The Zoologist/4th series, vol 4 (1900)/Issue 710/A Short History of the Bearded Titmouse, Gurney 1900

![]()

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse

- Parus biarmicus, Linn. S.N.

P. russicus, Gmelin.

Panurus biarmicus, Koch, Syst. d. Baier. Zool. p. 202.

Ægythalus biarmicus, Boie.

Mystacinus arundinaceus, Brehm.

M. dentatus, Brehm.

Calamophilus barbatus, K. and B.

Hypenites barbatus, Gloger.

Paroides biarmicus, Gray.

It is now generally admitted that there is only a single species of Bearded Titmouse, and that species stands by itself as a very well-marked genus (Panurus of Koch), with no nearer allies, in the opinion of a high authority, than Paradoxornis flavirostris of Bengal, and Cholornis paradoxa of China. Formerly better known as Calamophilus biarmicus, this curious bird is now nearly universally received by authors as Panurus biarmicus, but its position was for many years a moot point in ornithology, as the seven generic names at the head of my paper sufficiently indicate. Perhaps no one has done more to settle it finally than Professor Newton, who, in 1873, summed up the opinions of previous writers with his usual conciseness, and gave an excellent general account of the bird.

The "Reed Pheasant" of our Norfolk fenmen (so called from its resemblance in miniature to the nobler "longtails" of the battue) or "Maish [Marsh] Pheasant" as they sometimes dub it, or "Maish Tit" with a stress on the i—the Het Baardmannetje of the Dutch—has been regarded as a very remarkable bird, and has been the recipient of several English names.

For manifold reasons this species has long attracted the attention of naturalists, and the following notes and recollections of the bird in its haunts—which are in part drawn from an article in the Norfolk and Norwich Nat. Soc. Tr. (vi. p. 429)—are compiled from different sources.

It was discovered by the ever-enquiring author of the earliest treatise on Norfolk Birds, Sir Thomas Browne, who communicated his discovery to John Ray, who published the first notice and description in 1674, in a scarce little book of which Canon Tristram is fortunate in having a copy. All subsequent authors appear to have been ignorant of this publication of Ray's, and ignored it, and no continental naturalist describes the bird before Linnæus.

Certainly it seems as if Sir Thomas Browne could not have been cognisant of the Bearded Titmouse when he drew up his memorable List of Birds (about the year 1663), yet the bird must have been an inhabitant close to Norwich.

The picture of the Bearded Tit which Browne sent to Ray—probably delineated by the same hand which portrayed him the Manx Shearwater,[1]—a literary curiosity, if it existed still—is tersely described in Ray's 'A Collection of English Words not generally used,' as "A little Bird of a tawney colour on the back, and a blew head, yellow bill, black legs, shot in an Osiar [doubtless on the Yare] yard, called by Sr Tho. for distinction sake silerella," A concise description of an adult male.

In the 'Synopsis methodica avium,' by Ray, but published eight years after his death, the Bearded Tit finds a place (page 81) among birds doubtfully identified by Aldrovandus and others, as: "II. Salicaria, Gesn. An Silerella D. Brown? Avicula est minima; colore partim fusco, ut parte prona"; &c.

Distribution.

At the present day the Bearded Titmouse is limited to the Norfolk Broad[2] district, an area twenty-five by thirteen miles, of which part is marsh. Here it still breeds annually, and is found in little flocks throughout the autumn and winter, but whether all these flocks are the same individuals which summer on the broads may be doubted.

In some, if not in all, of its Dutch and German habitats it is alleged to be migratory. This is the character which Schlegel and Naumann give it, and one might expect the same in England. In Normandy it is only a summer visitant, but, on the other hand, in Luxemburg it is regarded as a winter visitant, and Keulemans has known it to occur in Holland in winter.

In Belgium it appears from Dubois's 'Oiseaux observés en Belgique' (1885) to be now very rare, though still to be sometimes seen in the marshes of Flanders and Antwerp, no doubt the same causes operating to reduce its numbers as in England. As it does not go further south than the Mediterranean, or further north than Pomerania, its migrations cannot be very great, as they are confined between 37° N. lat. and 56° N. lat. Norfolk is very near its northern and its western limits. But in an easterly direction its range is very extensive, for it appears to reach right across Asia—where it becomes slightly paler—into China.

According to l'Abbé David it is "extrèmement commune dans la region marécageuse qui's'étend au sud du coude septentrional du Hoangho" (the Yellow River), and this is on the authority of Col. Prjevalsky, who brought back large collections of insects and birds from that country. ('Orn. Miscellany,' ii. p. 191.)

It is also found in Turkestan ('Stray Feathers,' 1876, p. 154), where, according to Dr. Scully, it is exceedingly common. (Cf. map, p. 374.)

Increasing Scarceness.

We find very little about the Bearded Tit in the early authors, but this is not singular, because of the aquatic situations in which it resides, and Latham (1783) remarks that these birds had only been observed in marshy situations, as though, their peculiar characteristics not being known, there were some who thought they might be looked for in woods and thickets!

From Sir T. Browne's day (1674) to Sir William Hooker's (Diary 1807–40) there appears to be no Norfolk mention of the Bearded Tit. Hooker, occupied with plants, merely says that it was by no means infrequent at Surlingham Broad, which was for long after a favourite locality, and where a marshman named Trent (now dead) used, I am sorry to say, to shoot a great many. Then there is John Hunt, the Norwich birdstuffer, who remarks that in 1819 there were large flocks at Burlingham (? Surlingham), Norf. and Nor. Nat. Tr. (iii. p. 260); but ten years later we find the same Hunt speaking of it as not common (Stacy, Hist, of Norf.), which the brothers Paget, writing in 1834, qualify into "common in some seasons."

Contemporary with Hunt's second statement is a very descriptive letter from J.D. Hoy to the well-known naturalist Selby, printed in the Norf. and Nor. Nat. Trans, (ii. p. 402), and which was the basis of a lengthy communication to the Magazine of Nat. Hist. 1830, p. 328. Hoy writes to Selby as follows:—

"June 23rd, 1828.—Sir, having been highly gratified in looking over your splendid 'Illustrations of British Ornithology,' and thinking that anything you had not perhaps observed in the habits of some of our birds might not be uninteresting to you, I have ventured to forward you a few observations.....

"I have had several nests of that most beautiful and elegant of our indigenous birds, the Bearded Titmouse. The margins of the extensive pieces of water, called broads, in the south-eastern part of Norfolk, which are skirted with large tracts of reeds, are the favourite abode of this species: its nest is composed, on the outside, with the decayed leaves of the sedge and reed, intermixed with a few pieces of grass, and invariably lined with the top of the reeds in the same manner as the Reed Wren. It is not so compact a nest as the Reed Wren's; the eggs vary in number from four to six, pure white sprinkled all over with small purplish spots, rather confluent at the larger end; full size of the Greater Titmouse. The nest is generally placed in a tuft of grass or rushes near the ground by the side of the water ditches in the fens, sometimes on the broken-down reeds, but never suspended between the reed stems in the manner of the Reed Wren. In the autumn they disperse themselves in little parties along shore, wherever there is an acre or two of reeds; during the winter months they feed entirely on the seed of the reed, and so busily employed are they in searching for their food that I have taken them with a fine bird-lime twig attached to the end of a fishing-rod. When alarmed by any noise they drop down among the reeds, but soon resume their station again, climbing up the reed-stems with the greatest facility."

Though now slightly recovering its numbers, the Bearded Tit has become very scarce in Norfolk, and almost extinct in Suffolk. Self-interested marshmen and egg-collectors would like strangers to believe that this scarcity is owing to hard winters; but their own cupidity is one cause of the decrease, for the truth is, that Bearded Tits are not nearly so delicate as their frail appearance would seem to imply; indeed, Mr. E.T. Booth used to call them remarkably hardy, and in his 'Catalogue' says that they seem able to contend against severe weather with greater success than many much larger and apparently stronger birds. This I quite believe to be the case, for they are not tender in confinement.

Having asked the Rev. M.C. Bird, who lives among the broads, to keep notes as to their presence or absence, he being constantly on the spot, I received the following memoranda last spring:—

March 14th, 1899.—Four pairs seen.

April 14th.—A nest at Potter Heigham.

April 17th.—Three nests, with four, four, and five eggs respectively; two more nests, and a sixth taken.

April 25th.—Three nests found.

April 28th.—Additional nest with young a few days old.

May 1st.—Another nest.

May 6th.—The nest found on the 1st has eight eggs; another nest found to-day.

May 19th.—A nest with young flown.

With Mr. Bird's assistance I have compiled an estimate of the number of nests hatched off in 1898 on every broad in Norfolk where there is reason to think that there are any. This only gives a total for them all of thirty-three nests, as tabulated in the Trans. Norf. and Nor. Nat. Soc. (vi. p. 430), but the number may be slightly more. It is unnecessary to recapitulate the list, which has only a local interest, but we may assess the number of adult Bearded Tits in April, 1899, on Norfolk Broads, as certainly one hundred; but there were not more than seven nests on any one broad, and it will be a diminishing quantity unless the arm of the law is upheld. Happily there is a desire on all hands to do this, and one gentleman even negotiated for the purchase of an estate, it was said, for the sole purpose of protecting the Bearded Tits.

The following is an approximate estimate of their decrease in Norfolk in six decennial periods since 1838, but the earlier figures given are little more than a guess:—

| 1838 | 1848 | 1858 | 1868 | 1878 | 1888 | 1898 | |

| Number of Nests | 200 | 170 | 140 | 125 | 90 | 45 | 33 |

The number of broads on which they now nest is about eleven large, and ten small ones, not including Wroxham Broad, where boating has banished them, though the Grebes remain.

One cause of their decrease is that the celebrated broads are gradually, but it is to be feared surely, growing up, though there is another more potent reason. For years, prior to 1895, there was a systematic trade in their eggs, and every egg dealer and moth hunter helped himself. Such devastation was criminal, but happily it is stopped now.

Both birds and eggs are protected by law, and the remnant are already feeling benefit from the protection afforded by this salutary measure, which came into force on May 1st, 1895. The broads where the Bearded Tits have had the best chance of escaping persecution are the small private ones, and those places where the proprietors have allowed the reeds to grow instead of cutting them, thereby providing high cover, which is an asylum where many a nest may escape the keenest eye. Unfortunately for the birds, it is rather an easy nest to find, for a pair will choose one particular bed of reeds year after year rather than move away.

Since the drainage of Salthouse sea-broad in 1851, the Bearded Tit has ceased to breed there, but the reed beds in Cley, adjoining, are still large enough to attract occasional migrants. It is very likely that the examples met with by Dr. Power and others in 1895, and on several previous occasions near Cley sluice, and at Morston and Burnham further west, had crossed the German Ocean, as also those seen in a pond at Holt in September, 1898, and May, 1899. In December, 1899, four were seen at Wiveton, still further north, where they remained a month.

Habits.

In its nest, and all that concerns the Bearded Titmouse, a protective colour may readily be traced. The old cock's black moustaches (which in Mongolian specimens are narrower) are like the dark chinks in the reeds, while his tawny colouring harmonises with the brown tints of autumn, and in spring there is a bloom on his freshly moulted plumage which goes well with the bursting into leaf of all around. Nowhere is the blend of nature's harmony better seen than in the flowers, insects, and birds of the broads, where everything suits its surroundings.

It has been said that these moustaches, from which the bird takes its name, are movable, and that their play gives a peculiar animation to the bird's expression, and it is likely enough that during courtship and before the breeding season this is so. They are composed of a considerable number of feathers, and, though wanting in the hen, there is a perceptible lengthening in her corresponding feathers, which are white.

A more beautiful object than a cock Bearded Tit in April, clinging tail uppermost to a tall reed stem gently waved by each gust of wind, it is difficult to imagine. Except in the vicinity of their nests, or when curiosity gets the better of them, they are shy and inclined to hide, but by their nests they give every opportunity for inspection as they flit across one mown space after another, betraying by their very anxiety the eggs which they wish to conceal.

They become still more unsuspecting when they have young, care for which causes many a bird to defy danger; yet they have much of that strange sense which we call instinct, and which tells them to creep to their well-hidden domicile, rather than fly to it in the presence of the enemy.

If there is any wind, they are not likely to show themselves, and this has been noticed in South Russia, for a wind which is enough to wave the tops of the reeds is enough to keep the Tits at the bottom. But when all is quiet they venture to the reed-tops, and, when concealed for a shot at Wild Duck, one has in this way sometimes the delight of being surrounded by an inquisitive little flock, and this is the time to study their engaging and active ways.

The flight of the Bearded Tit may be described as laboured, as it flits rather than flies along with head rather high, in little parties just topping the reeds, and each bird half spreading the twelve graduated feathers of its heavy tail, intended to steer by, but surely incommoding rapid progress.

I have been surprised to find, when walking with an old marshman, an experienced "egger," how often he heard their notes when neither of us could see the bird, long experience in listening for the rarer, and to him profitable species, having sharpened his ear. The clear ringing of their call-notes, which one admirer compares to cymbals, and another to the mandoline, can never, says Lord Lilford, be mistaken for any other European bird by a good ear which has once heard it. By one observer the silvery notes are syllabled as "thein, thein," by another as "ping, ping," or, when alarmed, "churr, churr"; while the provincial name in the south of France is "Trintrin" (Crespon and Jaubert); but here its place is to some extent taken by Ægithalus pendulinus.

It is said that young Bearded Tits, after they have left the nest, sometimes nestle together in a cluster on the reeds of our broads, but this habit does not seem to have been observed on the Continent. Hoy's account of their habits has been quoted already, and need not be repeated (cf. letter, p. 361).

Their food is not entirely the seeds of the reed, but minute water insects and their larvæ, and one sent by me to the late Mr. Cordeaux contained a good deal of river sand. The reedcutters have told me of seeing them searching the floating "muds" of nearly severed reed, which I have no doubt is explained by the following note:—Mr. W.H. Dikes, having examined three specimens, writes that the crops did not contain a single seed, but, on the contrary, were completely filled with the Succinea amphibia in a perfect state, the shell being unbroken. These shells were closely packed together, the crop of one which was not larger than a hazel-nut containing twenty, and four of Pupa muscorum. (Mag. N.H. iii. p. 239.)

Nidification.

The Bearded Tit is a very early breeder. Booth says: "I have on several occasions seen young birds able to leave the nest by the 4th or 5th of May, and so late as the middle of August have known the female sitting on eggs" ('Rough Notes,' vol. i. p. 83). On one occasion I found some young as big as their parents in the middle of June, and on the same day an incomplete clutch of fresh eggs, which would indicate that they sometimes breed three times in a season, the first clutch of eggs being therefore hatched in April. Besides this, the number of eggs laid by Mr. Young's tame birds, to be mentioned presently, confirms me in thinking that they breed three, possibly even four times, in a very favourable season.

After the breeding season the young form themselves into family parties, but it is certainly not the case that the males and females keep distinct (cf. Mag. N.H., 1829, p. 224), and such a flock as fifty together ('Birds of Norfolk,' i. p. 151) is not to be heard of now in England.

Continental authors give all sorts of sites for the nest, such as a hut built for duck shooting, but in Norfolk it is placed among reeds (never in nettles, very exceptionally in rushy grass), and is said to take eight days in construction. It is generally a foot above the ground, if a swamp can be called ground, and never, to the best of my belief, suspended. The tallest and stoutest reeds in the reed-bed are its customary support, reeds eight feet high, sometimes quite sere, while exceptionally a nest is hid in a dwarf Alder or cluster of Sweet Gale (Bog Myrtle), a shrub with that aromatic odour which prevails on a dry marsh in June, the Cuckoo's favourite perch. Here it may be remarked that, common as the Cuckoo is round most of our broads, there is no record of its egg being deposited in the nest of the Bearded Tit, which is very singular.

The nests "are extremely liable to be submerged if the tides rise suddenly, either from a heavy fall of rain or a flow of salt water up the river. In such cases the birds at once commence a second nest on the top of their first edifice" (Booth, l.c.), I have not personally heard of any nests being submerged, but Booth was always an accurate observer, and can be trusted.

The nest is about 2·8 inches inside diameter, and is usually composed of the brown blades of the common Arundo, and lined with their feathery tops. A typical nest with its surroundings is reproduced in the Norf. and Nor. Nat. Tr. (vi. p. 434), from a photograph by Mr. R.B. Lodge, who writes:—"Within fifty yards of our boat we had two nests with eggs, six each, one with young birds, and one from which young had apparently flown, and I saw the young birds early in May flying about. At one nest at which I spent half a day squatting in the same sedge bush, the cock did most of the sitting; he was easily distinguished, even at a distance, as he had no tail.

They are the most fascinating birds I know, and the easiest to approach at the nest, especially when the young are hatched. All our nests were in sedge."

Other photographers have visited our broads and been successful, notably Mr. Oswin Lee ('Photographs of Brit. Birds,' pt. viii.), whose large plate is worthy of all commendation, while that by Mr. Kearton, in 'Our Rarer British-breeding Birds,' shows the eggs well in a characteristic bed of rushes. But the cleverest of all are the pictures taken by Mr. O.G. Pike (see pt. iv. of his recently published 'In Bird Land'), which, owing to his kindness, I am able to reproduce. It will be seen that in one the hen is feeding her young ones, which Mr. Pike observed that she did about every five minutes, distributing a beakful of green caterpillars equally among all. In the other plate Mr. Pike has caught the hen in the act of cleaning out the nest, which she did on about every fourth visit.

The eggs are very peculiar, and at the same time very pretty; white, with specks and wavy lines of brown, with a pink tinge when fresh, and a zone when incubated. They (the first clutch) are deposited in April, or even at the end of March possibly, and generally six in number, occasionally seven. Old Joshua, the companion of my rambles, averred that he had found two nests on the top of one another, and on another occasion twelve eggs in one nest, while a nest sent from Hickling to Mr. Frank Norgate contained ten eggs, but two of them were buried in the lining, and this year one was found at Hickling with eight eggs.

Joshua had also known them to sometimes lay the first egg before the nest was finished, and then, after a layer of material, more eggs, a common habit with true Titmice (Paridæ). An egg taken by Joshua was placed in an incubator by Mr. Evans, of Edinburgh, to ascertain the duration of its incubation, a subject he has specially studied, but the experiment was not successful. John Smith, of Yarmouth, considered the period to be thirteen days (Zool., 1846, p. 1497), and Tidemann fourteen. None of the small birds appear to exceed a fortnight, but in such a distinct form as Panurus there might be a difference of a day or two.

I can testify to its being a fact that the cock bird occasionally takes part in incubation, though this has been doubted by Keulemans, who had in confinement the beautiful examples figured in Dresser's 'Birds of Europe,' and probably ascertained from them that the duration of the moult was nearly five weeks. His excellent account of its habits as a cage bird and in a wild state in Holland is given in the 'Birds of Europe,' and again in Keuleman's 'Cage Birds,' an uncompleted work, and therefore but little known.

Description.

The adult male and female are almost too well known to need description. The prevailing colour is tawny orange, and in the cock the head is blue grey, with a black moustache on each cheek, long and pointed, with no apparent utility other than ornament. These beautiful colours are at their best from December to April 1st, after which they deteriorate. Females are never so handsome as males, and always lack the grey head, which is so beautiful: excellent descriptions are given in the 'Birds of Europe' from specimens which I supplied of both sexes. But the plumage of immaturity is far more remarkable.

For a long time after quitting the nest the young have black backs, and are cream-coloured, so that if Bonaparte gave his name of P. sibiricus to a young bird it was a very excusable mistake. Radde was nearly led into the same error ('Ibis,' 1889, p. 87).

It is said that young males can be distinguished by their more lemon-coloured bills. The nestling when only a day old has a brighter mouth than any other nestling bird in England, for the palate is red, with four little rows of black and white dots. Mr. Lodge tried to photograph a brood with their mouths open, but it was a failure, and my sketch is not sufficiently accurate for reproduction, indeed, it would be exceedingly difficult to give the vivid colours properly. The colour of young birds' mouths has not been sufficiently taken notice of. The nestling Blackcap's mouth is lake red, the nestling Willow Warbler's yellow, the Pied Wagtail dull yellow, and the Garden Warbler, according to Bettoni, buff. The nestling Hedge Sparrow has two black spots on its tongue, and the Grasshopper Warbler several spots (Macpherson). Probably none of these tints are lost until the young have left the nest.

Anatomy.

Under the heading of "Anatomy," I cannot do better than quote the precise description of Prof. Macgillivray, who in this branch of science especially excelled over other writers:—

"Œsophagus one inch two-twelfths long, inclined to the right, with a distinct dilatation or crop a quarter of an inch in width; the proventriculus bulbiform. Stomach a very muscular gizzard, six and a half twelfths long, seven twelfths broad, obliquely placed, with the lateral muscles very prominent, the epithelium dense, with broad rugæ, and of a yellowish colour, the right muscle two twelfths thick. The trachea as in the Passerinæ and Cantatores; its rings sixty."—(William Macgillivray.)

See also "Remarks on the Internal Structure," by Robert F. Tomes, 'Ibis,' 1860, p. 317.

In Confinement.

Since 1743, when the Countess of Albemarle brought a cageful of Bearded Tits from Copenhagen, it has been popular with bird-fanciers in this country, and the experience of all who have tried it is that it is a bird in every way to be recommended for the cage. There is no need to infringe on our native stock, for continental birds, which, in the opinion of some are finer than British, can be generally bought from Erbermehl, Abrahams, or Zache.

Mr. John Young has written one of the best accounts of this charming species in captivity (Norf. and Nor. Nat. Tr. iii. p. 519), and I am indebted to him for showing me his cage. He first of all provided them with proper nesting places and material, by sticking the tops of pampas grass round a six-inch pot of earth, a site somewhat similar to the reeds of their native haunts. Here the eggs were laid early in the morning, and when the birds had left the nest he invariably found that the lining was pulled over the eggs. Many eggs were laid, two hens laying more than fifty in one summer, a fair proportion of which in a wild state would have been hatched.

Mr. Young thinks they might be hatched, and even the young reared in confinement, by supplying the old birds with the pupæ of the common blow-fly, which he has found to answer with Siskins, and fresh ants' eggs would probably be useful. He kept one nearly five years. Mr. Lowne, of Yarmouth, a well known prize-taker at bird shows, reared six Bearded Tits from the nest on dry ants' eggs with hard-boiled egg well sieved, but they were pugnacious enough to pull each other's tails out, and had to be separated.

Another correspondent, Mr. J.L. Bonhote, had a pair three years, and kept them in an outdoor avairy through the hard winter of 1895. In 1896 the hen built a nest with materials brought her by the cock, and, commencing on April 14th, laid a clutch of seven eggs, two of which were hatched on the thirteenth day, and the young grew well, but died suddenly on the seventh day when beginning to shoot their feathers.[3]

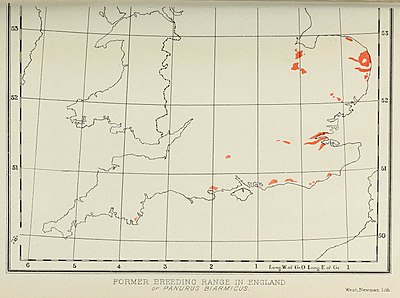

Former Breeding Area.

In the accompanying Map (PI. V.) the pink colour is intended to show where this species formerly bred in England, an area which must always have coincided with the reed beds suitable to its requirements, which, prior to the draining of the great Bedford Level in the early part of the seventeenth century, were much more extensive than they are now. Of the nineteen spots marked pink in the map, only one is still a breeding-place at the present day, which is a somewhat sad reflection; while the old haunts on the Thames have long been deserted, though still sometimes referred to in books.

As it is a good plan to summarise what is known about any British bird's distribution (as Fatio and Studer are doing for Switzerland and Ternier for France), I have given at some length, from such sources as are still available, what can be gathered from authors about the Bearded Tit in the Norf. and Nor. Nat. Trans, vi. p. 429, and the following further particulars may be added. It only breeds in Norfolk, and the only other counties in which it is still to be found with any sort of regularity are Suffolk and Cambridgeshire.

In Suffolk, in March, 1899, a small flock was seen on Fritton Lake and another on Oulton Broad, where, from enquiries on the spot in 1885, I found it was to be met with; and in 1891 Mr. Bunn, the taxidermist, informed me of his having had several from there at different times. Babington gives interesting particulars of their former haunts (Birds of Suff. pp. 64, 251), but they are now extinct on the Blyth and the Alde, but Mr. Tuck was recently informed of some being on the River Lack.

In Lincolnshire the late Mr. Cordeaux never met with a specimen, yet in 1864 A.G. More thought it might breed in that county ('Ibis,' 1865, p. 120), which was one of the five enumerated by W. C. Hewitson. It is certain that when Gould, in 1873, said it bred in all the fenny districts of Lincolnshire, he was entirely wrong. Miller Christy has collected interesting details of its former abundance in Essex, and even thought it possible in 1890 that it might still be reckoned a resident in extremely small numbers, though the last identified seems to have been on the River Stort in July, 1888 ('Birds of Essex,' pp. 91, 92).

In Cambridgeshire, Mr. John Titterton, of Ely, does not know the last date of its breeding, but is able to give the most recent information of migrants, viz. that in 1897 fourteen were seen, and in 1898 a flock of five, and again in December, 1899, a flock of about a dozen, which remained for more than a month in one place. These, however, by the end of January, 1900, had been so upset by the harvesting of the reeds that only three or four remained. In the palmy days of Whittlesea Mere they must have been abundant, but Whittlesea is a thing of the past. A pair obtained there in 1841 are in Newcastle Museum, and it is on record that this locality furnished a white variety.

For Surrey, some additional particulars are given in the 'Birds of Surrey,' by J.A. Bucknill, who remarks that authors have regarded the Bearded Tit as having been a resident at one time in Surrey, but he has not been able to discover any evidence of such being the case.

- ↑ Browne also sent Ray several other pictures of birds ('Willoughby's Ornithology,' preface), but from a subsequent complaint it appears they were not returned (Wilkins' edition of Sir T. Browne's Works, i. p. 337).

- ↑ "Broad" is a local name for a shallow lake often surrounded with reeds, formed by the expansion of a river in former times; a "broad-water" it would be called in some counties, but in Norfolk and Suffolk it is a broad."

- ↑ Mr. Bonhote has just published an article on this subject (cf. 'Avicultural Magazine' for August.)