sure to lay low more than were prostrated by the bullet.

To show the importance of one aspect of this difficulty: In 1856 there was but one made road in North India—“the Grand Trunk,” so called, from Calcutta to the Punjab. General Anson, the English Commander-in-chief, on the first alarm on the 10th of May, commenced to collect his forces and march upon Delhi. The distance was under four hundred miles; but so wretched were the roads, and having to drag his artillery through rivers, it was the 8th of June when his army reached Delhi, and nine tenths of all the massacre and mischief were accomplished during those twenty-eight days. On the other side the river the conditions of travel were equally bad. The Soane River is crossed by this Grand Trunk Road. There was, in 1856, no way but to drag through its deep sands and widespread waters with bullocks—I have been four hours going from one side to the other; and the wise Government, that for one hundred years had neglected to build a bridge, had erected a dak Bungalow (Travelers' Rest House) on either bank, to meet the clear necessity that if you had breakfasted on one side you would need your dinner when you reached the other! What it was to take troops, artillery, and commissariat through such a country the reader can imagine.

It is a consolation to add, as a sign of that wonderful progress toward a better state of things on which India has since entered, that I had the satisfaction of crossing that same Soane River in 1864 in a few minutes on a first-class railroad bridge, and to-day General Anson could come from Umballa to Delhi in twenty-four hours.

5. The annexation of Oude—the home of the Sepoy—and where, while it was under native administration, the military classes that took service under the British Government had peculiar privileges that annexation would annul, leaving them equal before the law with the rest of the people: this, with the turbulent character of the Talookdars (or Barons) of Oude, who held themselves above

law, and defied their King to collect revenue from them, or exact their obedience, along with the thousands of persons who made a living by the Court, and their relation to its duties, intrigues, necessities, and vices, and whose occupation would be gone were the country annexed and British rule introduced—all these were aroused to a pitch of frenzy when the plot was actually consummated, and were ready to join in any enterprise, no matter how wild or desperate, that promised an overthrow of the new condition of things. And, finally,

6. To these elements of disturbance and eager watchfulness for a change, has to be added the great fact of the growing fear of the extension of the Christian religion, and the founding of new Missions in the land, with the consequent and widespread fear that their own faiths were in imminent danger of overthrow. Confounding every white man with the Government, and regarding him as most certainly in the service and pay of the English, they looked upon each Missionary as an emissary, backed up by the entire power and resources of the Administration, and to be correspondingly feared. This was the general view, (of course the more enlightened knew better,) and the interested parties took good care to intensify it to the utmost of their ability.

The very pains taken by the English officials to deny it, and present the Government doctrine of “Neutrality,” only made matters worse; for Hindoos and Mohammedans could not imagine a ruling power without a religion, or without zeal for diffusion of its own faith. The denial, therefore, was not believed; it only intensified the conviction of the people that these words were used to conceal the truth, and could only be used as a pretext to blind them for the present, till the English were fully prepared for the most determined action against their castes and their faiths. So that every movement was watched, and every act misinterpreted; and those in high places were distracted by prejudices which were too blind and fanatical to allow them to listen to reason.

My own appearance in Lucknow and Bareilly as a Missionary, and the pioneer of a band soon to follow, caused a great deal of

talk and excitement, and was pointed to as a part of the plan which the Government was maturing against their religions.

They could also refer to the steady encroachments of Christian law upon their cherished institutions. Suttee had been prohibited, female infanticide made penal, the right of a convert to inherit property vindicated, the remarriage of widows made lawful, self-immolation at Juggernaut interdicted, Thuggeeism suppressed, caste slighted—and they dreaded what might come next, ere they should be entrapped into an utter loss of caste, and forced to embrace the Christian faith.

Such was the peculiar combination of circumstances that in 1856 gave to the disaffected portion of the people of India the opportunity to concentrate their energies, under the most favorable conditions of success, to strike a blow that would at once overthrow Christianity and English rule forever, and restore, as they thought, native supremacy and the abrogated institutions of their respective faiths. They really imagined that if they could but wipe out the few thousand English in the land their work would be done, and that Great Britain either could not, or would not, replace them, especially in view of the resistance to a re-occupation which they could then present.

In addition to the elements of preparation which have been already presented, there was needed, for their safety and success in their terrible enterprise, that the conspirators should have a medium of communication between the various parts of the country and those who were working with them, as, also, an agency to win over the wavering and consolidate the whole power, so that it might be well in hand when the time for action should come.

The post-office was soon distrusted as a medium of communication; nor did it quite answer their purpose. They needed a living agency. This was essential, and one, too, whose constant movements would occasion no surprise; but just such emissaries as they required were ready at hand in the persons of the Fakirs, or wandering saints of Hindustan.

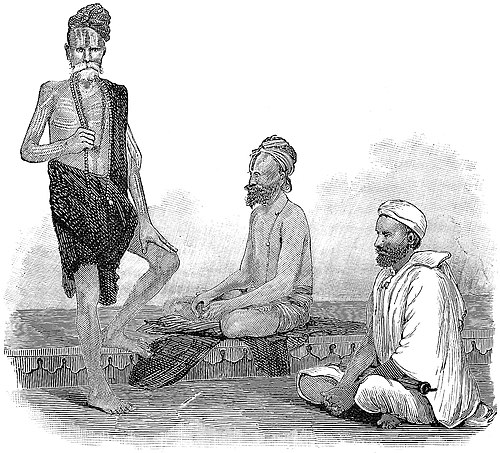

No account of India, or of the Sepoy Rebellion, would be

complete which did not include a proper description of these Fakirs. They are the saints of the Mohammedan and Hindoo systems. These horrible looking men, with their disheveled hair, naked bodies, and painted breasts and foreheads, are constantly roving over the country, visiting shrines, making pilgrimages, and performing religious services for their disciples. The Sepoys greatly honored and liberally patronized these spiritual guides. The post-office failing them, the chiefs of the conspiracy linked these Fakirs into the enterprise as the medium of communication; and they were so stationed that the orders transmitted, or the information desired, could be forwarded with a celerity and safety that was amazing.

It may be desired, for the sake of the information on this singular topic, to digress a little just here, before proceeding with the narrative. Of all the curses under which India and her daughters groan, it may safely be said that this profession of the Fakirs is one of the heaviest and most debasing. The world has not often beheld a truer illustration of putting “darkness for light” than is afforded in the character and influence of these ignorant, beastly-looking men—fellows that in any civilized land would be indicted as “common vagrants,” or hooted out of society as an intolerable outrage upon decency. But they swarm in India, infesting its highways, crowding its ghats and temples, creeping into its homes, and leading captive its poor, silly women. They hold the general mind of India in such craven fear that the courtly Rajah, riding in his silver howdah on the back of his elephant, and surrounded by his retinue, will often rise from his seat and salaam to one of these wretches as he goes by.

The Law-giver of India, while so jealously providing for the seclusion of the ladies of the land, expressly relaxes the rules in favor of four classes of men—Fakirs, Bards, Brahmins and their own servants—in the following section of the Code: “Mendicants, encomiasts, men prepared for a sacrifice, cooks, and other artisans are not prohibited from speaking to married women.”—Sec. 360. chap. viii. They can exercise their discretion how far they shall unvail themselves before them, though in their intercourse with Brahmins and Fakirs all restriction is usually laid aside. They are

as absolutely in their power as the female penitents of the Romish Church are in that of their priesthood, and even more so.

This state of things has lasted for long ages past. Alexander the Great, in his invasion of India, 326 B. C., found these very men as we see them there to-day. The historians of his expedition give us accurate descriptions of them. The Greeks were evidently amused and astonished at the sight of these ascetics, and, having no word in their language to describe them, they invented a new term, and called them Gymnosophists, (from gumnos, naked, and sophos, wise.) The patient endurance of pain and privation, the complete abstraction of some, the free quotations of the Shaster Slokes and maxims of their philosophy by the others, led the amazed Alexander and his troops to designate them as “Naked Philosophers,” more literally so than the pictures here presented, for, though in my possession, I did not dare to have those engraved whose nudity would have more fully justified the Greek designation; but they are still there, and of that class of the Fakirs a few words farther on will be in place.

The word “Fakir” (pronounced Fa-keer, with the a broad) is an Arabic term signifying “poor,” or a “poor man,” because they profess to have taken the vow of poverty, and, in theory, hold themselves above the necessity of home, property, or money, realizing their living as a religious right from the people wherever they come.

Some wander from place to place, some go on pilgrimages, and others locate themselves under a great banyan tree, or in the depths of a forest in some ruinous shrine or tomb, or on the bank of a river, and there receive the homage and offerings of their votaries.

I have often stood and looked at them in the wild jungle, miles away from a human habitation, filthy, naked, daubed with ashes and paint, and thought how like they seemed to those wretched creatures whom a merciful Saviour released from the power of evil spirits, and so compassionately restored to decency, to friends, and to their right minds.

Some few of these Fakirs are undoubtedly sincere in their profession of giving up the world, and its social and domestic relations, to embrace lives of solitude, mortification, or self-torture, or to devote themselves to a course of religious contemplation and asceticism; others of them do it from a motive of vain-glory, to be honored and worshiped by their deluded followers; while both of these classes expect, in addition, to accumulate thereby a stock of merit that will avail them in the next transmigration, and hasten their absorption into Brahm. But no one who has seen and known them can doubt that the great majority of the Fakirs are impostors and hypocrites.

A glance at the picture will enable the reader more fully to understand the descriptions which follow. These wear some clothing, but not much. The hair of the head is permitted to grow—in some cases not cut, and evidently not combed—from the time when they enter upon this profession. It grows at length longer than the body, when it is wound around the head in a rope-like coil, and is fastened with a wooden pin. The figure on the left hand of the picture in front is one of these. Having some doubts whether there was not some “make-believe” in the huge roll, I questioned a Fakir one day about it. Seizing the big pin, he pulled it out, and down fell the long line of hair trailing after him. It was, sure enough, all his own hair.

But even these are not the worst of the class. Quite a number of them give up wandering and locate, and engage in the most amazing manifestations of endurance and self-torture. A few must be mentioned. One will lash a pole to his body and fasten the arm to it, pointing upward, and endure the pain till that limb becomes rigid and cannot be taken down again. The pole is then removed. I saw one of them with both arms thus fixed, his hands some eighteen inches higher than his head, and utterly immovable. Some of them have been known to close the hand, and hold it so until the nails penetrated the flesh, and came out on the other side. Tavernier and others give engravings of some who have stood on one leg for years, and others who never lie down, supported only by a stick

or rope under their armpits, their legs meanwhile growing into hideous deformity, and breaking out in ulcers. Sticking a spear through the protruded tongue, or through the arm, is practiced, and so is hook-swinging—running sharp hooks through the small of the back deep enough to bear the man's weight—when he is raised twenty or thirty feet into the air and swung around. Some will lie for years on beds of iron spikes, like the one here represented, reading their Shaster and counting their beads; while their ranks furnish many of the voluntary victims who have immolated themselves beneath the wheels of Juggernaut. But there are tens of thousands of them who take to the profession simply because it gives them a living off the public, and who are mere wandering vagabonds.

A Self-torturing Fakir.

Many of them are animated by another class of motives. These hunger for fame—they have become Fakirs for the honor of the thing—are willing to suffer that they may be respected and adored by those who witness in wonder the amazing self-tortures which they will endure. An instance which may be worth relating will illustrate this aspect of the subject. It was turned into verse by a humorous Englishman when the case occurred, and we present it here. One of these self-glorifying Fakirs, after graduating to

saintship by long years of austerities and extensive pilgrimages, took it into his head that he could still further exalt his fame by riding about in a sort of Sedan chair with the seat stuck full of nails. Four men carried him from town to town, shaking him as little as possible. Great was the admiration of his endurance which awaited him every-where. At length (no doubt when his condition had become such that he was for the time disposed to listen to some friendly advice) a rich native gentleman, somewhat skeptical as to the value and need of this discipline, met him and tried very earnestly to persuade him to quit his uncomfortable seat, and have mercy upon himself. But here let Mr. Cambridge give the reasoning of the kind-hearted native, and point the moral of the story. He says to the Fakir:

“ ‘Can such wretches as you give to madness a vogue?

Though the priesthood of Fo on the vulgar impose

By squinting whole years at the end of their nose—

Though with cruel devices of mortification

They adore a vain idol of modern creation—

Does the God of the heavens such a service direct?

Can his Mercy approve a self-punishing sect?

Will his Wisdom be worshiped with chains and with nails,

Or e'er look for his rites in your noses and tails?

Come along to my house, and these penances leave,

Give your belly a feast, and your breech a reprieve.’

This reasoning unhinged each fanatical notion,

And staggered our saint in his chair of promotion.

At length, with reluctance, he rose from his seat,

And, resigning his nails and his fame for retreat,

Two weeks his new life he admired and enjoyed;

The third he with plenty and quiet was cloyed;

To live undistinguished to him was the pain.

An existence unnoticed he could not sustain.

In retirement he sighed for the fame-giving chair.

For the crowd to admire him, to reverence and stare:

No endearments of pleasure and ease could prevail.

He the saintship resumed, and new-larded his tail.”

The reference in the third line—to “squinting whole years at the end of his nose,” is a serious subject, and will be explained hereafter.

Sometimes Fakirs will undertake to perform a very painful and lengthened exercise in measuring the distance to the “sacred” city of Benares from some point, such as a shrine or famous temple,

even hundreds of miles away, though months or years may be required to complete the journey. I had once the opportunity of seeing one of these men performing this feat. When I met him he was on the Grand Trunk Road, over two hundred and forty miles from Benares. He had already accomplished about two hundred miles. A crowd accompanied him from village to village, as men turn out here to see Weston walk. He was a miserable-looking object, covered from the crown of his head to his feet with dust and mud. He would lay himself down flat on the road, his face in the dust, and with his finger would make a mark in front of his head on the ground; then he would rise and put his toes in that mark, and down he would go again, flat and at full length, make another line, rise, and put his toes in that, and so on, throughout the live-long day. When tired out he would make such a mark on the side of the road as he could safely find next morning, and then go back with the crowd to the last village which he had passed, where he would be fêted and honored, and next day would return to his mark and renew his weary way. I could not find out how much progress he usually made. It must have been very slow work—certainly less than one mile per day; and what weary months of hard toil lay between him and Benares is apparent. These wretches thus choose, and voluntarily lay upon themselves, penalties that no civilized government on earth would venture to inflict upon its most hardened criminals.

Some of these Yogees, in view of their supposed sanctity and superiority to all external considerations, hold themselves above obedience to law or the claims of common decency. I have myself seen one of them in the streets of Benares, in the middle of the day, when they were crowded with men and women—a man evidently over forty years of age—as naked as he was born, walking through the throng with the most complete shamelessness and unconcern! And if it were not for the terror of the English magistrate's order and whip, instead of one in a while, hundreds of these “naked philosophers” would scandalize those streets every day in the year, and “glory in their shame.”

There is a further aspect of this subject, and one so singular and serious that the reader will be as much surprised at the alleged divine law which requires it, as the sole and only path to moral purity and ultimate perfection, as he will be that men have ever been found who would undertake to conform themselves to the amazing and unique discipline by which it is to be attained. We may talk of self-denial and cross-bearing, but did the history of human endurance ever present any thing equal to the requirements of the following teachings?

In all the wide range of Hindoo Literature it is conceded that there is nothing so sublime, and even pure, as the disquisitions contained in the Bhagvat Geeta, (Bhagvat, Lord, Geeta, song—“the Song of the Lord.”) This book is an episode of the celebrated Mahabarata, and consists of conversations between the divine Kreeshna, (the incarnate God of the Hindoos, in his last avatar, or descent to earth in mortal form,) and his favorite pupil, the valiant Arjoona, commander-in-chief of the Pandoo forces.

Arjoona is religious as well as heroic, and in deep anxiety to know by what spiritual discipline he may reach perfection and permanent union with God. His Incarnate Deity undertakes to enlighten him in the following instructions.

To assist the reader in comprehending the teachings of this whimsical method of reaching “the higher life,” as practiced by the most sincere and yearning of India's religious devotees, I present a faithful picture of one of the class described, and who is at the same time one of the most celebrated of the Yogee order, just as I have seen him in Delhi, where the photograph was taken. The Yogee is the central figure. The Fakir standing is his attendant; the man to the right is one of the Yogee's devotees or worshipers, come to pay him the usual homage, expressed by his clasped hands. The Saint is silent, engaged in the meditation and abstraction, the rules of which we are going to present. His body is daubed with ashes till he looks as if covered with leprosy; the marks on his forehead are red, as they are on the face, and breast, and arms of his attendant. He holds no converse with mortal man, nor has he

done so for years. The Governor-General of India might pass by, but he would not condescend to look at him, nor deign a word of reply were he to speak to him. He is supposed to be dead to all things here below, and to have every sense and faculty absorbed in the contemplations enjoined in the following words of the Deity:

Kreeshna says to Arjoona: “The man who keepeth the outward accidents from entering his mind, and his eyes fixed in contemplation between his brows—who maketh the breath to pass through both his nostrils alike in expiration and inspiration—who is of subdued faculties, mind, and understanding, and hath set his heart upon salvation, and who is free from lust, fear, and anger—is forever blessed in this life; and being convinced that I am the cherisher of religious zeal, the lord of all worlds, and the friend of all nature, he shall obtain me and be blessed.

“The Yogee constantly exerciseth the spirit in private. He is recluse, of a subdued mind and spirit, free from hope, and free from perception. He planteth his own seat firmly on a spot that is undefiled, neither too high nor too low, and sitteth on the sacred grass which is called Koos, covered with a skin and a cloth. Here he whose business is the restraining of his passions should sit, with his mind fixed on one object alone, in the exercise of his devotion for the purification of his soul, keeping his head, his neck, and body steady without motion, his eyes fixed on the point of his nose, looking at no other place around. The peaceful soul released from fear, who would keep in the path of one who followed god, should restrain the mind, and, fixing it on me, depend on me alone. The Yogee of an humble mind, who thus constantly exerciseth his soul, obtaineth happiness incorporeal and supreme in me.”—Bhagvat Geeta, pp. 46-48.

It was one of these men, sitting thus naked, filthy, and supercilious, upon the steps of the Benares Ghat, receiving the homage and worship of the people, that drew from Bishop Thomson that strong remark which made such an impression upon those who heard him utter it.

The reader will bear in mind that Yog means the practice of

devotion in this special sense, and a Yogee is one devoted to God; and such a man as the one here presented is the highest style of saint that Hindoo theology or its Patanjala (School of Philosophy) can know. The demands of these tenets, and the amazing supremacy which their practice confers on such a devotee as this, are so extraordinary and beyond belief, that, instead of my own language, I prefer to state them in the words of Professor H. H. Wilson, the translator of the Veda. Describing the discipline of the Yogees, and the exaltations which they aim at, he says: “These practices consist chiefly of long-continued suppression of respiration; of inhaling and exhaling the breath in a particular manner; of sitting in eighty-four different attitudes; of fixing their eyes on the tips of their noses, and endeavoring by the force of mental abstraction to effect a union between the portion of vital spirit residing in the body and that which pervades all nature, and is identical with Shiva, considered as the supreme being, and source and essence of all creation. When this mystic union is effected, the Yogee is liberated in his living body from the clog of material encumbrance, and acquires an entire command over all worldly substance. He can make himself lighter than the lightest substances, heavier than the heaviest; can become as vast or as minute as he pleases; can traverse all space; can animate any dead body by transferring his spirit into it from his own frame; can render himself invisible; can attain all objects; become equally acquainted with the past, present, and future; and is finally united with Shiva, and consequently exempted from being born again upon earth. The superhuman faculties are acquired in various degrees, according to the greater or less perfection with which the initiatory processes have been performed.” All this is implicitly believed of them by their devotees, and they are honored accordingly with a boundless reverence.

The number of persons in the various orders of Yogees and Fakirs all over India must be immense. D'Herbelot, in his Bibliothèque Orientale, estimates them at 2,000,000, of which he thinks 800,000 are Mohammedan Fakirs. Ward's estimate seems to sustain this. But the influence of the British Government and its

laws, and the extension of education and missionary teaching, are steadily tending to the reduction of the number, by lowering the popular respect for the lazy crew that have so long consumed the industry of the struggling and superstitious people.

The expense of supporting them, at the lowest estimate—say two rupees per month for each Fakir—involves a drain of $12,000,000 per annum upon the industry of the country—a sum equal to what is contributed for the support of all the Christian clergy of the United States. Yet this is only one item of what their religion costs the Hindoos. Besides this come the claims of the regular priesthood, then of the Brahmins, then of the astrologers, encomiasts, etc., which this system creates—and Ward says they, with the Fakirs, make up in Bengal about one eighth of the population—millions of men year after year thus sponging upon their fellows, and engendering the ignorance, the superstition, the vice, the mendicity, the sycophancy, that necessitate a foreign rule in their magnificent land, as the only arrangement under which the majority could know peace, and be safe in possession of the few advantages which they enjoy. Truly heathenism—and above all Hindoo heathenism—is an expensive system of social and national life for any people. Error and vice don't pay. They are dearer far than truth and virtue under any circumstances.

Welcoming to their ranks, as they did, every vagabond of ability who had an aversion to labor, before the introduction of the British rule, these Fakirs, under pretenses of pilgrimages, used to wander, like the Gypsies of the West, over the country in bands of several thousands, but holding their character so sacred that the civil power dare not take cognizance of their conduct; so they would often lay entire neighborhoods under contribution, rob people of their wives, and commit any amount of enormities. In Dow's “Ferishta,” Vol. III, there is a singular account of a combination of them, twenty thousand strong, raising a rebellion against the Emperor Aurungzebe, selecting as their leader an old woman named Bistemia, who enjoyed a high fame for her spells and great skill in the magic art. The Emperor's general was something of

a wit. He gave out that he would resist her incantations by written spells, which he would put into the hands of his officers. His proved the more powerful, for a good reason: a battle, or rather a carnage, ensued, in which the old lady and her Fakir host were simply annihilated. Aurungzebe met his general, and, the historian tells us, had a good laugh with him over the success of his “spells.” Even as late as 1778 these militant saints thought themselves strong enough to measure swords with English troops, attacking Colonel Goddard in his march to Herapoor. But the Colonel, though much more merciful than the Mohammedan General, taught them by the sacrifice of a score or more of their number that they had better let carnal weapons alone. Though still saucy enough to the weak, they have ceased to act together in masses, or carry a worse weapon than a club in their peregrinations.

Usually each wandering Fakir has a religious relation to the high priest of some leading temple, and to him he surrenders some portion of the financial results of each tour at its termination. In view of this fact, they claim free quarters in all the temples which they pass. Their wide range of intercourse tends to make them well acquainted with public affairs—they hear all that is going on, and know the state of feeling and opinion, and communicate to their patron priests the information which they gather as they go.

This, then, was “the secret service” organized by the conspirators of the Sepoy Rebellion to convey their purposes and instructions—when they concluded that the post-office was no longer safe to them—and a very efficient and devoted “service” it proved to be for their objects.

One of Havelock's soldiers gave me a string of praying beads which he took from one of these Fakirs before they executed him. They intercepted him on his way to a Brigade of Sepoys, who had not yet risen, with a document concealed on his person from the Delhi leaders, directing the brigade to rise at once and kill their officers and the ladies and children of their station, and march immediately for Delhi to help the Emperor against the English. With this missive upon him, the Fakir—a stout, able fellow—was

passing Havelock's camp, when his movements attracted attention, and he was stopped. The interpreter was sent for, and the man interrogated. He gave a plausible account of himself—was a Holy Fakir, on his way to a certain shrine beyond, to perform his devotion—all the time twirling his beads in mental prayer, and so abstracted he could hardly condescend to reply to their inquiries. Some were for letting him go; others, who did not like his looks., thought it better to search him before doing so, when the terrible missive that was to plunge into a sudden and cruel death some forty English people, more than half of them ladies and children, was found upon him, and he was at once told to prepare for death. They gave him five minutes, and then dropped him by the roadside with the bullet. He held his beads to the last, and the soldier who took them from his hands gave them to me. But there were thousands of such agents at their command, and the loss of a few made little difference to the enterprise.

Out of the Presidency cities (Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay) there were then no hotels, and, save the Dak Bungalows (Travelers' Rest Houses) on the leading roads, a stranger was thrown entirely upon the hospitality of the civil and military officers of the English Government as he moved through the country. Freely and cordially was this hospitality extended to all comers, our kind hosts seeming to regard each visitant as conferring a favor rather than receiving it. On his departure they furnished him with a note of introduction to a friend in the next station, and there the same courtesy and attention were repeated.

Thrown thus so much and so constantly into the society of these gentlemen and their families, we were especially, as American strangers and missionaries, regarded with considerable interest, and our future success discussed from a variety of stand-points, according to the degree and character of the religious views and feelings of our kind entertainers. We had gone to India under the idea that it was a country whose tranquillity was fully assured, and whose peace could not be disturbed by any events likely to arise from any quarter. Our amazement may be imagined when we

discovered, as we so soon did, that there were apprehensions in the minds of many of these gentlemen of the existence of something unsafe, and even dangerous, around them; but as others of them treated the matter very lightly, and even ridiculed the idea of any necessity for anxiety, we, on our part, concluded that it was no particular business of ours, so we went on with our duty, leaving the future to be guided and controlled by the great Protector whom we were serving.

On reaching Lucknow, November 29, 1856, we found, rather to our surprise, that our note of introduction was to billet us in the “Residency,” (so famous for its siege and relief by General Havelock ten months later.) Lucknow was the splendid capital of the kingdom of Oude, whose sovereign, Wajid Ali Shah, had just been removed to Calcutta, and his dominions annexed by the British Government, on account of the long-continued misrule and oppression that had made Oude a neighborhood of misery and rapine to all the country around it. What the condition of its King and Court were is stated, without exaggeration, in a work issued from the American press about 1854, entitled “The Private Life of an Eastern King,” and also in Sleeman's “Recollections,” and other publications. Few sovereigns have ever been so utterly forgetful of the duties of a governor of men, or more thoroughly steeped in selfishness and sensuality, than was Wajid Ali Shah. His territories at length, from his misrule and neglect, became an unequaled scene of outrage and bloodshed, and a refuge for the dacoits (robbers) of Northern India, who would cross the Ganges at night and plunder in the British Territories all around, making good their retreat into Oude before daylight. Complaints were presented for years, and threats of annexation were served upon him, till they ceased to be heeded by the besotted and reckless man, whose cruelties and neglect of his people (in which, however, he only imitated each of his predecessors) led at last to his being removed from the throne he disgraced. He was transferred to Calcutta in the spring of 1856, and there, on a pension about equal to his royal revenues, he prosecutes his debaucheries without ruining a kingdom

any longer. The British Government annexed Oude to their territories, greatly to its relief and advantage. I present a picture of this royal sot, as he loved to display himself in all his jewels and finery.

During the week that we remained at Lucknow we were kindly entertained by a member of the new Government, (at the head of which was the celebrated Sir Henry Lawrence.) Every facility was afforded me in prosecuting my inquiries, and all information that I needed about the country, its condition and statistics, were freely communicated.

Lucknow then well deserved the character, so far as its external aspect was concerned, which Bayard Taylor gives it in his “India, China, and Japan,” when, standing on the iron bridge which spans the Goomtee, he exclaims, “All was lovely as the outer court of Paradise!” But, in what moral corruption were its five hundred thousand inhabitants seething! I had never before seen any thing approaching its aspect of depravity and armed violence. Every man carried a weapon—even the trader's sword lay beside his goods, ready to defend them against the lawless. I had not supposed there was a community of men in this world, such ferocious Ishmaelites, as I saw in that city. It was not safe for an unarmed man, black or white, to move among them. And, indeed, when I wanted to see the city thoroughly, it was considered essential to my safety that I should not go alone or unattended, so they kindly mounted me on the back of an elephant in a Government howdah, and gave me a Sepoy escort; and thus elevated, so that I could see every thing on the flat-roofed houses, and in the courts and streets below, I made my first acquaintance with the city of Lucknow, and saw heathenism and Mohammedanism in their unutterable vileness. I returned to the Residency in the evening sick at heart, and, for the moment, discouraged at the fearful task which we were undertaking, to save and Christianize such people.

Outside the city the whole country was a sort of camp. The Sepoy army was drawn chiefly from this military class of men. Indeed, the city of Lucknow was the capital of the Sepoy race.

The Talookdars (barons) of Oude (each in his own talook, setting up for himself, holding all he had, and taking all he was able to snatch from his neighbors) often defied their King, and refused to pay the jumma, (revenue,) and he could not obtain it unless by force of arms; and even here he was frequently defeated by their combining their forces against him. Mr. Mead has fully shown in his work—“The Sepoy Revolt”—how truly Oude had been for generations the paradise of adventurers, the Alsatia of India, the nursing-place and sanctuary of scoundrelism, almost beyond a parallel on earth. Sir William Sleeman's work on Oude is probably the most fearful record of aristocratic violence, perfidy, and blood, that has ever been compiled; yet it is written by one who opposed the annexation of the country to the British dominions, and who was regarded by the natives as their true friend. When I entered Oude there were known to be then standing two hundred and forty-six forts, with over eight thousand gunners to work the artillery on their walls, and connected with them were little armies, or bands of fighting men, to whom they were continually a place of shelter and defense. Annexation involved the razing of these forts, and the incorporation of a large amount of those blood-thirsty freebooters, and of the King's troops, into the Sepoy Army—for Lord Dalhousie, the Governor-General, did not know what else to do with them—but what elements of fierceness and lawlessness were thus added to the prejudice and fanaticism of the high caste Brahminical army can be well imagined. Thousands of these mercenaries who could not be employed, and who, with arms in their hands, were sent adrift to seek their fortunes, became the ready instruments of the Talookdars' tyranny and power, when His Excellency announced to them his intention of introducing the British system of land revenue into their country, for they well knew that these public improvements could be established only at the cost of their personal prerogatives and opportunities. The result is before the world.

Yet it was in such a country and among such a people, after months of careful inquiry and inspection of unoccupied fields, that

I concluded the Mission of the Methodist Episcopal Church should be established. We, with our gospel of peace and purity, had evidently found “those who needed us most;” and I had faith to believe that this warlike race, with all their force of character, could be redeemed, and would yet become good soldiers of Jesus Christ. Long after the hand which traces these lines shall have crumbled into the dust will the wide range of that beautiful valley, dotted with Christian churches, and cultivated by Christian hands, be bearing the rich fruition of these hopes.

Satisfied of the suitability of Lucknow to become the headquarters of our new Mission, I sought from a member of the Government (not Sir Henry Lawrence, however) some statistics of the kingdom, to be incorporated in my Report to the Board at New York. I shall long remember his surprise when he found that we seriously contemplated planting the standard of the cross there. He asked me to look at the people, to consider their inveterate prejudices, and the venerable character of their systems, and say if I thought any thing could ever be done there? So far was he from so believing that he considered it was madness for us to try, nor would our life be safe in attempting it. His mind was so made up on that question that he could lend no countenance to such an effort: in fact, he was no friend to Christian missions, and he intimated pretty plainly that he considered I would manifest more good sense were I retrace my steps to Calcutta, and take the first ship that left for America! I received no better encouragement when I afterward called on Sir James Outram—a good man, and one of the bravest generals that ever commanded an army. He could lead the advance that so gallantly captured that city; but to stand up for Jesus alone and unprotected, exposed to the rage of the Mohammedan and the Hindoo in their bazaars, seemed to the military hero something that ought not to be attempted in such a country as Oude. He shrugged his shoulders when I reminded him that, as to our safety, Christ our Master, whose commission we obeyed, would look to that; while our success was in the hands of the Holy Spirit, and duty alone was ours. But he could not see it, and

we parted never to meet again. The gallant man, so justly designated “The Bayard of India,” sleeps to-day in Westminster Abbey, among the illustrious dead whom England delights to honor.

Satisfied that we should end our wanderings, and regard Oude and Rohilcund as our mission-field, we sought for a house in Lucknow, but none could be found—all spare accommodation of the kind had been engaged by the officers connected with the increased civil and military establishments of the Government. So we were necessitated, as the next best thing, to go on to Bareilly, where a residence could be obtained, and wait for the future to open our way into Lucknow. We thus escaped the honor and risk of being numbered with those whom the relieving General, speaking for a sympathizing world, was pleased to designate “the more than illustrious garrison of Lucknow,” who for one hundred and forty-two days were shut up and besieged within the walls of the Residency and the adjacent buildings, and whose story we shall illustrate in its place.

With many of the survivors, male and female, I was intimately acquainted for years afterward, while my home subsequently was within fifteen minutes' walk of the ruins of the Residency itself

After full examination and inquiry, I had chosen this Kingdom of Oude and Province of Rohilcund (with the hill territory of Kumaon subsequently added) as our parish in India. In a full report to the Board in New York our reasons for the preference were fully given, and the fact was noted in the correspondence that the field chosen was one of those commended to my attention, before leaving America, by the Rev. Dr. Durbin, as one that might probably, on examination, be found pre-eminently suitable. His opinion and sagacity have been fully justified by the unqualified satisfaction of all concerned with the choice thus made. Our field, then, is the Valley of the Ganges, with the adjacent hill range bounded by the river Ganges on the west and south, and the great Himalaya Mountains on the north—a tract of India nearly as large as England without Scotland, being nearly four hundred and fifty miles long, and an average breadth of say one hundred and twenty

miles, containing more than eighteen millions of people, who are thus left in our hands by the well-understood courtesy of the other Missionary Societies in Europe and America, who respect our occupation, and consider us pledged to bring the means of grace and salvation within the reach of these dying millions. (The reader's attention is asked to the Map which is at the beginning of the volume for the localities intimated within or near the scenes of the Ramayana and Mahabarata, and its central position, in the very “throne land of Rama,” amid the most important of India's “holy shrines,” and where our Christianity can tell so powerfully upon the entire country.)

On my way to Bareilly I called to see the Missionaries of the American Presbyterian Church at Allahabad; and, after explaining my plans and our proposed field, I stated to them how much I felt the need of some native young man who knew a little English—one whom I could fully trust, and by whose aid I might do something while awaiting the arrival of the brethren to be sent to me from America. They had one such whom they thought, under the circumstances, they might spare for such a purpose, though he was very dear to them. His name was Joel. They kindly introduced me to him, and at once my heart went out toward him as just the person I needed. I introduce him here to my readers—my faithful helper, destined to become the first native minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church in India.

Joel had been taken when an orphan boy by the missionaries, and by them was educated and trained. He was at this time about twenty-two years of age, married to Emma, a lovely, gentle girl, four years younger than her husband. They had one little babe, and lived with Emma's widowed mother, a good Christian woman called “Peggy,” who doted upon her daughter, all the more, I suppose, because she was so fair and delicate. I remember them distinctly, because they were the first Christianized Hindoo household beneath whose roof I had yet sat down, and they seemed such a happy family. Joel had then gained so much of the English language that, by speaking slowly and using simple words, I could