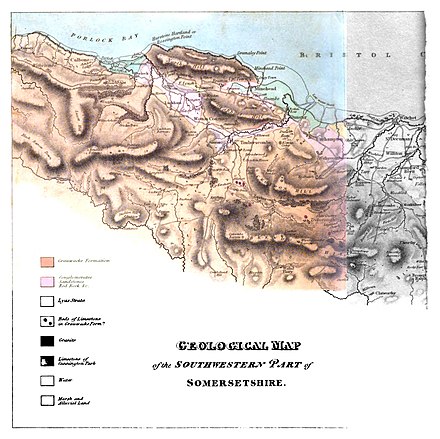

Transactions of the Geological Society, 1st series, vol. 3/On the Geology of the South-Western part of Somerstshire

IX. Sketch of the Geology of the South-Western Part of Somersetshire.

By LEONARD HORNER, Esq. F.R.S.

§ 1. I beg leave to offer to the Society an account of some observations

on the mineralogy of that part of Somersetshire which

lies on the Bristol Channel westward of the river Parret. The shortness

of my stay in the country prevented me from conducting my

examination with that minuteness of detail which an accurate

survey should possess, but I trust that with the assistance of the accompanying

map[1] and the series of specimens which I have deposited

in the museum of the Society, the following notes will be sufficiently

distinct to afford a general view of the geological structure of that part

of England. I have distinguished in the map, by means of different

colours, the situation which the several rocks occupy, and although,

from unavoidable sources of error, the boundaries of each can

only be considered as approximations to the truth, yet I do not

conceive that the inaccuracy in that respect is so great as to affect

any geological deductions.

§ 2. In the western part of Somersetshire, and partly within the adjoining county of Devon, there is a large district of high land, the greater part wild and uncultivated, extending about 30 miles from east to west, and about 16 miles between north and south, the highest and wildest part being known by the name of Exmoor Forest. In appearance and structure it is very analogous to a great part of Devonshire and Cornwall, and may be considered as the termination of those schistose rocks which prevail so much in these counties. It is divided into several ranges of hills, distinguished by particular names, the most conspicuous of which are Dunkery beacon, Brendon hill, Croydon hill, Grabbist hill, North hill, and the Quantock hills. The longitudinal direction of these is, with the exception of the Quantock hills, nearly east and west; there are numerous lateral branches from each central ridge, forming small steep vallies, or gullies, which terminate in the great vallies that divide, and are parallel to the principal ranges. These gullies, called Combes in the country, when richly wooded, form some of the most striking features of the beautiful scenery for which this coast is so celebrated. The Quantock hills, although cut of from the main body of this mountainous tract by a wide cultivated valley, may, in a geological point of view, be considered as strictly belonging to it, for the range itself and the intervening valley are formed of the same rocks as the country to the westward. This apparent insulation, and the peculiar beauty of the range, mark themes a prominent feature in the country; they are no less remarkable from the varied scenery they afford, and the magnificent prospect that is seen from their summit. The name is generally applied in the country, as it is in the Ordnance map, to a range of about eight miles in extent from north-west to south-east, and which is in fact the highest and most conspicuous part. From the south eastern extremity, the mass is divided into several distinct ridges, all composed of the same materials as the Quantock hills strictly so called, and which spread out in the form of a fan, having one extremity at North Petherton, and the other at West Monckton, with a gradual fall to the alluvial land on the banks of the rivers Parret and Tone. On the western side of the Quantock hills the descent is very rapid into the valley; on the eastern side it is in general much less so, and a great many lateral branches stretch out at right angles to the range, shooting off, however, considerably below the summit. These sometimes terminate at a very short distance from the central ridge with an abrupt slope, at other times they descend very gradually almost to the Parret, shewing occasionally at their termination their identity in composition with the central mass.

The whole of the mountainous country I have mentioned has a smooth undulating and rounded outline, no where rugged or presenting any cliffs or precipitous faces, except on the sea shore, where sections have been formed probably by the action of the tides. The whole country is so covered by vegetation, either in the form of heath and turf on the high land, or of the more luxuriant productions of the vallies, that very few opportunities occur in the interior of ascertaining the nature of the rock on which the soil rests; but the cliffs on the sea shore afford such an ample field for studying the mineralogical structure of the country, that the scattered observations in quarries, may be more strongly relied on and more easily connected.

§ 3. From the Parret to Barnstaple Bay there is no river of any magnitude: the great watershed is to the south, and the Ex, one of the most considerable of those rivers which fall into the English Channel, rises in Exmoor Forest. The southern shore of this part of the Bristol Channel is very steep, the sea in many parts not leaving the cliffs in the lowest tides. From Minehead Point westward, the charts give 8, 9, and 10 fathoms water close in with the shore. Eastward of that point the coast is more flat, and towards the mouth of the Parret the distance between high and low water mark is in some places above two miles. From the town of Minehead there is a tract of low marsh land, extending eastward about four miles along the coast, and about a mile in breadth in most places from the sea to the base of the hills. Were it not for a bank of pebbles which the sea has thrown up on the beach, this land would be overflowed every tide; and this even now generally occurs when the tides are unusually high. A similar tract of marsh land occurs in Porlock Bay, which is equally protected by a very great shingle bank, divided into three terraces rising the one above the other, the highest part of the bank being not less than forty feet above low water mark. The pebbles, which all along the shore are of the same materials as the cliffs in the open part of Porlock Bay, are of various sizes, but they are in general flattened spheroids of about six inches in diameter; as they approach the cliffs at Hurstone Point, they become gradually less, and close to the cliffs, they are of the shape and size of a pigeon's egg, and nearly all alike.

Dunkery beacon is stated in the report of the Ordnance Trigonometrical Survey to be 1668 feet above the level of the sea, and, with the exception of Cawsand beacon, in the northern part of Dartmoor Forest, which is stated in the same report to be 1792 feet, is I believe, the highest land in the West of England.

Grabbist hill I found, by barometrical measurement, to be 906 feet above low water mark. The highest part of the ridge is immediately above the village of Wotton Courtney. I made use of Sir Henry Englefield's mountain barometer, and I have calculated the heights by the formula he gives.

North hill above Bratton, which appeared to me the highest part of that ridge, I found to be 824 feet above low water mark. The western extremity, which I did not measure, judging from its appearance at a distance, can be very little less than this height.

The Quantock hills when viewed from a distance, present a gently undulating outline, which rises in three places into a more prominent elevation, the most northern being called Doucebury,[2] the central height Will's Neck, and the most southern Cothelstone Lodge, from which last point the range diverges, as has been already noticed. Will's Neck is the highest of the three, and was measured at the time of the Trigonometrical Survey, and found to be 1270 feet above low water. It is called in the Survey the Bagborough station, being immediately above the village of that name. Doucebury I found by the barometer to be 1022 feet, and Cothelstone Lodge 1060 feet above low water mark; but as both these measurements were made under very unfavourable circumstances, they are not to be relied on. Doucebury must be considerably higher than I found it to be; the measurement of Cothelstone Lodge is probably not very far from the truth, judging in both cases from the comparison between the three heights when seen at a distance.

§ 4. The whole of the mountainous part of this district is formed of a series of rocks differing very considerably in mineralogical characters, but which the repeated alternations of the several varieties, and the insensible gradations that may frequently be traced of one into another connect into one common formation. A great proportion of these have the structure of sandstones, the component parts varying in size from that of mustard seed to such a degree of fineness, that the particles can with difficulty be discerned. Quartz and clay are the essential component parts of all the varieties, but in different proportions. The quartz in some instances prevails to the entire exclusion of any other ingredient, forming a granular quartz rock: it is more abundant in the aggregates of a coarse grain, clay being the chief ingredient in those of a close and fissile texture. They have all an internal stratified structure, which is less apparent in those of a coarse grain, (and in a cabinet specimen scarcely discernible) but which becomes gradually more distinct as the texture becomes finer, and at last the rock graduates into a fine grained slate, divisible into lamina as thin as paper, and having the smooth silky feel and shining surface of the clay slate of a primary country. Alterations of the fined grained slaty varieties with those of the coarsest structure in many successive strata and without any regularity of position, are of constant occurrence, and frequently without any gradation from one structure into the other.[3] In some instances portione of slate are contained in the coarse grained varieties. Scales of mica are frequent, and they all contain oxide of iron in greater or less proportion, and to the different states of this oxide their various colours are, no doubt, to be ascribed. The prevailing colours are reddish brown and greenish grey, and there are many intermediate shades and mixtures of these colours. Some of the slaty varieties are of a purplish hue, and this is occasionally spotted with green. Of the specimens I collected, those of a coarse grain and of a dark reddish brown colour, do not effervesce with acids; those of a pale reddish brown colour, and of a greenish grey colour, all effervesce, and some of them briskly. None of the varieties of slate shew any signs of effervescence. The magnet was not affected by any one of the series. I did not discover a trace of any organic body in either variety, but in many places great beds of limestone full of madrepores, are contained in the slate, the limestone and slate towards the external part of the beds being interstratified. Veins of quartz, which are often of great magnitude, are of constant occurrence, being sometimes accompanied by calcareous spar and ferriferous carbonate of lime; veins of sulphate of barytes are not uncommon. Thin layers, composed of quartz, chlorite, and ferriferous carbonate of lime, are often interposed between the strata of slate, and pyrites is sometimes disseminated through the mass of the rock. Copper, in the state of sulphuret and of malachite, and veins of hematite, are frequently found, and nests of copper ore of considerable magnitude have been found in the subordinate beds of limestone.

Those who are acquainted with the geology of Devonshire and Cornwall will recognize in these characters a great similarity between the rocks which I have been describing, and those which form so large a portion of the western counties, and which have of late been designated by several mineralogists by the term grauwacke. I am fully aware of the unwarrantable extension of this name, and of the great want of precision which has been the consequence of applying it without pointing out the mineralogical structure of the compound; but I feel in common with many others the difficulty of finding a less objectionable term by which the series of rocks in question may be distinguished, when it is necessary to speak of them collectively. As the word by itself conveys no theory, and as these rocks have a closer connection with that class to which the term was originally applied than with any other, I shall call the series of rocks which I have described, a grauwacke formation, hoping that the description I have given will, in some degree, remove that want of precision which is the chief objection to the word. To those however who may give to it the theoretical meaning which this word implies in the Wernerian system, I must again point out the alternations of quartz rock, and of a clay slate, with beds of limestone full of organic remains. The clay slate cannot be distinguished from that of a primitive country.

§ 5. A reference to the accompanying map will serve better, than any description to shew the extent of country occupied by this formation: it remains for me to point out some of those circumstances connected with it which appear to be worthy of more particular notice.

The north hill which extends along the shore from Minehead to Porlock, forming a very hold and precipitous coast, affords the best opportunity of studying this grauwacke formation. At Greenaley point, about a mile westward of Minehead, there are very lofty sections where the alternations of the different varieties may be distinguished, and where there are also very good examples of these curvatures, which, in this formation, are of such frequent occurrence. Strata that run for some distance in a horizontal line suddenly turn up into a vertical position, at other times they assume the form of an arch or a succession of great curves. It is hardly necessary to say that these rocks could not have been deposited in the forms they new exhibit, and it is pretty evident that the flexures must have taken place while the rock was in a plastic state, for there is no fracture at the bendings, nor any interruption to the continuity of the mass. Similar curvatures are to be seen at Hurstone point, the western extremity of North hill. These appearances are so well known that drawings of them are unnecessary: they are very analogous to those observed by Mr. Conybeare in the same rocks on this coast, some miles westward, and represented in the 33d and 34th Plates of the 2d. Volume of the Society's Transactions.

§ 6. In every part of the district where the slaty varieties prevail, the ends of the inclined strata as they rise to the surface become either vertical or are very much twisted. Here however the contortions appear to have taken place after the induration of the stone, for they are not in the form of curves, but are in general a succession of sharp angular twisting, with a fracture at every angle. The strata in general as they approach the surface are also very much traversed by those imperceptible cracks which make the rock, as soon as it is moved from its bed, break down into polygonal fragments of various dimensions. Hence are probably derived those loose fragments which are to be found under the surface soil all over the district where this formation occurs, and even at the summits of the highest hills. In the ravines formed by the streams in the lower parts of Dunkery beacon, there are sections of some yards in depth where nothing is seen but these fragments, imbedded in a loose red sandy soil, which is doubtless produced from the decomposition of the fragments themselves. The angular shape of the fragments is an additional proof that they have been produced on the spot, and that they are not materials transported from a distance. The most remarkable instances of these angular contortions are to be noticed in the lanes between the village of Enmore and West Monckton, and the other roads which cross the south-eastern ridges of the Quantock hills. I may particularly point out the neighbourhood of Adsborough, and the lane leading to Tarr near Kingston, where the ends of the strata of slate are covered by horizontal beds of red argillaceous sandstone and of conglomerate.

§ 7. In a country covered by vegetation, and where the rock is so liable to partial irregularities, it is exceedingly difficult to form any general conclusions as to the bearing and dip of the strata. Every geologist must have observed that the external shape of a hill is not always a certain guide in determining the bearing of the strata that compose it, and that in many places other causes must have operated in producing the external forms which the earth now exhibits. I believe however that the general bearing of the strata in question may be stated to be between east and west, and that the dip is more generally to the south than to the north.

§ 8. In the ridge which terminates at North Petherton, there are at Binfords some very large quarries where the gradation of one variety of rock into another may be seen. In the lower part of one of the beds there is an accumulation of rounded masses of an oblong shape, varying in size from a few inches to several feet, in the direction of what may be termed their longest diameter. Their internal structure is often identical with the adjoining strata of grauwacke, but they more frequently consist of a succession of thin concentric layers, these layers being of the same substance with the strata, but separated from each other by a thin coating of oxide of iron, having the shining lustre of hematite. The smaller of these masses more nearly resemble a large mytilus than any other shape to which I can compare them, and the larger of them preserve nearly the same form. They appear to have been consolidated while the rock in which they are imbedded was in a soft state, for the surface of the bed on which they rest is covered with the moulds of those that have been removed.

§ 9. Near Ely Green in the side of a combe called Dibbles, towards the summit of the Quantock hills, I observed a variety of slate differing considerably in appearance from any I met with in the district except in one other spot. It is of a bluish green colour, apparently derived from chlorite, with purplish stains and including small spherical masses of a white earthy texture, which give to the mass an amiygdaloidal structure: it may be considered as a variety of argillaceous slate, and as it occurs in strata conformable with the usual varieties of the grauwacke formation, it belongs I have no doubt to the same class: it is found to be very useful as a fire stone. The other place where I found a slate very similar to this was in the neighbourhood of Cheddon Fitz-Paine.

§ 10. In passing through the village just named, I observed in the street a small block of stone differing in appearance from any I had found previously, and upon examination I found it to be granite, a rock I had searched for before without success, and indeed this is the only place where I saw an unstratified rock in the whole district, the porphyry and greenstone which accompany the grauwacke formation in Devonshire being wholly wanting here. On inquiry I found that this granite, called by the country people Pottle Stone, came from an old quarry not far distant in the grounds of Hestercombe, belonging to T. Warre, Esq. My informer brought out of his house a whetstone which he said came from another quarry close by the Pottle Stone. It was a greenish compact stone, very like some hornstones or some of those close-grained siliceo-argillaceous compounds which it is very difficult to name. On going to the quarry, which is almost entirely over-grown with brushwood, I found the granite in situ: it is small grained, and consists of dull flesh-coloured felspar, with green mica, and a small quantity of quartz. It occurs in the lower part of the hill and occupies very limited extent. Immediately adjoining is the spot where the whetstones are got. Here I found I regular strata of slate similar to that occurring in many parts of this district, inclined at a considerable angle and rising towards a mass of the granite which appears in the form of a wall a few feet above the ground. Within a few yards of the granite the inclination of the strata is about 35°, but as it approaches nearer to it the angle increases to 63°, and the texture of the stone becomes much more compact; the actual junction of the two rocks is, as is usually the case, very indistinct, the stratification of the slate being very much disturbed and broken: but I was informed that the best whetstones are got nearest the granite, and I found the most indurated pieces in that situation. Being desirous of seeing the actual contact, I obtained permission from Mr. Warre to clear away the ground across the line of junction: and although the quantity of brushwood, and thick covering of soil, and a very unfavourable state of the weather prevented me from making so complete an examination as I wished, I so far effected my purpose as to find the junction. The granite as it approaches the slate becomes much finer grained than before, and at the contact there is an indistinct blending of the two, and as far as I can judge from the very imperfect specimens I could obtain, there is an appearance of fragments of the slate united by a granitic cement. All the circumstances appear to favour the supposition of this being a vein of granite, but the evidence I have to offer is too scanty to enable me to speak with confidence on the subject.

§ 11. Some years ago a shaft was sunk in one of the branches of Grabbist hill at Stanton, above the village of Alcombe, in consequence of some indications of copper in the rock there, but the quantity of one found was so small that the workings were very soon given up. I found among the rubbish some pieces of green carbonate of copper with grey copper. Similar trials with no better success were made at Perry near the northern extremity of the Quantock hills. I found there, among the rubbish, specimens of malachite and of brownish-black sulphuret of copper.

I received from Thomas Poole, Esq. of Nether Stowey, a specimen of an exceedingly hard and compact iron ore which had been found in the Quantock hills, but in what place he could not inform me. It is an oxide of an iron-grey colour and semi-metallic lustre, with a sharp splintery fracture, and so hard as to scratch glass easily. Its specific gravity I found to be 5.244, which with its other characters brings it nearer the fer oligiste of Haüy than any other variety of ore. The occurrence of so rich an ore in a large quantity, would be a very valuable discovery.

§ 12. In several parts of this district there are found, as I have already stated, very considerable beds of limestone which are contained in the slate. Their occurrence in detached spots, and their appearance in the quarries where they are most extensively wrought, seem to point out that they are not regular strata conformable with those of the slate above and below them. Flattened spheroidal masses of the same kind of limestone are frequently found, completely enveloped by the slate, and very similar to the balls of clay-iron-stone in slate clay, but thinning away at the edges much more than those do. I conceive that the great masses of limestone occur in the same way: they have an irregular bedded structure, and very often layers of slate, often of considerable thickness, are interposed between the beds; but although the positions of the quarries along the eastern side of the Quantock hills appear in a continuous line on the map, the great variations in the bearing and dip of the strata of those quarries renders it extremely improbable that the limestone of each, although very similar, are parts of regular strata. These beds of limestone appear to be confined to the places where the slaty varieties of grauwacke formation prevail; I shall now point out some of the most extensive quarries where they are worked.

§ 13. At Allercot, about four miles south of Minehead on the road to Dulverton, the principal bed of limestone is 30 feet thick. It is of a bluish grey colour, variegated with red, of a crystalline structure, and full of small laminæ of calcareous spar disseminated in detached spots through the mass, which are most probably the remains of organized bodies. Besides this great bed, there are several others of less thickness contained in the slate, and the thinner beds are of an iron-grey colour. The slate is one of those line grained varieties which approach very nearly in appearance to the clay slate of a primary country; it is very much contorted, and the curvatures are often so small as to be seen in a cabinet specimen. Is is very much traversed by veins of quartz. I was informed by the workmen at Allercot that there are quarries of a similar kind of limestone at Westcot, Treborough and Leigh. At Treborough a very excellent roofing slate is obtained.

§ 14. At Doddington, Friern farm, and Ely green, on the

eastern side of the Quantock hills, the quarries are very extensive.

In those of Friern farm I found some of the beds to be a very close

grained crystalline limestone without the slightest appearance of any

organic remains; but upon a close examination of the stone when

broken in different directions, and particularly at those places where,

it is bruised by the stroke of the hammer, I found many parts of

the bed to be almost entirely composed of a madrepore. Towards

the exterior, madrepores are very distinctly seen, and in some of

the beds the stone is full of circular bodies composed of large

crystalline plates of calcareous spar, which I have little doubt are

entrochi, but I did not discover a shell any of description.

§ 15. In the quarries at Great Holwell there may be seen on a small scale that occurrence of caverns so frequent in limestone. They vary in width from half a foot to five feet, and their height varies with the thickness of the beds. In some places they may be seen to close, but in general their depth was beyond what I could ascertain. Their sides although uneven by the irregular projections of the rock have all a smooth rounded surface, as if worn by attrition, but this seems to be owing to an incrustation of calcareous spar which hangs down in many places in large stalactites, a process that is evidently going on at the present time in several of these caverns. That the caverns have not been produced by any rents that might have occurred after the consolidation of the strata, is evident from their being confined to the limestone and not extending through the intervening slate.

§ 16. Nests of copper are very frequently found in this limestone. I observed in several places small nodules of the green carbonate enveloped by brown ochreous earth. At Doddington a very large quantity was found some years ago. A loose friable quartzose sandstone, which I shall afterwards notice, was found to contain so much copper ore that a mine was sunk in it. In order to drain the works which were situated upon the rise of the hill, a shaft was sunk for the purpose of driving a level from north to south up to the workings, expecting at the same time to cut across any veins of metal that might exist there, as they are generally supposed in this part of the country to run east and west. They had proceeded a very short way in driving this level when they came upon a blast slaty limestone, and immediately afterwards they found a large nest of copper ore, consisting of the green carbonate, and yellow sulphuret. The workings in the sandstone were immediately given up; they did not continue driving the level, but worked in the limestone on all sides The mine has however been abandoned, as the produce was not sufficient to bear the expense of an engine to drain off the water.[4]

§ 17. I found specimens of the black slaty limestone at the mouth of the pit, and I afterwards observed the same stone in the limestone quarry near Ely green interposed between the beds of limestone. It is of a coal black colour, but becomes white when heated: dissolved in muriatic acid it leaves a black powder, and this powder when heated is partly dissipated, and what remains is a white earth. The limestone appears therefore to owe its black colour to carbonaceous matter.

Besides the quarries I have named there are several others, but as they present no appearances different from those I have already described, it is not necessary to do more than mark their occurrence on the map.[5]

§ 18. About a furlong eastward of Halsey cross, in a quarry

where stones are obtained for mending the roads, I found strata of

the coarse grained and slaty varieties of the grauwacke formation,

alternating with a calcareous rock different from any other I had

seen in this district. Its colour is in general reddish brown, very

similar to the strata that alternate with it, but the calcareous strata

are not all alike. In none of them are there any traces of organic

remains, unless indeed some detached crystalline laminæ may be

considered as indications of them. The principal varieties are

1. A crystalline limestone which burns to a white lime mixed with brown spots, falling very readily to powder. 100 grains dissolved in dilute acid left 7 grains of residuum, which consisted of about 4 grains of oxide of iron, the remainder being silica.

2. The preceding variety mixed with a considerable quantity of quartz, and of yellow calcareous spar. This latter substance occurs also in veins and probably pervades all the calcareous strata. A piece of that stone when thrown into dilute acid leaves a fragment which does not fall into powder.

3. This variety is intermixed with a smooth slaty substance with an unctuous feel, which is probably talcose slate: it leaves: considerable quantity of large grains of quartz when thrown into dilute acid.

None of these calcareous strata are used for any other purpose than to mend the roads, and they do not seem to be known as limestones, most probably because there is a much better limestone so near at hand. The first variety would yield a very good lime, if reliance for that purpose can be placed on my minute experiments; a trial on the large scale might very easily be made in one of the neighbouring lime kilns. The principal calcareous stratum is five feet thick.

Immediately behind the village of Bagborough I found a calcareous stratum occurring in the same way as those at Halsey cross.

§ 19. My observations were principally confined within the limits I have already mentioned, but having had an opportunity of making a cursory examination of the country between Porlock and Ilfracombe, and as the rocks occurring in that part of the country are connected with those I have been describing, I shall briefly state the few notes I made. My route was from Porlock, by Culbone, Withycombe farm and Countesbury to Linton, and from thence through the Valley of Rocks by Slattenslade, Trentishoe, Combe Martin and Berry Narbor to Ilfracombe. A very great part of this country is entirely concealed by vegetation, but wherever the rock is exposed I found some variety of the grauwacke formation identical with those I had left behind. In that part of the road which is eastward of Linton, the coarser grained varieties are most frequent, but westward of that place the slaty varieties predominate, very often resembling some kinds of iron-grey clay-slate found in primary countries. Towards Ilfracombe this appearance becomes still more decided, and in a cabinet specimen it would be impossible to tell the difference. But beds of limestone with very decided indications of organic remains contained in this slate, show that it is of secondary formation, and at the same time afford a useful lesson of the inadequacy of mineralogical characters alone to determine the geological nature of a rock. These limestone beds are found between Berry Narbor and Hele; their resemblance to those I have described in the former part of this paper both in internal composition and in the accompanying slate, leave no doubt of their belonging to the same class. When struck with a hammer it emits a slight bituminous smell, a circumstance which I did not observe in the limestone of the other places I have mentioned, and it is traversed by very large veins of a transparent and very beautiful calcareous spar.

§ 20. Throughout the whole district described in this paper I found the grauwacke formation surrounded either by a conglomerate, or by a red sandstone, sometimes tolerably compact, but more frequently of a friable texture. These conglomerates and sandstones assume very various appearances, but under every form of aggregation the same materials may be traced. Where the component parts are large, as in the conglomerates, the nodules consist of some of the varieties of rock that compose the grauwacke formation; and in many places there are nodules of a limestone very similar to that of the subordinate beds in the same series. These derivative rocks under one form or another are found in all the intervening valleys, and the great valley on the western side of the Quantock hills is wholly composed of them. They are not however confined to the vallies, but are sometimes found on the sides of the hills at a very considerable elevation. It would have been a fruitless task to have attempted to distinguish in the map each particular form of aggregation, more especially as I did not discover any uniformity in their relative positions. I have thought it better to class the whole under one head and to represent them as such by one colour. It will be necessary however to point out in detail some of the most remarkable instances.

§ 21. In the eastern and highest part of the valley in which the village of Porlock is situated, there is found at Tivington, Huntsgate and Holt farm, a conglomerate composed of thin fragments of a coarse grained slate seldom exceeding an inch in size, with pieces of quartz, cemented by white calcareous spar. The surfaces of the fragments are rounded by attrition, and are coated with reddish brown oxide of iron, which has in many places the metallic lustre of hematite. The fragments are in some places so small that the rock has the appearance of a sandstone. It occurs in thick beds which are often inclined at a considerable angle, but not conformable with the slope of the hill in the lower part of which the conglomerate is found. The smaller grained rock frequently alternates with the coarse conglomerate: at Tivington the latter variety prevails, but at Huntsgate that resembling a sandstone forms the thickest beds. Both varieties are very much traversed by veins of calcareous spar. At Holt farm there is a vein nearly 18 feet thick, consisting of several layers so distinct that I at first conceived the mass to be a series of strata, but upon further examination I found that it was inclined at right angles to the dip of the beds of conglomerate. It is stratified not only on the great scale, but also in the internal structure, which consists of a succession of layers, having in many places a waved appearance similar to that seen in sections of recent calcareous depositions. Part of this vein consists of a mixture of white, red, and honey-yellow calcareous spar, resembling in some places cellular quartz. The quantity of calcareous matter in this conglomerate is so great that it is quarried for the purpose of obtaining lime from it. But at Holt farm, the great size of the vein renders it unnecessary for them to use the less pure conglomerate.

§ 22. In the lane leading from the town of Minehead to the church, which is situated near the eastern termination of North hill, the rock has been cut through to a considerable depth. At the first part of the ascent it is a friable red sandstone distinctly stratified, and dipping north-east by north about 15° as it were into the hill. It is almost entirely siliceous, and contains no calcareous matter, not are there any of those grey patches which generally accompany the marly red sandstone to be afterwards described. It appears to rest upon a conglomerate, that rock just appearing above ground. Continuing to ascend, this red sandstone after a short way is suddenly broken off, and is succeeded by a conglomerate which continues during the remainder of the ascent, till it meets the grauwacke formation immediately above the church: unfortunately the actual contact is not exposed. This conglomerate consists of rounded fragments of rocks identical with those found in the grauwacke formation, but without any limestone. In different parts of it there are patches of the same red sandstone that occurs in the first part of the ascent, varying from a few inches to several fathoms in extent, and having in general a stratified structure.

§ 23. Near the village of Alcombe, and at the foot of one of the lateral branches of Grabbist hill, there is found a conglomerate differing considerably from either of those already described. It occupies a very small space superficially, probably not more than a square furlong, but it is found in very thick beds. It is composed of rounded fragments of the coarser quartzose varieties of the grauwacke series, of limestone and of quartz, united by a calcareo-argillaceous cement of a reddish brown colour. The limestone is in general grey with a reddish tinge, of a crystalline texture, with laminæ of calcareous spar scattered through it, and frequently containing carbonate and sulphuret of copper; characters sufficient to identify it with the subordinate beds of the grauwacke formation. In one or two instances I found it containing chert. In some parts of the conglomerate the cement is very much mixed with white and flesh coloured sulphate of barytes in crystalline plates, and with green carbonate of copper. It is also traversed by veins of calcareous spar, and contains cavities lined with crystals of the same substance. The fragments are of different sizes; some of them are as large as a man's head. The conglomerate is covered by a loosely aggregated quartzose sandstone, varying in colour from reddish white to brownish red, and often containing much calcareous matter. Sometimes there are fragments of the same varieties of grauwacke that occur in the conglomerate, found in those parts of the sandstone that are contiguous to it; and it is also mixed in some places with green carbonate of copper and with sulphate of barytes. In the upper part of the conglomerate there are rounded fragments of a sandstone mixed with carbonate of copper nearly identical with that of the beds lying over the conglomerate. This sandstone is about 5 or 6 feet in thickness, and dips northward about 18°. The signs of stratification are not very distinct in the conglomerate, but the beds appear to dip at the same angle and towards the same point as the superficial sandstone. This conglomerate is called Popple rock (Pebble?) by the quarries, and is worked on account of the nodules of limestone, which are picked out and made into lime.

§ 24. Opposite Bickham farm near Timberscombe, and at the foot of the hill which may be considered the eastern termination of Dunkery beacon, another modification of the conglomerate occur. It is composed of large irregularly-shaped flat masses of limestone imbedded in a pale green sandy clay. Between these masses there is interposed a conglomerate of smaller sized fragments, very analogous to that found at Tivington, and the whole series is covered by a friable red marly sandstone. The limestone is similar to that found in the conglomerate at Alcombe. The lower part of the valley on the south side of Grabbist hill is chiefly meadow land, but in some places where the ground is broken, as in the road near Wotton Courtney, and in the road from Timberscombe to Minehead, I observed a red marly sandstone with grey patches containing thin strata of a small sized very compact breccia composed of fragments of a white indurated clay, united by a cement of clay mixed with calcareous matter, and here and there small cavities in it lined with calcareous spar. This compound I did not find in any other part of the district.

§ 25. The valley which separates the Quantock hills from the mountainous country to the west does not present a uniformly even surface: there is along its whole extent a succession of low hills having a longitudinal direction parallel to that of the valley. There are two ranges of these hills, but the most conspicuous are on the side of the Quantock hills. The whole of this valley is occupied by the derivative rocks I have been describing, and all the different modifications to be found in the district occur in this valley, and the whole of the low hills are composed of them. In the bottom of the valley there is a considerable tract of loose sand. On leaving the grauwacke series near Dunster, we find at Carhampton a low hill composed of a red argillaceous sandstone, and proceeding eastward towards Williton, either that sandstone, or a sandstone containing rounded fragments of the grauwacke formation appears in all those places where the ground is broken. At Tarr, Tor Weston, and Vellow, the same conglomerate (or pebble rock) that I have described at Alcombe, again appears. At Tor Weston the quarries are situated near the top of a small detached hill, the conglomerate forming beds of great magnitude. At Vellow there are sections of it above 50 feet in height, and it rests here upon a bed of red clay. There are distinct parallel lines which divide it into thick beds, dipping northward about 10°. It contains here more fragments of limestone than it does at Alcombe, and I found between the pebbles in some places, small nests of hematite. It is covered as at Alcombe by a sandstone, but of a different variety, being of a deep reddish colour and full of fragments of grauwacke, and without any appearance of copper or of sulphate of barytes. The same sandstone may be seen in different places between Williton and Vellow, particularly near the village of Sampford Brett. A little to the west of Williton church, there is a reddish white sandstone, much harder than any other I met with in this district. It occurs at the eastern termination of the same ridge, on the west side of which the quarries of conglomerate at Tarr are situated, and I think that it is very probably only a variety of that sandstone which covers the conglomerate in other places. If it is stratified the lines of separation are very indistinct. There are many perpendicular fissures in it; part of which are filled with a pulverulent carbonate of lime. It is very durable when used for building, and Watchet Pier has been repaired with it. The Popple rock of Vellow extends as far as Yard farm, and I observed it in the road near Quark-hill farm on the eastern side of the brook.

§ 26. At Lawford farm near Crowcombe there are some large quarries where different varieties of the derivative rocks may be seen. The conglomerate, besides its usual component parts, is accompanied by patches of a green sandy clay, similar to that in the quarries near Timberscombe, and I may remark here that these green patches are prevalent in almost all the forms of conglomerate on the south and south-east slopes of the Quantock hills.

The conglomerate at Lawford farm is covered by several beds of red sandstone, which are in general separated from each other by a layer of rounded fragments of grauwacke mixed with red earth. There are also several beds of conglomerate which are separated by beds of sandstone, lying nearly horizontal: some of the sandstone beds give more lime than any other in the quarry. This series of beds extends for some distance towards Lydeard St. Lawrence by Crowcombe Heathfield, and is succeeded near that town by red sand.

§ 27. A road is carried along the side of the Quantock hills from Crowcombe to Bagborough by Triscombe. The derivative rocks prevail all along this road, although it is at a very considerable elevation: this is the greatest height at which I found them, except in one place on the eastern slope of the Quantock hills, and near the summit of the range, at Quantock farm; where in digging a foundation there was found below the surface soil a conglomerate, consisting of rounded fragments of grauwacke cemented by a deep red clay, forming a mass of extreme hardness. A short way south of Triscombe the conglomerate appears, and may be traced to Bagborough and from thence the whole way to Bishop's Lydeard, where sections of it are seen in the side of the road.

§ 28. I have every reason to believe that nearly the whole of the rich vale of Taunton Dean is formed of rocks of this description. Mr. De Luc[6] describes a “ red marl with blue stripes” between Blackdown and Wellington, and in the neighbourhood of Wiveliscombe he observed “ at the summit of two eminences” a conglomerate in all respects the same as the Popple Rock of Vellow, which he afterwards examined.

§ 29. Near the village of St. Michael the road is cut across a ridge, and exposes a section of conglomerate and red sandstone to the depth of 20 or 30 feet, and the same rocks are found in all the intervening vallies between the ridges of the grauwacke formation which extend from Cothelstone Lodge in a south-easterly direction. The road from Bridgwater to Nether Stowey crosses the extremities of some of the lateral branches that extend from the Quantock hills, and these are entirely composed of the derivative rocks. Near Cokehurst, at a place called Mount Radford, there are some large quarries where a very hard conglomerate is worked. In composition and alternation with sandstone it is very like the series at Lawford farm, and like that contains green patches. It occurs in thick beds which are inclined at an angle of 15°. dipping north by west. In one of the quarries I observed a slip in the beds of about four feet, and the sides of the slip were covered with a smooth coating of oxide of iron similar to a slickenside. Within a mile of Stowey, where the road turns off to Taunton, there is a sandstone which is principally white, but is in some places variegated with red spots and stripes, and containing some of those green patches so general in the conglomerate. In some places it is very friable, in others it forms a hard stone, in thin strata dipping gently to the north and following the inclination of the hill. Near Bincombe and Doddington it is also found, and in both those places it is very white and friable, and contains a great deal of green and blue carbonate of copper, the latter often beautifully crystallized. It was in this sandstone that the mining near Doddington, already mentioned, § 16. was begun. Near Ely Green it is mixed with large red patches, which are very argillaceous, and are chiefly composed of angular fragments of grauwacke; at the bottom of the section the sand becomes more compacted and seams of stratification are distinct. This sandstone I conceive to be the same as that which lies upon the conglomerate at Alcombe.

§ 30. Besides the conglomerates and the sandstone that accompany them, there is a member of the same series which requires to be more distinctly pointed out. It is a red argillaceous sandstone, containing a variable quantity of calcareous matter, but its most characteristic feature is its being always accompanied by spots and stripes of a greenish colour. These greenish parts are of all sizes, from a mere speck to such a degree of magnitude that they often exceed the red portion of the rock, and when this is the case they become much more indurated, and contain a larger proportion of carbonate of lime. There is seldom any marked line of boundary, the passage from the red to the greenish parts being quite gradual: it is occasionally variegated with yellow, and those places abound with dendritical delineations of manganese. It is of a uniformly fine texture, and I never found it to contain any fragments, either angular or rounded. It is the same rock which covers so great a portion of the Midland counties of England, which contains the gypsum of Derbyshire and Staffordshire, the salt mines of Cheshire, and the brine springs at Droitwich in Worcestershire, and which is known by the name of red marl, red ground, &c. There are few rocks which present a greater variety of forms of aggregation, and about which there are so many contradictory opinions respecting its relation, in point of position, to the other secondary strata that lie contiguous to it. To investigate the mineralogical and geological history of this rock would be a most useful inquiry, and not merely as a matter of science, but in an economical point of view, from its intimate connection with the coal formations. There is undoubtedly in the district I am now describing an appearance of this rock having a common origin with the other varieties of the derivative rocks, as a series could without difficulty be collected, shewing an insensible gradation from the one to the other, and the patches of greenish sandy clay I have mentioned in the conglomerates § § 24, 26, are another strong point of resemblance. It never has been ascertained, I believe, what is the chemical difference between these greenish grey patches, and the red rock into which they seem to graduate. In many other places this red marly sandstone is accompanied by similar conglomerates, and I observed in the collection of my friend, G. B. Greenough, Esq. a specimen from Alderley Edge, in Cheshire, identical with that variety of conglomerate found at Alcombe, § 23, which contains sulphate of barytes, and carbonate of copper.─Although I found it always above the conglomerates in this district, I am informed by Mr. Greenough, that this is by no means a general rule. In that part of the district which I have already described it occurs to a very limited extent in point of thickness, but on the sea shore in the neighbourhood of Watcher, it forms, as I shall presently shew, a very prominent feature in the mineralogy of this part of the country. I found it in almost every situation where the derivative rocks occur, and at their greatest elevation as at Smokeham, Crowcombe and Bagborough, but it appears to lie always above them. I did not find it in any one instance covered by the conglomerates or their accompanying sandstones.

§ 31. In the eastern part of the district near the banks of the Parret below Bridgwater there is a nearly insulated hill called Cannington Park, totally different in structure from any other part of the country described in this paper. On the north side it rises directly from the marsh land, with a gradual slope, to the height of 232 feet above the plain: on the south side it is not altogether cut off from the lateral branches of the Quantock hills. It is composed of a highly crystalline limestone, of a pearl grey colour, having a very close grain, and when struck, giving a ringing sound like that of glass. I examined it with very great care, in order to discover whether it contained any organic remains, and particularly at the decomposed surfaces, and in those places where the stone was bruised by the blow of the hammer, which generally detects any madrepores that exist in a limestone, but I could not find the slightest trace; and some of the quarries who had worked there for several years, told me that they had never found any thing of the kind. It contains here and there contemporaneous veins of a very pure white and opake calcareous spar, and the strata are traversed by large veins of calcareous spar. In the latter veins the spar is distinctly crystallized, and in layers parallel to the sides of the vein, a circumstance which points out a marked difference between them and the veins of contemporaneous formation. On the north side of the hill there is a vein of red sulphate of barytes, about three feet thick in the widest part. This substance is not contiguous to the limestone, but is accompanied on each side by a reddish brown ochreous earth. Nor does the vein itself appear to intersect the limestone, but to be interposed between two vertical masses. The barytes contains copper pyrites and green oxide of copper, and in the limestone near the vein I found quartz crystals scattered through the mass, giving it an appearance like a porphyry. I also observed in some places traces of carbonate of copper in the limestone.

§ 32. In going over the top of the hill (which is very much covered by vegetation) the ends of the strata appear above the grass in many places in a vertical position, and running between north-east and south-west, but on coming to the quarries where the rock is extensively exposed, I found that although it is evidently stratified, it is so shattered and so crossed by rents in every direction, that it was impossible for me to discover what were the true planes of stratification, the internal structure of the stone affording no indication. Judging however from the more general direction of the masses, I think they may be said to be either for the most part vertical, or at least very highly inclined and running between north and south. I did not discover the least appearance of slate or any circumstance that could connect this limestone with the subordinate beds in the grauwacke series of the neighbouring hills, except its proximity to them. It more nearly resembles the Plymouth limestone than any other I am acquainted with, and although that has been found to contain both madrepores and shells, there are great portions of it where no traces of organized bodies can be discovered. It is also very probable that by a more minute examination they may be found in the limestone of Cannington Park, for it has certainly very much the appearance of what is called a transition limestone, and there are laminæ of calcareous spar dispersed through it, which are strong indications of organic remains. It produces a very pure white lime, which is carried to a great distance.

§ 33. From the termination of the marsh land which lies to the east of Minehead to that at the mouth of the river Parret there is a rocky shore, bounded by precipitous cliffs, rising in many places to the height of 100 feet. These are chiefly formed of that variety of secondary limestone, so well known by the name of lyas, together with the red argillaceous rock described § 30. The boundaries of these rocks will appear by inspecting the map, and I shall now point out the more remarkable circumstances connected with each. The great disturbances which have taken place in the strata render it extremely difficult to ascertain with precision the relative positions of these two rocks. When I first examined the coast, I observed what I conceived to be the most distinct evidence of the red rock alternating with the lyas: but as this was an important point to ascertain, being at variance with all observations in other places of the position of the lyas and red rock which 1 had heard of, I repeated my examination of the ground with great care, and I think it is probable that the apparently very distinct alternations of the lyas strata with the red rock are deceptions produced by those curvatures and dislocations so common on this coast, as I shall shew when I describe those places. This lyas is an argillaceous limestone of a dull earthy aspect, with a large conchoidal fracture, and generally of a light slate blue colour. It occurs in very regular strata which seldom exceed a foot in thickness, and are often not more than four inches: they are separated from each other by strata of slate clay, varying considerably in thickness. All the strata of this limestone, though externally very similar, are not of the same mineralogical composition, for they have very distinct properties. Some of them yield a lime which possesses in a most eminent degree the property of setting under water: these are generally the thinest strata, are of a light blue colour and compact earthy texture; on each surface of the stratum, and at the joints the colour is changed to a light brownish yellow or cream colour, which is of different thicknesses, in some places extending so far into the interior of the stratum that the blue colour is nearly obliterated. I very rarely found organic remains in these beds.

§ 35. The other variety of the limestone is of a much darker colour, but is most particularly distinguished by the strong fetid smell it gives out when struck by the hammer, and when it is burning in the kilns. It is always in thicker strata than the other variety and abounds in organic remains, it is also very much penetrated by pyrites in many places. These fetid strata have much less the property of setting under water, and are best adapted for agricultural purposes, for which the other are very unfit. The quarries on the spot call the first blue lyas and building lime, the other black lyas and ground lime. They informed me that the building lime always lies above the ground lime, and in a quarry in the parish of St. Decuman's I saw a section where the upper strata were pointed out to me by the workmen as the best building lime, and they find the strata become less adapted for that purpose the lower they go. I found the middle beds slightly fetid, and the lowest more so and increasing in thickness.

§ 36. The fossils which are very numerous in the lyas series in most places, appear to be less abundant here. The cornu ammonis is the most common, and I found it several times above 18 inches in diameter. It frequently occurs in a flattened compressed state with the beautiful iridescence of the nacre preserved; a variety which Mr. Townsend considers peculiar to the lyas of this coast.[7] The following are the few organic remains I had an opportunity of collecting:

Remains of a very finely striated Pecten or Lima.

Remains of a pentacrinite, resembling that which is found on the banks of the Severn, near to Pyrton passage.

Fragment of a large compressed and strongly ribbed ammonite.

Slight remains and traces of some unknown pinnated vegetable converted into coal.

Remains of terebratulæ, much resembling T. lacunosa.

Fragment of a large shell of the genus nautilus.

In several places the surface of the limestone strata is exposed for a considerable way, shewing that in many instances they do not consist of a continuous mass, but of an accumulation of columnar distinct concretions, resembling the Giant's Causeway on the coast of Antrim. These concretions are distinctly separated from each other, all their angles are rounded, and there is no regularity in the number of their sides or their dimensions; in some of the strata the whole surface of each concretion consists of that brown crust mentioned above, enveloping a light blue nucleus. This structure of the limestone makes it very easy to work, as it is only necessary to separate the concretions with an iron bar. In this way a great many of the beds near low water mark are worked, and the concretions are brought in paniers on the backs of little horses and asses to the kilns on the top of the cliff. I observed a similar structure in the red rock, but the divisions were much smaller than in the limestone strata. In both instances the appearance is very like that of amass of dried clay or starch. When the strata of limestone are not divided into those columnar concretions, they are generally separated into large irregular shaped masses by joints perpendicular to the stratification, and in many parts they are penetrated in every possible direction by contemporaneous veins of calcareous spar crossing each other like net. work. They seldom exceed a few inches in thickness, and are in general much more slender; the same vein which in the middle is an inch or two in thickness, gradually thins away at each extremity, sometimes to a hair's breadth, at other times shooting of like a spreading root of delicate fibres. Very often a slender thread cuts across a thick vein, throwing it several inches out of its regular course, affording a miniature representation of the disturbances in the great veins of mining districts. These veins do not penetrate the slate either above or below the stratum of limestone in which they are contained: but there are other veins of calcareous spar which cut through the strata, generally occasioning a dislocation, and in many instances I observed the substance of the vein penetrating the adjoining strata in minute ramifications. It will be difficult to reconcile these appearances to any theory of veins that has yet been proposed; like other instances, which every country affords, they tell us how little we yet know of the laws by which the materials of our globe have been brought together into their present arrangement.

§ 38. The slate clay that is interposed between the strata of limestone assumes different appearances. In some places it is grey, in others brown, and in others nearly black: it is frequently bituminous, having, when broken, a strong fetid smell. The strata are divisible into laminæ as thin as common pasteboard, splitting with the greatest facility, and where it is washed by the sea it is very soft and friable. It appears to contain the same fossils as the limestone, and it is in this that the flattened ammonites are found; those in the limestone preserving their natural form, as far as my observations went. It frequently contains imbedded masses of a limestone identical with that of the regular strata, of a lenticular shape similar in form to the masses of clay-ironstone found in the clay of the coal formations. These are frequently uniform in structure throughout, sometimes they contain slender veins of calcareous spar in their interior, running parallel to their shorter axis but not reaching the surface, and they are sometimes divided into septa which are coated with calcareous spar and sulphate of strontian. I was fortunate enough to break one of those masses which contained this last substance most beautifully crystallized, quite equal to many of the specimens brought from Sicily: the crystals are perfectly transparent and of a pale blue tint. It is not confined to these lenticular shaped masses, for I found it accompanying the calcareous spar of a vein in the quarries near Stringston. Thin strata of a fibrous calcareous spar are frequently found between and parallel to the strata of slate clay and limestone. They are sometimes about three inches thick, and the direction of the fibres is always perpendicular to the plane of the strata.

§ 39. About three miles and a half from the mouth of the Parret and at the termination of the low marsh land, the lyas strata first appear, rising above the sand in a highly inclined position, and nearly covering the low shore between high and low water mark. They are very much covered with sea-weed, and difficult of access from the very deep mud, but their general direction may be traced running between east and west, and dipping in some places to the north and in others to the south. After following this line of bearing a considerable way, they may be seen sweeping round in a great curve, and becoming perpendicular in their direction to the same strata not a furlong distant. They extend about a mile westward from their first rising, and then entirely disappear opposite a tract of marsh land lying between two low bills along the shore for about half a mile: at the western termination of this marsh they again appear in a highly inclined position, and a little farther west the shore begins to be bounded by cliffs, which continue without interruption to Blue Anchor, except at those places where the brooks at Little Stoke and Donniford fall into the sea. From the place where the cliffs begin to that part of the coast which is immediately below Perry Court, they are entirely composed of the lyas strata, and that is the most eastern point where the red rock appears in the cliff.

§ 40. In the whole course of this part of the shore the strata hardly ever preserve a uniform bearing or dip for the space of a quarter of a mile, but are liable to constant changes dipping in every possible direction. It would be impossible, by any description of the particular instances of disturbance, to give an intelligible representation of the extraordinary appearance of this coast on walking over it at low water: I cannot convey a better idea of it than by comparing it to the great waves of a sea suddenly consolidated. These waves are now broken in many directions, and exhibit various sections of their internal structure. That the convolutions took place when the rocks were in a plastic state is highly probable, for the curve is complete, in many cases, without a fracture. Besides these curvatures there are in many places along the cliff and particularly between Shurton Bars and Little Stoke, instances of those slips in the strata which are of such frequent occurrence in the coal districts. Sometimes these slips are only of a few inches, in general they are of a few feet, but they are sometimes so great that in a cliff of 100 feet high there is a complete change in the nature of the strata on each side of the slip; there being on one side of it a numerous alternation of limestone and slate clay strata, and on the other only slate clay with a very few thin beds of limestone. In general I found the line of the slip filled by calcareous spar, sometimes only a few lines in breadth and rarely exceeding a few inches, and in many instances as I have already noticed, I found the matter of the vein penetrating the adjoining rock in slender ramifications. I found some slips where nothing appeared but the line of separation.

§ 41. The lyas formation of this part of the district is bounded on the south by a line commencing at Combwich, and passing through Bondstone and Stringston Church to the point on the coast where I have said the red rock begins, keeping a little to the north of Putsham.[8] The road from Knighton to Shurton Bars crosses a small valley between two hills composed of lyas, and in the bottom of this valley the red rock appears, accompanied as usual by its grey beds. This is one of the places where there is apparently a distinct instance of the red rock alternating with the lyas; for the lyas on each side of the valley and the red rock in the bottom all dip towards the same point. This however is not conclusive, for the actual contact is not seen, and the same source of error which I discovered in another place, and which I shall presently mention, may exist here: the valley stretches in a north-westerly direction and terminates on the shore near Little Stoke. I went to this place expecting to see the alternation more distinctly in the cliff; that however is wholly composed of lyas, but on proceeding along the shore in the same direction I discovered a small portion of the red rock appearing above the sand, with the lyas strata close to it on one side, but whether they lie above or below the red rock it is impossible to say, for they are, within the space of a few yards, both vertical and inclined, and dip to the north and to the south. I observed the red rock in the bottom of another valley between two ridges of lyas, in the road from Benhole farm to Shurton, and here the grey indurated beds contained blue carbonate of copper. As might be expected from the disturbed state of the stratification on the coast, the lyas strata inland rise into ridges; the longitudinal bearing of these is generally from east to west: in the vallies between them patches of red soil often appear, which are no doubt owing to the red rock being subjacent.

§ 42. The northern termination of the Quantock hills descends with so rapid a slope to the sea that I expected to find a section of the grauwacke series exposed in the cliff on the shore, which in this place is above a hundred feet high: there is not however the slightest appearance of them, the whole cliff being composed of the red rock. Where the lyas and the red rock meet, the stratification of both is, in general, much confused, although at a short distance from the junction they are seen in conformable stratification. There are some very distinct instances of regular strata of lyas lying upon regular strata of the red rock, but in all those cases where, if the strata were continued without interruption, the lyas would lie under the red rock, there is always so much disturbance at the junction as to render it very doubtful whether the lyas strata are not turned up or abut against it. The strata of red rock near the junction with the lyas in this part of the cliff are nearly horizontal or dip to the north at a very small angle, but in the western part of the bay they dip south-west, and are covered by conformable strata of lyas; and in this place the grey beds of the red rock are more numerous than in the eastern part of the bay. The lyas strata continue to that part of the coast where Donniford brook falls into the sea. Here there is a kind of delta, formed of a great accumulation of gravel, consisting of pebbles of grauwacke and quartz similar to what is found in the surrounding country. On crossing the brook the cliffs soon begin to rise again, and the lyas strata appear at the bottom covered by about 12 feet of this gravel, which becomes gradually thinner towards the west. The lyas strata continue as far as the headland on the eastern side of Watchet Harbour, and at the place of junction great confusion takes place.

§ 48. It was in this place that walking across the line of bearing of the strata at low water I discovered them in that position which leads me to think that the appearances of the red rock alternating with the lyas may be deceptions. Fig. 1. Pl. 24. is a ground plan of this part of the coast, the dark line representing the cliffs, and the faint lines the strata; a a being the limestone and b b the red rock. I found at A and B strata of lyas dipping towards the same point, and conformably with the dip of the strata of red rock at C. I therefore expected that as in going from A to B, I should cross the prolongation of the strata of red rock from C, although the ends of the strata were not much raised above the sand, I might obtain distinct evidence of the red rock alternating with the lyas: but instead of this I found the strata in the position represented in fig. 2. which is a vertical section in the line A B of fig. 1.

§ 44. The whole of the headland is composed of strata of the red rock, dipping rapidly towards the north in the cliff, but as they extend out to sea they undergo great changes, dipping to every point of the compass and with every variety of inclination. In some places they sweep round, forming a portion of a great circle with the dip of the strata towards the centre, as the lyas strata are seen to do in the eastern part of the coast. Here the grey parts of the red rock, which in general only appear as patches, form regular strata alternating with the red, but at the planes of junction graduating into each other.

Close by the town of Watcher, in the bottom of the bay where the harbour is formed, the lyas strata appear to come from under the red rock, but as usual the junction is obscured by great disturbance. On the western side of the harbour the lyas appears for a very short distance, and abuts against the red rock: at low water the most varied curvatures and dislocations of the strata may be observed. In the red rock eastward of Watchet there are sometimes slender veins of calcareous spar running across the strata, and these, as in the lyas strata, are generally accompanied by a slip.

In this part of the coast the red rock begins to assume a new character, for it contains a large quantity of gypsum which does not appear in it eastward of Watchet.

§ 45. The coast between Watchet and Blue Anchor is composed of the red rock with grey patches, similar to that in the eastern part of the district, of another variety of it containing gypsum, of a blackish indurated clay traversed by gypsum, and of the lyas strata. All these appear in the cliffs and on the shore at different intervals, but the great disturbances in the stratification have thrown the whole into such confusion that I found it impossible during my stay to come to any satisfactory conclusion as to their relative positions. No description without the aid of plans and sections would be intelligible, and these could only be made with accuracy by a residence for some time on the spot. It would amply repay the labour of any geologist who might undertake the task, for the coast abounds with interesting phenomena, and he would probably be able to determine decisively whether the red rock does or does not alternate with the lyas strata. He would at least find abundant proof how very enigmatical the question as to the relative position of strata frequently is; a question of the first importance in geological inquiries.

§ 46. On leaving Watchet, the red rock is for a short distance similar to what is found eastward, but veins of gypsum very soon begin to appear, and they gradually increase in quantity. The rock here is of a bright brick red colour, and very friable; and is traversed in every direction from the top to the bottom by pure white veins of gypsum. Vast blocks of it have fallen down, and are piled above each other and strewed along the shore; in those that are within reach of the dashing of the waves the gypsum is nearly washed out, giving them a very singular appearance. The rock is not distinctly stratified, but the thickest veins of gypsum are parallel to each other, and nearly horizontal: it contains as usual the grey patches and stripes. The principal veins of gypsum are of different thicknesses; in some places they nearly equal three feet, and the red rock between them is penetrated by smaller veins branching off in all directions; but besides these there are other veins which traverse the rest in every possible way. There are also detached masses of gypsum which are surrounded on all sides by the red rock.

There are different varieties of the gypsum; it is in general white, but it is in some places flesh coloured and bright red. There are thick masses of a very pure compact alabaster fit for many purposes in the arts, and there are several fibrous varieties. In some places it is mixed with siliceous sand and small pieces of quartz, and where these parts are washed by the sea, the gypsum is dissolved, and leaves the quartzose parts projecting and very often in beautiful forms. I did not find it in any case crystallized in determinate forms, nor any appearance of its being accompanied by rock salt.

§ 47. Near Blue Anchor the cliff is composed of a blackish grey clay, containing thin beds of a slightly effervescent argillaceous stone, and which appear to graduate insensibly into the clay. These are penetrated in all directions by numerous veins of gypsum, the thickest being parallel with the strata. The same varieties are found here as in the part of the cliff near Watchet, though not so abundantly; and although there is a very great difference in the colour of the gypseous rock near Blue Anchor, and in the mode of penetration of the gypsum, I have little doubt of its belonging to the same formation as the red rock. The strata are very much disturbed, and in one place they form a complete arch dipping south-west and north-east within the space of 50 yards.

All along the bottom of the cliffs where the gypsum is found they are hollowed out by the waves dashing upon them, and where the strata dip towards the sea the upper beds hangover a considerable way in the form of a Chinese roof. Rills of water flow over them in many places, and have worn deep channels. Dr. Maton, in his Tour through the Western Counties, when describing these cliffs, says, that “ the gypsum may be seen concreting under our eyes.” A more attentive examination would have satisfied him that there is only decay, and no production of new matter on this coast.

§ 48. The last appearance of the lyas strata on the shore is about a quarter of a mile westward of Blue Anchor, where there is a low cliff for a short space, not rising above 12 feet. But even in this limited extent the strata exhibit great disturbance. They consist of a yellow clay, containing thin strata of limestone of a cream colour, some slender veins of gypsum, and small, earthy, calcareous concretions. These rest upon strata of the fetid varieties, and underneath these last there an other strata of yellow clay and cream coloured limestone, and in the lowest part of the series I observed in the clay a thin bed of dark coloured limestone full of shells. In this lower yellow clay there is no gypsum.

§ 49. The lyas strata do not extend far inland from the coast. There are here, as in the country to the east, long ridges composed of them, but the surface is very little broken. There are some quarries in the parish of St. Decumans, others near the road from High Bridge to Rydon, and upon the slope of the hill eastward of Donniford.

§ 50. Westward of Minehead, in the lower part of the southern face of North hill, near Venniford, there is found a small insulated patch of the lyas strata. There is a quarry by the side of the road, and it extends in a north-west direction upon the slope of the hill as far as East Lynch, where also there are quarries. It appears to be confined to a space of about half a mile in length, and one-third of a mile in breadth. The strata in the quarry at Venniford dip at an angle of about 30° a little to the west of north: those at East Lynch are horizontal. The occurrence of this detached portion of the lyas strata is very remarkable, being above six miles distant from the last appearance of the lyas at Blue Anchor, and the high ridge of Hayden Down intervenes, which is wholly composed of the grauwacke series.

I should also notice that immediately below the quarries at East Lynch, the rod rock, with grey patches appears in the side of the road. This is, I believe, the most western point where the lyas strata are found in England.

§ 51. About three miles westward of the river Parret, there occurs on the sea-shore one of the most remarkable features of this coast, viz. the remains of a forest considerably below the level of the sea, and now only to be seen at low water.[9]